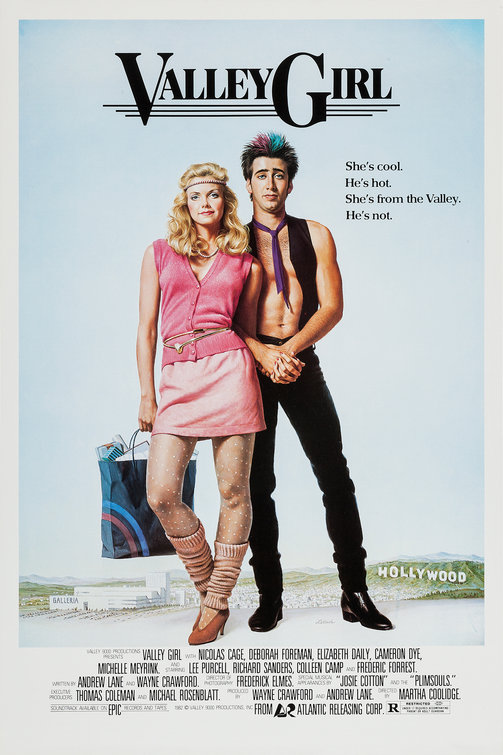

This past week I received a press release informing me that 1983’s Valley Girl would be available on digital platforms for the first time ever! It was a move I’m sure had nothing to do with 2020’s musical Valley Girl remake opening May 8th. Synergy aside, Valley Girl was one of those cult pseudo-classics I’d always meant to revisit.

Happy #NationalGirlfriendsDay! Tag your bestie and let them know you’re thinking of them. #ValleyGirl https://t.co/etx98oU7qT pic.twitter.com/JHCnNUzgc9

— MGM Studios (@MGM_Studios) August 1, 2018

Some Valley Girl points of interest, in brief:

– It was Nicolas Cage’s first big role (after a supporting role as “Brad’s Bud” in Fast Times At Ridgemont High). He played, improbably, a teen heartthrob.

– It seemed to spawn, or at least was part of, the peculiar eighties phenomenon of the “Valley Girl,” despite itself being much less well-remembered than the aforementioned Fast Times. Frank Zappa’s song, “Valley Girl” featuring his daughter Moon Unit doing a nearly unlistenably obnoxious Valspeak monologue, had been released a year early. Zappa actually sued to stop production, that’s how hot the concept was at the time.

– A clip from Valley Girl famously (at least to me) opened The Bouncing Souls’ aptly-titled song, “These Are The Quotes From Our Favorite 80s Movies.”

This was a bit like my generation’s conception of “punk” (The Bouncing Souls) shouting out the previous ones (The Plimsouls, Modern English, The Psychedelic Furs).

One of the things that piqued my interest about Valley Girl is that almost everything in it feels almost impenetrably strange to anyone too young to remember the early 80s. Valspeak. Mall culture. “Punk” music as represented by Modern English’s “Melt With You.” Nic Cage as a sex symbol. High school as a time of freewheeling sexual permissiveness. The entire concept of the “valley girl.” Valley Girl exists almost entirely as a time capsule of extinct and aborted cultural trends.

On top of all that, there was, intrinsic to its plot, the idea that the girl who was from Valley was the cool one. The suburbs being cooler than the city is, again, a bizarro world concept to anyone too young for Valley Girl. But apparently, that was acknowledged as a trope reversal even then. As director Martha Coolidge said in an interview in 2011, “I knew the un-hip image the Valley had for both Hollywood dudes and movie people.”

Was the suburbs-as-setting such an irresistibly novel concept in the eighties that it actually became cool? Between Fast Times, Valley Girl, Back To The Future, Karate Kid, Bill and Ted and basically every John Hughes movie, the suburbs of the San Fernando Valley and Chicago were to eighties teen movies what Seattle was to grunge music. This was the pop culture era produced by the descendants of white flight. These days everything seems to be set in a gentrifying Brooklyn/LA/San Francisco/Oakland.

—

The movie opens (where else?) in a mall — specifically the Sherman Oaks Galleria. The girls are talking about sex and boys and saying words like “grody” and “gnarly” and “totally,” and it all feels very stylized and try-hard. Yet both Coolidge and screenwriters Andrew Lane and Wayne Crawford claim it was meticulously researched. Lane and Crawford said they “hid behind palm trees” at the Galleria to eavesdrop on real teens, and Coolidge said they hung out at Valley schools to get it just right, to the point that Coolidge could argue that the phrase “gag me with a spoon” from the Zappa song was actually an elaboration and that “gag me” was the phrase teens were actually using.

Watching the film, it’s wild to believe that the dialogue was accurate in 1983. The overuse of “like” seems to be the only part of it retained in broader California vernacular, but even there the Valley Girl version seems off. “Like” survives as a bridge word, like “uh” or “um,” but in Valley Girl, characters constantly use it at the beginning of sentences (“Like I’m totally not in love with you anymore, Tommy. It’s so boring!”). Even as a born-and-bred Californian who has been chastised more than once for saying “like” too much, this usage makes no sense to me.

