Classifying Beyonce’s music into a genre is close to impossible — our own Aaron Williams laid out that airtight case already. To an extent, the same goes for her filmmaking, although we don’t yet know what Queen Bey has in store for us with her second visual album, Black Is King. Disney+ will stream the iconic singer’s latest directorial effort on July 31, and it’s probably safe to guess that (once again) Beyonce will deliver the unexpected, whatever that might be, and the project will be a topic of conversation for years to come.

So, we have to hang tight a bit longer, but for now, it’s certainly worth discussing how Beyonce’s status as a filmmaker keeps rising, due to her unwavering resolve to never shy away from her visions for the future. Each of the three Beyonce-helmed films discussed here achieves something different than the preceding installment, and no matter how you feel about her messages in each film, one has to respect that she’s got her reasons, and she’s got her plans. And boy, does she have hustle. Your guess is as good as mine on how she can possibly evolve further past what she’s already achieved through Life Is But A Dream, Lemonade, and Homecoming, but her decisive ambition knows no bounds, so let’s converse about her journey thus far.

Life Is But A Dream (2013): A Cool And Calculated Beginning

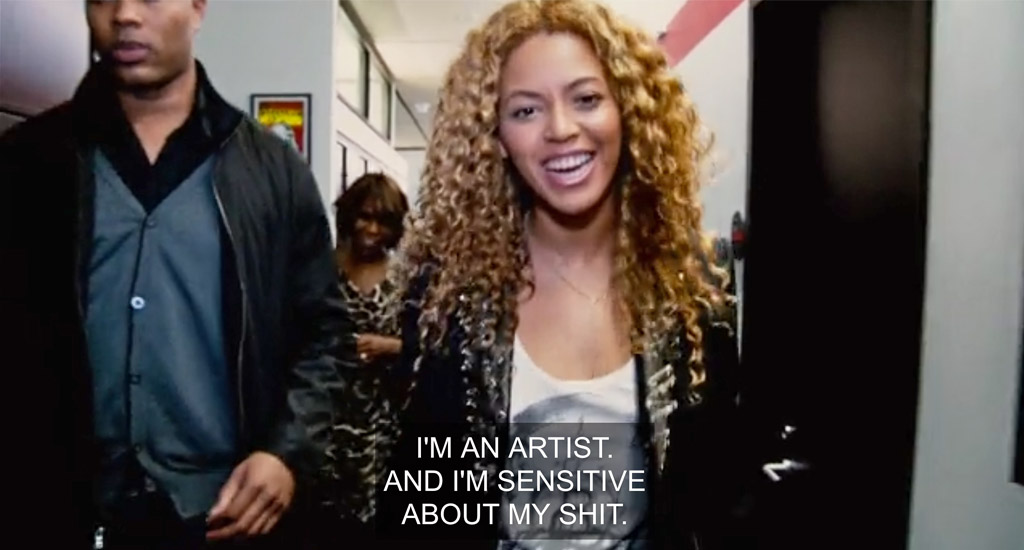

Beyonce went cinéma vérité style for her first directorial effort (which aired on HBO) that chronicles how she stepped out from under her father’s managerial thumb while also moving through the stressful “M”s in her life: marriage, miscarriage, motherhood. On the professional side, the documentary makes absolutely no secret of her artistic prowess and maneuverings, whether she’s practicing dance moves in a hotel hallway or, as shown above, departing a business meeting and declaring to the camera, “I’m an artist. And I’m sensitive about my shit.” She ain’t kidding.

