Month: May 2020

When you talk to Josh Trank – which is, of course, over the phone these days – he sounds like he’s in a pretty good place. Yes, by now we all know the trials and tribulations that went into, and came out of, his last film, the ill-fated Fantastic Four. A piece that hit Polygon fills in a lot of the gaps about what Trank has been doing the last few years after Fantastic Four and after his Boba Fett Star Wars film was canceled. But, still, I didn’t know what to expect as far as demeanor. If I’m Trank, I’m probably pretty wary and skittish when it comes to talking with media.

If Trank is wary and skittish, he does a great job of hiding it – bringing up topics I would deem as “touchy” before I even mentioned them. He truly sounds like he’s in “no fucks to give” mode.

Speaking of “no fucks,” Tranks’s new movie, Capone, is quite the thing. It’s remarkable it exists. Tom Hardy stars as famed gangster Al Capone during the last year of his life, hanging out in Florida, slowly dying from syphilis, experiencing fever dream after fever dream after fever dream. Capone is … quite the trip. And then there’s the scene everyone will be talking about, where a halfway lucid Capone is being lectured by law enforcement about some possible hidden money, which ends with a long scene of Capone/Hardy farting and shitting himself.

Ahead, Trank tells us all about that scene, in which Trank even appears as an actor. I asked him about his canceled Boba Fett movie, specifically, when he was writing the script, how did he approach a character that Attack of the Clones painted into such a corner (namely that Fett would have to still look and sound like Temuera Morrison). Also, I asked Trank if he felt any schadenfreude when Dark Phoenix came out to poor reviews, basically in a, “See, isn’t so easy, is it?” way at his former Fantastic Four producer who took over directing duties for Dark Phoenix. It’s obviously something Trank has been thinking about.

But, first, in the aforementioned Polygon piece, Trank mentioned he had a “shit list” of movie journalists. So, yes, I was curious if I was on that list or not.

You mentioned you had a list of movie writers on your shit-list. I don’t want names specifically, but was I on that?

I don’t think so.

Okay.

Well, this was in early 2016 and it had been about six months or whatever since after Fantastic Four came out. The reverberation of the nuclear blast that was the release of that film was sort of, it’s still kind of fresh in my insides and I hadn’t really talked to anybody at all. My whole thing is that, having sort of had my five years in Hollywood circuits in that way after once Chronicle came out, I just noticed that there’s so much politicking that came in this with interviews and with people that I know doing interviews and seeing colleagues doing interviews – in a way that it felt, not nefariously false, but just like more selling of kind of propaganda of just everything being as good as possible when in fact there’s a lot more interesting stuff to say. But, if you have something interesting to say, why peel the curtain back for everybody to realize that we’re just a bunch of crazy people running around trying to stay relevant and figure out what to do next?

Are you talking about something specific? Or just in general?

I’m just talking about in general. Just on anything. I’ve always read books and interviews of everybody – all filmmakers from history that I’ve been interested in – to learn about the reality of this. And I just had always felt that there’s no selling of the reality. Because if you do sell your own reality, there’s a risk of coming across maybe unlikeable, or polarizing, or something. And when he put out the piece, whatever, a few days ago, I had not seen a word of what it was, because I didn’t want to. I read it when everybody else did. So when I got to that part when he had mentioned this shit-list of the bloggers, it wasn’t so much that I had a shit-list. It was that there were particular people, which I would say, extremely off the record, would probably be like [Trank names a movie blogger] or someone like that. We follow each other on Twitter! And we were following each other on Twitter then. And I’m just like, “Bro!” But it’s not you. It was definitely not you.

Okay, I think it will be best to redact that person’s name.

And by the way, if he wanted to interview me now, I don’t hold any grudges about any of that. It makes sense, because the story that was being sold about me was troubling at the time and I can see how everybody would have an opinion. And my memory of what I had gone through was very different than what I was reading about this person and Josh Trank, so it was just very complicated.

