In trying to write about Caddyshack this past week I fell deep down a rabbit hole I’m only now clawing my way out of. Stories about the making of movies usually aren’t that interesting, but this one sends you in all different directions. Chevy? Bill? Douglas Kenney? The National Lampoon? When you try to pin it down you start to understand why the initial rough cut was four hours long.

But let’s focus. In the midst of all those rising stars and eventual comedy icons there was Michael O’Keefe, playing Caddyshack‘s presumptive protagonist, Danny Noonan. He’d lied his way into the starring role (telling producers he was a scratch golfer) beating out his rival, Mickey Rourke. It fit, because, like the Murray brothers (Brian Doyle and Bill) on whose childhood Caddyshack‘s story was based, O’Keefe had grown up in a huge Irish-Catholic family working as a caddy.

Everything got pretty weird after that. O’Keefe, who was nominated for an Oscar in The Great Santini, which he’d done just before he got the Caddyshack gig, arrived to a cocaine-besotted set in Florida (Florida in 1979: enough said) where the first-time director (Harold Ramis) had thrown out the script and let his cast go wild. The coming-of-age tale he’d signed on for had become… well, whatever the hell Caddyshack is. A slobs-vs-snobs story, sort of.

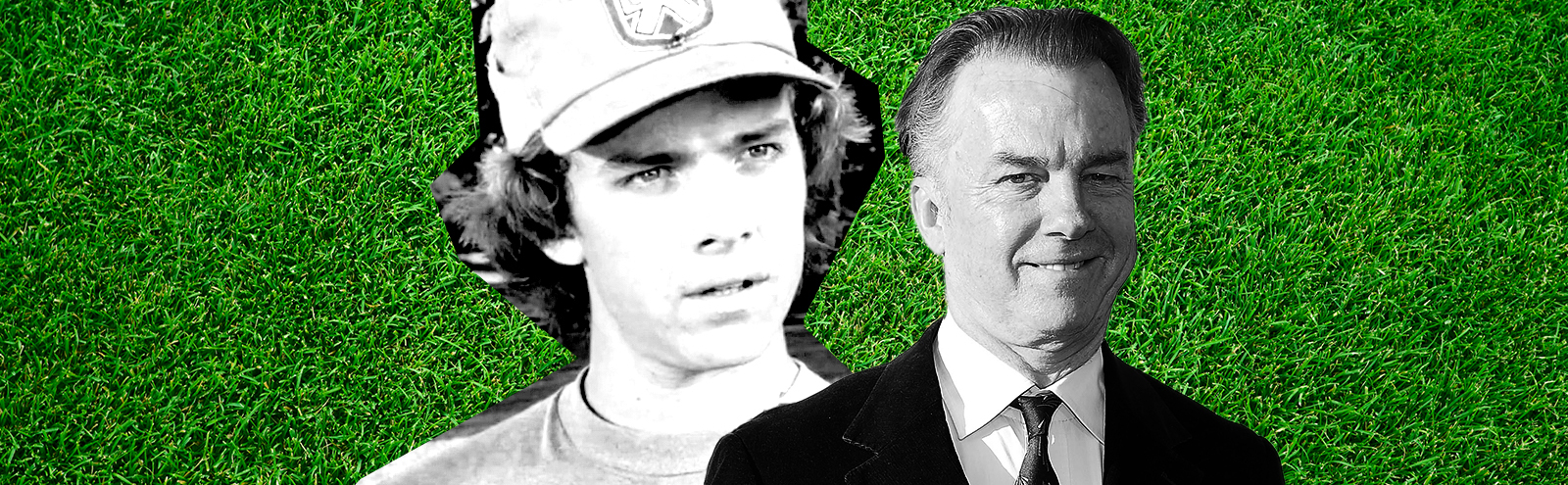

A wild time was had, the likes of which would never be seen again. O’Keefe would get sober (an alternative preferable to Caddyshack writer Doug Kenney, who died three months after release, in a slightly mysterious hiking accident in Hawaii), and go on to have a fine career. He’s 65 now and, minus a few lines, looks pretty much the same as he did 40 years ago, with an admirable head of hair. Somewhere along the line, he married and divorced Bonnie Raitt and was ordained as a Buddhist priest. I told you, it’s a rabbit hole.

O’Keefe was gracious enough to reminisce about Caddyshack and reflect on its legacy this week, though as he puts it, if you can remember the set of Caddyshack, you weren’t really there.

—

So take me back to the time when you got the part, what was going on in your life at the time?

I did a meeting in New York with Harold Ramis and then they called me back in LA and I saw Harold and Doug [Kenney] and Brian Doyle-Murray. And I had already done The Great Santini and that was with Orion, which was the same distribution company as Caddyshack. You’ve probably heard this story, but according to Wallis Nicita, who was the casting director, it came down to me and Mickey Rourke for the part. I could spend days musing on the possibilities of Mickey Rourke as Danny Noonan, putting down his bag to go perform a hit at lunch and then coming back.

I heard it had something to do with your golf game.