The fascinating thing about Life Is But A Dream (the title comes from an utterance that she makes while on secluded vacation with Jay-Z) is that Beyonce doesn’t even pretend that she’s not the one crafting the “dream.” It’s a creative choice that was criticized when this film came out, given that the end product is clearly calculated to reveal exactly what Beyonce wants to reveal, and no more. And that’s a fair assessment, since this isn’t like Madonna’s Truth Or Dare, where Madge let everything (even her worst moods) hang out in front of the cameras and clashed with her father and other men in her life. Or even like Katy Perry’s Part Of Me documentary, where Katy had no issue being super-personal about her terrible marriage. However, there’s no question that those films’ directors, along with Madonna and Perry, had agendas and perspectives that they wished to push. The same goes for Beyonce, although the lone agenda with this documentary appears to be this: to show the world that she’s the one in control.

Beyonce meticulously plotted out moments that she wanted to portray as vlog entries with stripped down (but still perfectly styled) hair, makeup, and clothing, surrounded by soft lighting. The “candid” footage also doesn’t seem so candid, but as a viewer, I felt like Beyonce knew that we knew that. She hinted very vaguely at feeling pressure and pain over the years but withheld details. She, and only she, is narrator of her own story, and I gotta respect that chutzpah.

Lemonade (2016): Now We’re Getting Cinematic

Now available on iTunes, Beyonce first released this “visual album” as a surprise (in the dead of night) and exclusively via Tidal, the streaming service owned by Jay-Z. Surreal and at times unsettling, the film was actually helmed by seven directors, including Beyonce, given that the project is essentially a seamless assembling of music video clips spanning several themes and styles. However, enlisting others proves that Beyonce does know when to delegate when necessary. As a whole, the film is a substantial piece of artistry and her statement on gender politics and Black identity.

Of particular interest to social media at the time, of course, was how Beyonce also cryptically broached the subject of infidelity. There was the “Becky With The Good Hair” line from the “Sorry” portion (directed by Dikayl Rimmasch), and the “Hold Up” portion (directed by Jonas Akerlund), which produced the project’s most iconic shots. While gliding down the street in now-infamous gold dress, Beyonce let loose in controlled anarchy with a baseball bat, glass and water flying everywhere. Did this portion reflect Beyonce’s personal-life reality in any way? She never clarifies that point, but it was all a testament to how Beyonce can keep an audience on its toes. Whatever her intent, it was a deftly executed one.

Lemonade was a revolutionary approach to album release, for sure, and Beyonce also used the visual album to explore sisterhood, racial tension, and her faith. Years later, that gold dress has come to symbolize her emergence as a well-rounded artist, one who decided not to be afraid to express anguish and pain within a much larger project, which covers expansive themes that tie the individual to the whole of society.

Homecoming (2019): A Fully-Formed Vision Emerges

It’s one thing shoot portions of a film and then get what many consider to be the “real work” done (to effectively hammer home intended messages) in the editing room. It’s quite another thing to communicate one’s specific vision to hundreds of onstage performers, make it all work at the historic “Beychella” performance — the first time that a Black woman headlined the festival — and also helm a movie that filters those messages to the screen. Once again, Beyonce gave us a documentary unlike the rest, even including Life Is But A Dream, that preceded it.

Beyonce meant business, both literally and figuratively, and the footage shows how she meticulously fine-tuned every aspect of the set by collaborating with an enormous team and overseeing multiple rehearsal soundstages. She did not hesitate to push harder to communicate her vision of Black cultural legacy while gathering an unparalleled entourage of musicians (brass and orchestra), dancers, and costumes that paid homage to historically Black U.S. colleges (and their Greek organizations, as with the Beta Delta Kappa sweatshirt detail), an Egyptian queen, and the Black Panthers. References to Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, and Audre Lorde resonated, as did the inclusion of the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

Likewise, the documentary itself was a meticulously constructed homage to Black power that traces Beyonce’s entire process, from her beginning inception of the concept all the way to launching a full-on cultural movement. With Homecoming, Beyonce didn’t simply stick with being the one to call the shots. She became the maker of her own myth, one cemented by an unyielding vision of Black feminist politics. Her vast Homecoming accomplishments are breathtaking. I’m more than ready to see what she’s got in store for us with Black Is King.

Disney+’s ‘Black Is King’ streams on July 31.