And a year after that whole thing, I was still wrestling with my feelings about it, like holding onto being defensive. I felt on some level like betrayed by people who I felt I had done nothing to personally. But, that they had such a strong opinion about how they think I handled the situation professionally, differently than how they would’ve handled it. I just was like, “Yeah, but at the same time, every time you tweet about somebody whose situation you were not there to be a witness to, and who you don’t know in real life, and it’s your verified account on the internet, you’re ruining that person’s credibility.” It seems like nothing to just add to a conversation, but it’s more than that at the end of the day. But I’m glad that I withdrew from that, because it didn’t break me. Ultimately, it made my understanding of things a lot more nuanced in a way that I think has only contributed to what I write, what I work on creatively and the stories that I want to tell. So it really colored my life experience in a way that no college education could’ve ever given me.

In Capone, the scene I think a lot of people are going to be talking about, that you’re actually in, is when Tom Hardy defecates in his pants.

Yeah, he ripped.

Yes.

Yeah, man. It was awesome. It was fun. Because Tom, in real life, is one of my best friends. The thing about Tom – as an actor and from my experience working with him professionally and also outside professionally just on a personal level – is we’re all playful people who have fun with each other. Look, there’s nothing fun about what’s going on at the heart of that scene. And certainly, it’s not about taking a piss out of somebody who can’t control their bowels, because of a physical impairment. But for me to be sitting there in a costume, in a period costume, directly across from Tom Hardy acting in a scene where he’s shitting his pants was, I mean, that’s like top 10 moments. You know?

Right.

He was great. I’m a ham. I know it. And I got to sit there with Neal Brennan and Tom Hardy and Jack Lowden. But we all know each other as people and as human beings. And that’s part of the fun for me; getting to work such incredible world-class talents like Tom Hardy and the entire cast that I had at my disposal to collaborate with, because I get to know them as human beings, and I respect the relatable human being side of people so much more than the myth of who these people are. So for me, it was mainly just sitting with my friends and just doing the scene. You know?

Your Boba Fett movie that didn’t get made, what I’m curious about is, when trying to write a script based on Boba Fett, how much did Attack of the Clones paint you into a corner? I’ve thought about this way more than is healthy for someone not paid to write a script.

The main answer is that, unfortunately, I’ve signed so many NDAs, that legally it would be irresponsible, and I would be liable.

I figured that. That’s why I’m wondering if you can be as vague as possible and still answer that? Because I don’t need specific details, but just how do you approach something where there’s such a constraint on what this thing can be?

Legally, I can’t say anything, but the one thing that’s out there is just that the canon is the canon.

Sure.

The canon that they work with is not including the Dark Horse comics, or any of the books, novelizations, or anything from the video games and any of those plot lines. So, I mean, I think the way that a creative would look at that would be the same way they would look at playing in anybody else’s sandbox. If you’re going to tell a story, you want to sort of distill all the elements of what exists around it into what matters for the story that you’re trying to tell. And I think with any one of those characters that exist in the Star Wars universe or in the Marvel universe, or in the DC universe – or any giant, deeply storied, decades old, century old universe – you could take 5,000 different creatives and they’re all going to have a different idea of what story they want to tell. And I think that’s right in the world of comic book writers.

They all get an opportunity to jump in and take a character from Marvel and create their book out of that character. So I think the best of what’s going on with Star Wars would be something like that. But, you know, I haven’t been involved in any of that since 2015, so it wouldn’t be cool or responsible for me to have any comment on it. I mean, other than the fact that I have deep, deep, deep respect and admiration for all the filmmakers who are involved their currently and have been involved. And that’s not political. It’s just true. It’s absolutely true. I really respect all of them.

I have a hypothetical question. Let’s say, hypothetically, you made a movie that caused some strife in your life. And then there’s a lot of behind the scenes reporting and all this stuff comes out. And the producer you worked with who maybe didn’t always have great things to say, that producer made a movie that got terrible reviews.

Sure. Hypothetically…

Hypothetically, does make that make you want to say, “Hey, not so easy, is it?”

Well, hypothetically, if that happened, and then hypothetically, I at that very moment had received numerous text messages and phone calls from all kinds of hypothetical people that I know, asking me how hypothetically vindicated I would have felt, my answer in real life is not vindicated at all. Because I know he worked hard on that.