Valley Girl‘s second scene introduces us to Nic Cage and his bizarre chest hair. Cage as the love interest actually makes more sense than you’d think, especially considering the actor cast as his love rival here is best known for playing Buck the rapist in Kill Bill. It’s Cage’s bizarrely well-defined chest patch that’s jarring, much more so than the girls gushing about how cute he looks (Nic Cage actually was reasonably cute in 1983, albeit in an odd, alien baby kind of way). Apparently Coolidge thought Cage’s chest hair made him look too old to play a high schooler, and wanted Cage, who actually was 18 during filming, to shave his chest. This Y-shaped hair island was their bizarre compromise.

It was not especially successful. The reaction it produces is less “yep, that’s a teenager” than “was manicured chest hair a thing in 1983?” Cage, meanwhile, apparently went method for this role, choosing to live in his car in Hollywood at the time, despite how dangerous that was for an 18-year-old Coppola heir in the pre-cell phone era.

In general, the male actors in Valley Girl all look kind of old (Buck was 29) and the moms very young. The actress playing Julie’s mom was only four years older than her screen daughter, and the one playing Beth Brent was only 15 years older than the one playing her daughter, Suzi. Was the “young mom who parties with the kids” another lost cultural comment? See also: “Missy, I mean mom,” from Bill and Ted.

The beach scene leads to the fateful house party, where the actors are dressed in a way that you imagine must’ve been highly stylized. Honestly, if characters showed up looking like this in an 80s-themed period piece in 2020, you’d think the costume designer was overdoing it.

No one even addresses the fact that this guy appears to be wearing a neon ski jacket to a Summer house party:

Yet this was, again, apparently accurate. Many of the actors allegedly even wore their own clothes.

Cage and his “punk” buddy (complete with Teddy Boy haircut) get thrown out of the Valley party before Cage sneaks back in and hides in the shower — the first of many examples of Randy’s stalker-ish behavior. Unable to deny their raw sexual attraction, Julie and Randy eventually kiss, and he takes her to a Hollywood party. They fall in love and share a few more kisses in which Randy creepily cradles Julie’s face with both hands. Influenced by her “shallow” friends (everyone in this is actually pretty shallow), eventually Julie dumps Randy in order to remain popular and goes back to her ex.

Coolidge described the story as a funny take on Romeo and Juliette (which also gave the love interests their names, Julie and Randy). But then, isn’t every teen love story movie basically a take on Romeo and Juliette? Much more noticeable are Valley Girl‘s homages to The Graduate. “I’ve got a little tip for you, Skip,” hot mom Beth Brent says to her daughter’s crush. “Plastics?”

This was either Beth’s veiled reference to condoms or to The Graduate itself — “get it? I’m trying to seduce you just like in that movie.”

Speeches about the emptiness of fashion and the fleeting nature of popularity inevitably ensue, and when Randy kidnaps Julie from the prom at the end of the film, their last shot together in the limo is an obvious homage to Dustin Hoffman and Katharine Ross fleeing their wedding in The Graduate.

It’s one of the film’s repeated attempts to draw parallels between Julie’s Summer of Love hippie parents and her own generation. At such a remove it’s hard to appreciate this much as cultural commentary. But with another step back there is a timelessness to Valley Girl‘s unabashed melodrama. Why bored ’80s mall teens would so identify with bored ’60s bridge party youths seems less important than the simple fact of teens tendency to see themselves as the protagonists of classic love stories. The clothes and music don’t translate, but thinking the question of whether to go out with a punk or a jock is a life-or-death decision does.

Valley Girl, which was intended as a boobs and sun B-movie (Coolidge once said she even had a handshake agreement with the producers that it would include at least four scenes of exposed breasts), ends up being slightly more, thanks to the humanity it affords its characters (who at first glance don’t seem like they warrant it). As Roger Ebert put it in his review at the time, “The teenagers in all those Porky‘s rip-offs seem to be the fantasies of Dirty Old Men, but the kids in Valley Girl could plausibly exist in the San Fernando Valley — or even, I suppose, in the Land Beyond O’Hare.”

If Valley Girl has a legacy beyond the future stardom of Nic Cage, it’s probably that — of female directors taking male producers’ proposed teen sex romps and turning them into sneaky deep slices of teen life. My own generation’s Valley Girl was undoubtedly Clueless, an overtly loud and satirical take on vapid SoCal characters that was quietly a clever and memorable riff on Jane Austen’s Emma, directed by Amy Heckerling (who also directed Fast Times At Ridgemont High).

Valley Girl isn’t quite on Clueless‘s level, but without it Clueless probably wouldn’t exist. In the end, every generation gets the Nic Cage movie it deserves.

‘Valley Girl’ is now streaming on Amazon Prime. Vince Mancini is on Twitter. Read more retrospectives here.