The Punisher may never appear on TV screens again. This might be for the best, considering that the Netflix show developed an identity crisis, perhaps as a response to a premiere pushback due to the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting. Writers attempted to move former Marine Frank Castle beyond his core vigilante function by softening him, which only further muddied the waters of what should be a pretty straightforward comic book character. None of that explains the already wild misappropriation of the antihero’s logo by law enforcement and members of the military. Really though, if one takes the character and contextualizes him against the past five years or so of current events, it’s a solid time to put The Punisher to sleep.

Maybe it’s not time to lose him forever (as some suggested when Netflix’s TV series debuted), but placing Frank, comics and everything, into hibernation mode could be a powerful tool. I’m suggesting that move in light of a growing fan-based movement (amid protests against police brutality) for Disney, which acquired Marvel Entertainment in 2009, to sue police departments that have co-opted the character’s telltale skull logo.

First, let’s run down a few quick examples of cop-and-military fascination with Frank Castle. Those who are sworn to protect us, well, they tend to idolize the guy:

– In 2011, a watchdog report detailed “a gang” of rogue officers (also referring to themselves as the Punishers) within the Milwaukee PD, who (according to their police academy supervisor) “represented a danger that warranted further investigation and action by the department.” The group affixed The Punisher stickers to their gear.

– American Sniper, the 2014 Best Picture Oscar nominee starring Bradley Cooper, is filled to the brim with The Punisher imagery due to Chris Kyle’s fixation with Castle. His platoon went so far as to call themselves the Punishers while painting the logo all over their uniforms and equipment.

– In 2019, the British SAS flat-out told soldiers to stop using The Punisher logo. Officially, the stated reason was that the logo was reminiscent of the “Totenkopf” symbol used by the Nazi SS. Yet the fact remains that there were enough soldiers using the symbol that it needed to be addressed at all.

– Earlier this year, Fox News’ Sean Hannity (who, in recent days, accused Black Lives Matter of starting a militia against police to upend the social order) wore a stars-and-stripes-themed version of the logo as a lapel pin on air.

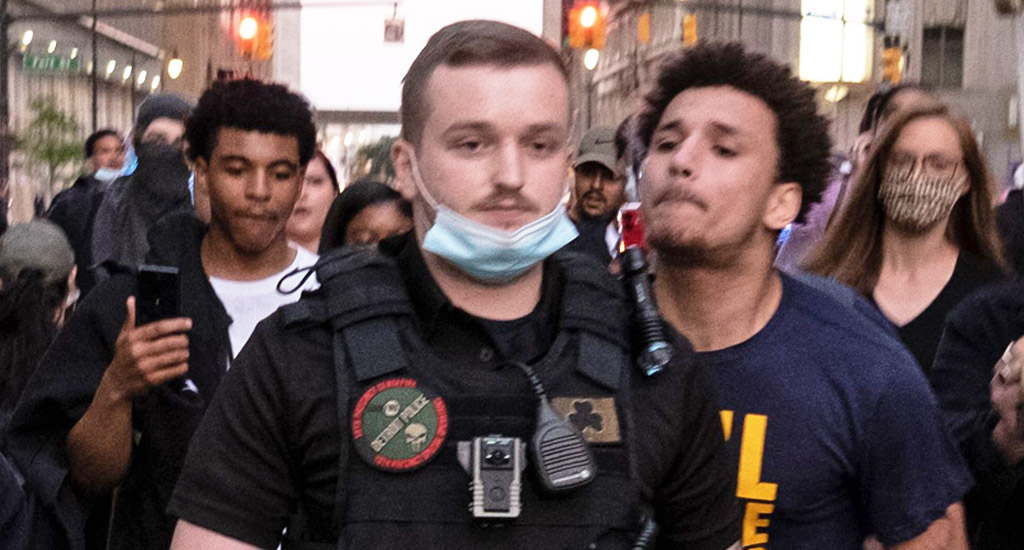

– And last week, Detroit cops were photographed while apparently wearing The Punisher logo on their uniforms while they arrested those who protested police brutality. Here’s an officer walking through a crowd of protesters with a “Detroit Police” patch that includes the skull.

That last example appears to be the last straw for comic book fans, who’ve had enough, but a lawsuit probably isn’t the best way to go here.