When I’ve mentioned many times that I don’t regret anything that happened with any of these things, and I don’t regret having made Fantastic Four and having lost Fantastic Four, and having tweeted about Fantastic Four, I don’t regret any of it. And I don’t have any negative feelings in my heart towards any of the people involved, like Kinberg or Hutch, or Emma… they work really hard. And they care about what they do. They just creatively are interested in things differently than I am, and that’s not their fault, and it’s not my fault. It just wasn’t a good match.

And again, like I said, I’m not interested in giving anybody a political answer about anything. I’m interested in giving answers that come from my heart and are also can be helpful to anybody else who might be going through a situation like that in and out of this business. Because everybody has their Fantastic Four. If you’re an architect, you have your Fantastic Four. If you work as a carpenter, if you work in marketing, or if you work as a journalist, we’ve all had our Fantastic Four.

When you say it’s, “Work with all the wrong people,” the people aren’t wrong. It was just the combination of the people was wrong. It was not a good combination for us to be making something. Whereas me being combined with Tom Hardy and Bron Studios and Linda Cardellini, Matt Dillon, Kyle MacLachlan, Noel Fisher, Al Sapienza, and everybody involved in Capone, that was a good combination. For everything that was wrong about Fantastic Four, everything was right about the experience making Capone. So, when that movie came out, Dark Phoenix, I mean, Simon Kinberg has had tremendous success in his career, and he’s worked on some wonderful movies. He’s worked in this business for a long time. He’s seen a lot of stuff.

I mean, I’m still relatively new in my career. This is my third film. And while that was going on, unfortunately, it didn’t seem to work out, but I was in the middle of working on my movie that couldn’t have worked out even better. And so, there was no schadenfreude or anything like that. I’m too far away from that and I’m too grateful for the fact that the thing that I wrote from my heart after Fantastic Four was something that I was lucky enough to pull together with all of my favorite actors in the world and be able to make it for a budget that allowed me to do it the way that I always dreamed of doing it. I mean, unfortunately, I don’t have any shots fired.

I like how you gave this hypothetical movie a title out of the blue. I don’t know where you even came up with “Dark Phoenix.”

[Laughs] I’m a creative guy.

‘Capone’ will be available via VOD starting Friday, May 15. You can contact Mike Ryan directly on Twitter.

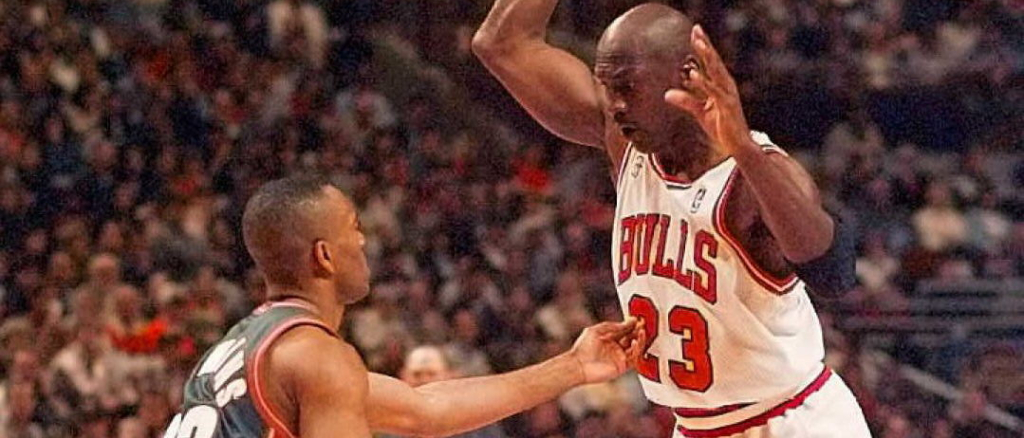

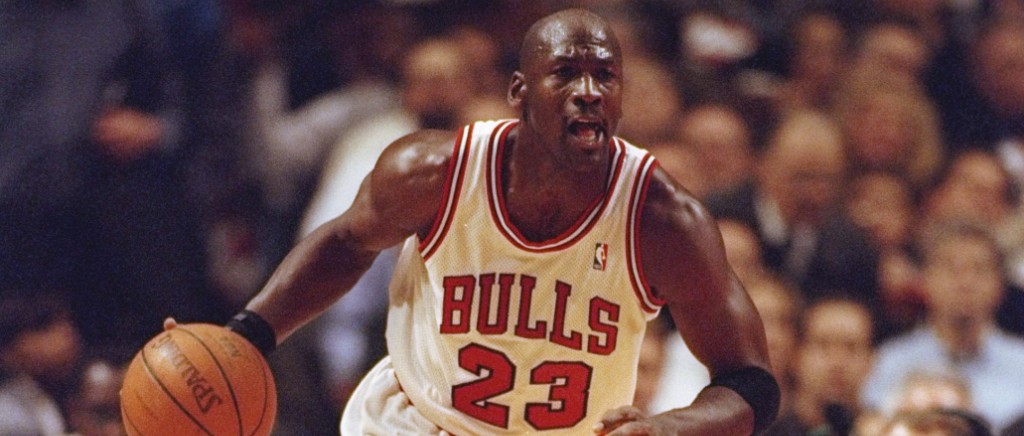

The 1996 NBA Finals pit the Chicago Bulls against the Seattle SuperSonics. While Seattle was a really good team led by Shawn Kemp and Gary Payton, the Bulls had just won 72 games during the regular season and seemed all but assured to win a ring, something that was a game away from confirmation when they went up 3-0 in the Finals.

A major reason why Chicago was one game away from a sweep, of course, was the stellar play of Michael Jordan. Curiously, Sonics coach George Karl decided against putting Gary Payton, perhaps the best perimeter defender in NBA history, on Jordan, telling Payton that he was more valuable as a scorer and that having him guard Jordan would tire him out.

“But we got down 3-0,” Payton recalled during episode eight of The Last Dance. “I was mad. I said, ‘F*ck what you’re talkin’ ‘bout, George, I’m guarding him, whatever you say.’ I said, ‘You can’t control this no more.’”

The move worked, as Jordan had a pair of off nights and Seattle took the next two games in the series, forcing it to move back to Chicago for a Game 6. Payton explained how he guarded Jordan successfully over those two games, and gave a pretty insightful answer.

“A lot of people back down to Mike,” Payton said. “I didn’t. I made it a point, I said just tire him out, tire the f*ck out of him, you just gotta tire him out. And I kept hitting him and banging him and hitting him and banging him, it took a toll on Mike, it took a toll. And then Phil started resting him a little bit, and then the series changed and I wish I could’ve did it earlier, I don’t know if the outcome would’ve been different, but it was a difference with me guarding him and beating him down a little bit.”

The Last Dance is nothing if not a medium through which Michael Jeffrey Jordan can have strong, visceral reactions to things that occurred decades ago. As such, he was shown this clip from Payton and began making silly faces and laughing hysterically before giving a remarkably dismissive response.

Michael Jordan is very entertained by Gary Payton’s breakdown pic.twitter.com/dh7GCEBJCm

— Rob Lopez (@r0bato) May 11, 2020

“The Glove!” Jordan said. “I had no problem with The Glove. I had no problem with Gary Payton. I had a lot of other things on my mind.”

“The Glove” pic.twitter.com/HBmiKGrLqF

— Steve Noah (@Steve_OS) May 11, 2020

Jordan was candid about how it did take a toll on him that this was his first full season and attempt at winning the NBA Finals since his father’s passing. The clip of him cracking up is obviously extremely funny, perhaps the funniest individual moment of the entire series. Having said that, putting Payton on Jordan did lead to his numbers dropping off a bit — MJ averaged 31 points, 5.3 rebounds, five assists, and two steals per game while shooting 46 percent from the field and 50 percent from three in games 1-3. Then, in the ensuing three games, Jordan went for 23.7 points, 5.3 rebounds, and 3.3 assists on 36.7 percent shooting from the field and 11.1 percent shooting from three.

One recurring theme in episode eight of The Last Dance is that Michael Jordan was really good at taking any slight against him — even ones he made up in his head — and turning them into the motivation he needed to destroy opponents. An example of this came prior to the 1996 NBA Finals, which the Chicago Bulls won over the Seattle SuperSonics in six games.

Jordan didn’t really need any extra motivation to win a championship, but a chance encounter with Sonics coach George Karl before Game 1 tipped off certainly helped. As Ahmad Rashad and Jordan recalled, the pair were out to dinner, and Rashad noticed that Karl was on the other side of the same restaurant. When he got up to leave, he decided it was in his best interest to give their table the cold shoulder.