These fans are pushing for Disney to sue police departments for twisting the logo’s meaning, which initially makes sense for a few reasons: (1) Disney’s not afraid to put its foot down when it doesn’t want, say, a family to use a Spider-Man logo on a child’s gravestone; (2) Disney has pledged $5 million toward nonprofit organizations (including $2 million for the NAACP) geared towards advancing social justice.

What better way to unite the above two Disney interests than by making a larger gesture (in lawsuit form) against police brutality? Disney doesn’t shy away from lawsuits against copyright and trademark infringement, but there’s a not-so-small issue here: the effort would likely fail, as it did in 2017 when the conglomerate battled a “knock-off business” that “provides unlicensed and poor quality appearances and performances” by actors dressed as “iconic characters for themed events, such as children’s parties.” The argument there, beyond the company profiting from dressing up people as not-Loki and un-Elsa, was that the “shoddy” portrayal of characters, even under different names, was “likely to damage customers’ positive associations with Plaintiffs’ marks.”

Well, a court refused to indulge Disney’s argument, shutting down a summary judgment motion and denying the trademark infringement claim, so the case went nowhere. That’s bad news because such a trademark infringement suit — revolving around defamation, since Disney can’t argue that these PDs are profiting from the logo — would have been the ideal argument against cops using the symbol. Sorry, Marvel fans!

So, where to go from here?

For its part, Marvel has declared (to io9) that it is “taking seriously” any unlicensed usage of its imagery but is sticking with the following statement (also posted to the Disney+ and Star Wars accounts) from last week on their Twitter account.

— Marvel Entertainment (@Marvel) May 31, 2020

Meanwhile, writer Gerry Conway, who brought Frank Castle and his logo (along with John Romita Sr.) to life nearly 50 years ago, continues to speak on the subject. Conway has been vocal for years about Castle’s distaste for cops and military members using the logo for their own ends. Castle is driven by trauma, vengeance, and grief to be a one-man, extrajudicial killing machine who operates outside legal boundaries. Castle can do so because he’s a friggin’ comic book character, not an idol to be emulated.

As Conway explained, police have misinterpreted Castle’s purpose. He actually “represents a failure of the Justice system.” Further, Castle is an indictment of “the collapse of social moral authority and the reality [that] some people can’t depend on institutions like the police or the military to act in a just and capable way.” He simply isn’t written to be a role model for law enforcement or military forces. Last year, The Punisher #13 comic pointedly set out to illustrate this point by including a story of cops fanboy-ing all over Castle, who ripped up their logo-sticker and told them to get lost:

“I’ll say this once. We’re not the same. You took an oath to uphold the law. You help people. I gave all that up a long time ago. You don’t do what I do. Nobody does. You boys need a role model? His name is Captain America, and he’d be happy to have you.”

Here’s the comic book panel of this moment:

When Frank Castle looks like a better hero than cops.pic.twitter.com/z7jxiOBLZM

— Erick Tweets (Trying to sift through reality) (@ErickTweets110) June 4, 2020

Gerry Conway recognizes that the current moment could harness some energy, so he has invited young comic book artists of color to step up for the cause. In a series of tweets, he’s asking artists to help raise funds for Black Lives Matter in a project aimed toward The Punisher. He also noted that this symbol “must *not* be… a symbol of oppression,” and he wants to claim the logo for BLM.

As to the debate over whether the Punisher symbol can ever be a symbol for justice — I agree that’s an open question. What it must *not* be is a symbol of oppression. I want to deny police the use of the symbol by claiming it for BLM. Call it irony.

— Gerry Conway (@gerryconway) June 6, 2020

The question remains, though: would BLM activists even want to repurpose the logo for their cause? It’s difficult to imagine them embracing a symbol that’s worn by cops who are arresting them. Even if Conway could rechannel The Punisher‘s energy for the pursuit of justice with his project, I’d argue that it’s too soon for BLM to associate itself with the logo. A stronger statement would be for Marvel Entertainment to actually shut down The Punisher comic — forgoing those profits for a limited time and asking fans to donate that money to BLM instead. It’s not like Marvel hasn’t done something this drastic before. Remember when they killed Captain America? Steve Rogers was reborn a few years later, and there’s no reason why The Punisher can’t take the same route.

Seriously, put Frank Castle on ice. That would be a powerful stance to take against police brutality, by shutting down their misplaced fanboy-ism. Then get through 2020, and bring the comic back with a Black Lives Matter story arc. Oh, and make a Disney+ limited series to match. People would watch the heck out of that show. Let’s do this.