“He walks right past me,” Jordan said. “And I look at Ahmad and I said, ‘Really? Oh so that’s how you’re gonna play it?’”

“He just kinda went by and I went, ‘Uh oh, should’ve never done that,’” Rashad said.

This particularly bugged Jordan, not because Karl was being hyper-competitive, but the two had a relationship even beyond the fact that they were both in the NBA.

“I said it’s a crock of sh*t,” Jordan said. “We went to Carolina, we know Dean Smith, I seen him in the summer, we play golf. You’re gonna do this? Ok, fine. That’s all I needed. That’s all I needed, for him to do that, and it became personal.”

Jordan would go on to average 27.3 points, 5.3 rebounds, 4.2 assists, and 1.7 steals in 42 minutes per game en route to Chicago winning the series and kicking off their second three-peat.

The 1995-96 Chicago Bulls are perhaps the greatest team in basketball history. Michael Jordan’s first full season back in the NBA following his hiatus in Major League Baseball saw Chicago win a then-record 72 games and a championship, kicking off the franchise’s second three-peat. Having said that, while the team won a bunch, there were some major bumps in the road, like the time Michael Jordan punched Steve Kerr during practice.

The story is fairly well-documented right now, but in episode eight of The Last Dance, Kerr and Jordan discussed went into their infamous scrap. As Kerr tells it, Jordan — who spent the previous year working off the rust from his time playing baseball — came into camp in fantastic shape, but he was “frothing at the mouth” following the team’s loss to the Orlando Magic in the postseason the previous year.

Jordan, meanwhile, believed he needed to make his team psychologically tougher, as everyone outside of Scottie Pippen had not spent a full season alongside MJ.

“Steve and Luc [Longley], all those guys, they come in riding high on the three championships we won in ’91 ’92, and they had no f*cking anything to do with it,” Jordan said. “But now they play for the Bulls, but naw dude, we were sh*t when I got there and we elevate to being a championship quality team. There’s certain standards you got to live by. You don’t come pussyfootin’ around. You don’t come in joking and kidding around, you gotta come ready to play.”

In an attempt to control Jordan’s rage a little, Bulls coach Phil Jackson would call touch fouls during practice, hoping it would calm him down. Instead, there was one instance where Jordan snapped, making it a point to foul Kerr hard, to which he turned to Jackson and said “now that’s a f*ckin’ foul.”

Kerr, as one might imagine, wasn’t particularly happy with this. He got up and confronted Jordan by hitting him in the chest, which led to MJ punching Kerr in the face. He stormed off after this, and while he was in the shower, Jordan admits to having remorse because he “just beat up the littlest guy on the f*cking court.”

The two ended up talking afterward, and while this seems counterintuitive, they agree in retrospect that this was something of a bonding moment.

“We talked it out, and in a weird way, it was probably the best thing I ever did was to stand up for myself with him,” Kerr said. “Because he tested everyone he played with and I stood up for myself.”

“He earned my respect,” Jordan said. “He wasn’t willing to back down to be a pawn in this whole process.”

Now, to be 100 percent clear here, Michael Jordan should not have punched Steve Kerr in the eye, because that is extremely not cool. But the pair were able to use it as a way to strengthen their relationship ahead of an historic NBA campaign, so at least they were able to get something positive out of the whole ordeal.

Michael Jordan spent the summer of 1995 in Los Angeles shooting Space Jam, where he worked out a deal with Warner Bros. to ensure he had a facility on the lot that he could work out at. Episode 8 of The Last Dance provided some rare video of the pickup games that featured a who’s who of NBA talent, along with Jordan, B.J. Armstrong, and Reggie Miller’s remembrances of those games.

“I said look, I need to practice, I need a facility where I can work out,” Jordan said. “‘Oh don’t worry about that. We can build you that.’ And sure enough, when we got out there, it was all set up.”

The director of Space Jam called it the “Jordan Dome,” as it was a domed in court with full gym equipment that he used to rebuild his body from a baseball body to a basketball body with trainer Tim Grover. Jordan remembers they would start shooting at 7 a.m. and he’d get a two hour break in the middle of the day where he’d do weights with Grover, then they’d film more until 7 p.m. That’s when those legendary pickup runs would happen.

“After we finished, which was usually around 7, we’d invite people over and we’d play pickup games,” Jordan remembered.

“We had the idea that if we invited the best players in the league out here, we’d get a chance to see everybody before the season started,” said B.J. Armstrong. “And then it became like a thing, everyone had to come out to Warner Bros. studios to play with Michael Jordan. And this was his opportunity to see everybody and we would do scouting reports. This is what Chris Mullin would do. This is what Reggie Miller would do.”

Reggie Miller looks back on those pickup games at the “Jordan Dome” in a similar way Magic Johnson looked back at the Dream Team practices from 1992, while also still in awe at how Jordan was able to film all day and then play late into the night.

“It was some of the best games,” Miller said. “There were no officials, so you were calling your own fouls. So it was a little more rugged and raw. I don’t know how he did it. I don’t know how he had the energy to film all day and then still play three hours. I mean we would play until like 9 or 10 at night and he still had to get weightlifting in and his call time was like at 6 or 7 in the morning. So I don’t know how, this dude was like a vampire for real.”

The footage of those games is pretty cool to see, and for Jordan, bringing in all the best young talent in the NBA — as well as some of his top veteran competition — gave him the added motivation he needed to get back into peak shape.

“Playing against the young talent, they were full of energy and I had to excel my energy and get my talents back,” Jordan recalled.

It’s the most MJ approach to an offseason, non-basketball activity possible, having the movie studio build an entire gym for him to play on and workout in so he didn’t just not lose a step while filming a movie, but actually got better at basketball in the process.

Michael Jordan’s return to the NBA 18 months after his shocking retirement was a momentous occasion. Jordan didn’t play especially well in his return in Indiana, but over the closing stretch of the 1994-95 season he had some incredibly memorable moments — most notably his “Double Nickel” game in Madison Square Garden — all while wearing 45 instead of 23.

While it’s not some long-held secret as to why he came back wearing 45, which he wore as a member of the White Sox organization while playing baseball, Jordan offered an explanation for the decision, with a big reason being his father’s death and him returning to hoops for the first time since.

“I didn’t want to go to 23 because I knew my father wasn’t there to watch me, and I felt it was a new beginning,” Jordan said. “And 45 was my first number when I played in high school.”

In the 1995 playoffs, the Bulls dropped Game 1 to the Orlando Magic, with the most memorable moment being Nick Anderson stealing the ball from Jordan, leading to a fastbreak with Penny Hardaway and Horace Grant, who punctuated an Orlando win with a dunk against his old team. After the game, Nick Anderson famously remarked “45 isn’t 23,” which Grant immediately knew was a bad idea.

For Game 2, Jordan unretired the number 23 and put 45 back on the shelf, going off for a monster 38-point performance to even the series. As he recalls in the documentary, it just wasn’t natural wearing 45.

“It just felt like 45 wasn’t natural,” Jordan said. “I wanted to go back to the feeling I have in 23.”

Given what we’ve learned about Jordan’s constant hunt for motivation from opponents, Anderson’s comments surely helped push him towards breaking 23 back out and proving that, yes, he was still that same guy. Unfortunately for Jordan and the Bulls, they didn’t have quite enough in the gas tank to get past the Magic in that series, losing in six games. Included in that were a pair of losses where Jordan had 40 and 39 points, respectively.

The 45 period of Jordan’s career was short, but memorable, if for no other reason than that number change became synonymous with comebacks.

Michael Jordan had a lot of time on his hands in from late-1994 to early-1995. That period coincided with Jordan’s decision to try his hand at playing baseball, but after his first year in the minors, Major League Baseball experienced a gigantic work stoppage. When the time came for the league to attempt to bring in replacement players, Jordan was steadfast that he would not cross the picket line, and as such, the most fierce competitor in sports had no outlet.

He was, however, in Chicago while the Bulls were going through their season, and as one former Bull tells it, they met up with Jordan and eventually convinced him to come to the practice facility after grabbing a bite to eat.

“One day, he called me and said, ‘Hey, I’m in town, what’re you doing?’” B.J. Armstrong recalled. “I was like, ‘I’m about to go to practice, you know the routine.’ He was like, ‘Let’s meet at Baker Square,’ so I was like, ‘alright.’” After breakfast, we eat, eat our little pancakes and I was like, ‘Well, I gotta go to practice.’ I was like, ‘Why don’t you just come over, say hello, everybody would like to see you.’”

Armstrong’s efforts to get Jordan to visit paid off, and as a result, the retired superstar returned to the gym. At that point, as Armstrong tells it, a sequence of events that sounds a whole lot like Space Jam played out.

“So he comes over to practice and I started telling him, ‘You old, you out of the game, you can’t play no more, I’ll kick your ass right now,’ more or less,” Armstrong said. “First, it was a joke, and then before I knew it, we were playing a full 1-on-1.”

“I just could feel something different was going on that day,” Jud Buechler said. “I mean, it just had a different feeling in that locker room. And I remember asking [Ron Harper], ‘Harp, what’s going on?’ And Harp just turned to me and said, ‘The man is here.’”

Now obviously, Space Jam played out a little differently, but as we all know, the film ends with a collection of NBA players — Charles Barkley, Shawn Bradley, Muggsy Bogues, Patrick Ewing, and Larry Johnson — prodding Jordan into a game of pick-up by telling him that he’s a baseball player who can’t play basketball anymore. This led to a sequence of events that culminated in Jordan’s return to the NBA. A similar situation played out in real life, and while we cannot say definitively whether that inspired any aspect of Space Jam, it sure seems like they followed pretty similar paths.

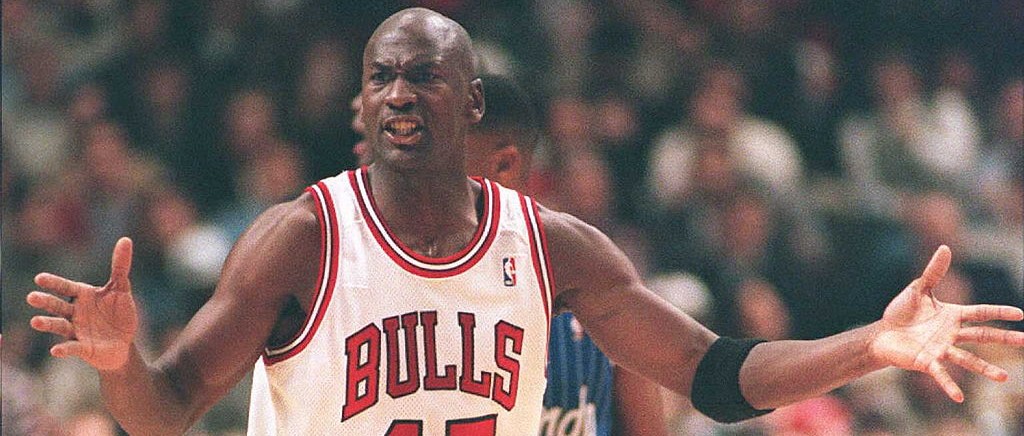

Stories of Michael Jordan’s intense nature and competitive fire, particularly in practice, have become legendary, and the hope when The Last Dance was announced was we would get a chance to see some examples of those with the footage from that season.

To this point, the practice footage of Jordan has been minimal, although the opening episodes did feature him berating Ron Harper for not being aggressive enough, but that changed in Episode 7. It’s the first episode to really dive in to Jordan, the teammate, starting with a section specifically on how he would go after Scott Burrell — a frequent punching bag of Jordan’s this season — and Jordan’s explanation of why he did that.

As the episode went along, he further explained his mentality and why he was so hard on his teammates, with some of those teammates reminiscing on the fear they had and how, while he crossed the line sometimes, what he did worked.

“My mentality was to go out and win, at any cost,” Jordan said. “If you don’t want to live that regimented mentality, then you don’t need to be alongside of me. Cause I’m going to ridicule you until you get on the same level with me, and if you don’t get on the same level, it’s going to be hell for you.”

“People were afraid of him. We were his teammates and we were afraid of him,” Jud Buechler said. “There was just fear. The fear factor of MJ was just so, so thick.”

“Let’s not get it wrong, he was an asshole, he was a jerk, he crossed the line numerous times,” Will Perdue said. “But as time goes on and you think back on what he was actually trying to accomplish, yeah he was a helluva teammate.”

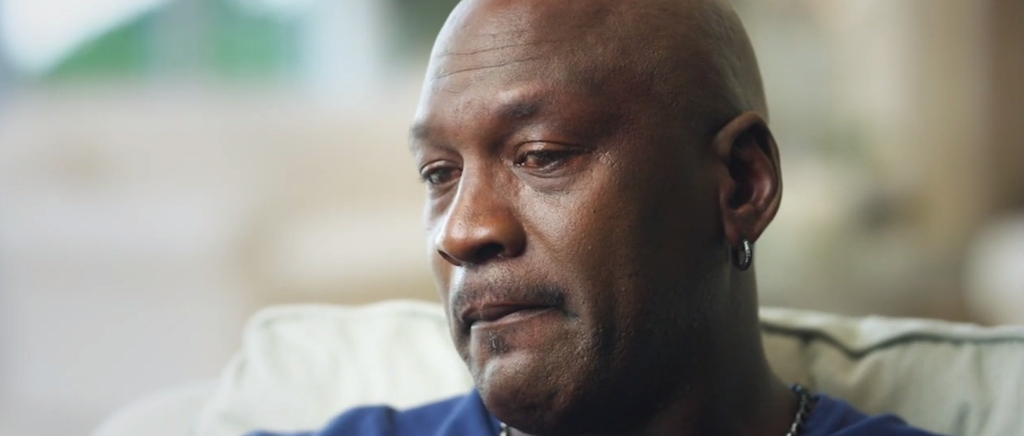

B.J. Armstrong was asked if Mike was nice, and said that Jordan couldn’t really be a nice guy, even if he was “cordial” off the court, because his drive to win was so great and the demands he put on teammates were so high. When prompted on that same question, if his drive hurt his ability to be a nice guy or be perceived as a nice guy, Jordan offered a lengthy quote about the price of winning and how everything he did had that end goal in mind. By the end, was clearly emotional and on the verge of tears, leading to him to call for a “break” from the interview.

The end of Episode 7 … WOW.#TheLastDance pic.twitter.com/N3c5lN0mLI

— SportsCenter (@SportsCenter) May 11, 2020

“Well, I mean, I don’t know,” Jordan said. “I mean, look, winning has a price and leadership has a price. So I pulled people along when they didn’t want to be pulled. I challenged people when they didn’t want to be challenged. And I earned that right because my teammates came after me; didn’t endure all the things that I endured. Once you join the team you lived in a certain standard of how I played the game, and I wasn’t going to take anything less. Now, that means I have to go in there and get in your ass a little bit, then I did that. You ask all my teammates, one thing about Michael Jordan was, he never asked me to do anything that he didn’t f*cking do.

“When people see this, they’re going to say well he wasn’t really a nice guy, he may have been a tyrant,” Jordan continued. “Well, that’s you, because you never won anything. I wanted to win, but I wanted them to win and be a part of that as well. Look, I don’t have to do this. I’m only doing it because it is who I am. That’s how I played the game. That was my mentality. If you don’t want to play that way, don’t play that way. Break.”

It is maybe the best encapsulation of Michael Jordan’s mentality that I can recall ever being captured from the man himself. It’s raw, defiant, and even a bit vulnerable. He clearly doesn’t like the concept of him being a tyrant, but can’t even bring himself to consider that as a valid critique because those that would lob that at him “never won anything.” He’s brought to the verge of tears by the very concept that someone could not want to win as much as him and would be willing to not do everything in their power to tap into their full potential for that goal.

What he says is backed up by what Perdue says as someone who has been punched in the face by Jordan before, but still respects him not just as a player but as “a helluva teammate.” The thing about it all is, there are only a select few that can operate in this way. Jordan was one and Kobe Bryant was another, but you have to be so good and work so hard that when you do verbally berate your teammates or chastise them for what they’re doing, there’s nothing they can do to fire back that you’re being hypocritical. The deification of Jordan has at times led to this idea that his way is the only way to handle teammates, while Kobe’s success with a similar mentality has only furthered that concept. However, they are two incredibly unique examples of the type of person that can get away with that, and when people with lesser abilities or lesser work ethics attempt to emulate them it ends in disaster.