Well, I frankly lied at the audition and told them that I was a competent golfer and I was hardly that. I was terrible. I played a little bit as an adolescent and probably hadn’t played since I was 12 or 13, which was like a 12-year window. So, I mean, I had to really start from the ground up. I had about a six-week window where I could prepare and I got hooked back into the Winged Foot Golf Club, which is in Mamaroneck [Long Island] and is a golf club that I caddied at when I was a teenager. And then when I was in Florida, I worked with the Toski brothers and they’re kind of a legendary golf-teaching family in Florida. So, whenever I wasn’t working on camera, I was hitting golf balls. It got me to a point where, as Ben Hogan used to say about a lot of his shots, my swing was serviceable.

To me, you look like clearly the most competent golfer of the people that were playing in the movie.

That would have been an easy thing to look like! No disrespect meant, but nobody in the movie had a good… the real golfer in the movie is Bill Murray. But, of course, he didn’t play golf in the movie. He’s a far better golfer than I’ll ever be.

Do you still play at all?

No, not really. I’m married and I have a seven-year-old son and a lot of my free time is devoted to that. And also I’m really into Tai Chi and qi gong, and so the time that I would have to practice golf, I’m usually doing that. There was a window there though for about 10 years before I got married where I played a lot, and I got down to about a 12 handicap when I was playing.

Now that you’re into Tai Chi and I think I read you were a Buddhist… uh, something or other…

Yeah, I’m a Buddhist something or other, Vince. That’s the official title.

I didn’t want to mess it up. I think the book I was reading said you’re a Buddhist priest, but then I was thinking, “Wait, that doesn’t sound right.”

I started in 1985 when I was 30 years old and the teacher I was studying with at the time is a guy named Bernie Glassman. He started an order of priests called the Zen Peacemakers. We do something called “engaged Buddhism,” which means we practice a certain kind of social action. We get up off the cushion. So he started this order called the Zen Peacemakers and I did ordain in that order in 1994, I believe.

With all this in your background, it seems like you could actually live out, as Danny Noonan, all of Ty’s [Chevy Chase’s character’s] advice in the movie, to get spiritually connected with your golf game.

Well, one of the people who really influenced me early on about Zen was Doug Kenney. Doug was one of the people that turned me on to Zen in the Art of Archery, the Eugen Herrigel book, he was German author that wrote the book in 1927, I think. And for all of Doug’s kind of insane fake Zen poetry, you know “a flute without a hole is not a flute, but a donut without a hole is a Danish,” and stuff like that, he actually knew a lot about it. He was one of the people that planted the seed. But I suppose if I’m like anybody in the film, it’s Ty Webb, without the golf game.

What did you think when you saw the movie for the first time, did it turn out a lot differently than what you thought you’d shot and what they’d pitched it as?

Well, the script was changed, I’m sure you heard the story, about nine or 10 days in. Harold and Doug and Brian realized that they had this potential modern day Marx Brothers combination of Bill and Chevy and Ted and Rodney. And so they began to cut a lot of the Danny Noonan stuff to focus on them. I’ve said this before in interviews and it was true for me then and it’s true for me now, I was kind of relieved because they are in a different league than I am. I have a lot of skills as an actor and I had a certain amount of skills when I was younger, but Bill, especially Chevy, Ted, Rodney, were all just in a different playing field than I was. And so to turn things over to them was something of a relief because then you have all those speeches that Bill wrote about the Dalai Lama or winning the Masters. And Rodney’s incredibly off the cuff, crazy Catskills humor and then Chevy’s work as well and Ted too. Ted was the ultimate professional. He was really the one who kind of held the ship together, because he had the ethos and the ethic of trying to be a responsible adult, whereas everybody else was doing their best to be an irresponsible and immature adult.

It sounds like the set was a pretty crazy time. How do you remember it?

Well, as David Grosby often said about the ’60s, if you say you remember the making of Caddyshack, you weren’t there. These are all things everybody knows now, but I’m still somewhat mortified to talk about them. There was cocaine everywhere. We were all getting high. There was a kind of mythology at the time that somehow this led to more creative experiences. That’s a rabbit hole that a lot of people never came back out of and directly connected to Caddyshack in that regard. That’s how Doug Kenney died. So while there’s a lot of goofy stories, which are really fun and we had a great time while we were doing it, there’s a whole serious downside, which I make sure to talk about when I talk about the film, because I don’t want anybody to get the idea that you can get away with that kind of stuff, because you can’t.

Is that still the wildest set that you’ve been on?

Well, yeah, because it was the ’70s and I also got sober after that. It certainly was the last time I did cocaine. And also all of that stuff just became a liability. You can’t get insured with all those issues now. And most associate it with drug addiction and people going to rehab and people blowing up their career by doing some stupid thing under the influence of drugs or alcohol, it’s such a big deal now, that set could never happen. And it was very clear after we did that that it shouldn’t happen. I mean, it was really just insane. But at the time, look, if you go back and read the stories about the making of Lenny Bruce or the making of The Gambler with James Caan, that’s what everybody was doing. Go back and look at the making of New York, New York with Scorsese and DeNiro and Liza Minnelli. But now you’re a pariah if you do anything like that.

Did Doug Kenney dying have anything to do with you getting sober?

Absolutely. Scared the shit out of me. And frankly, I loved him. Have you had a chance to see A Futile and Stupid Gesture yet, on Netflix? First of all, it’s a good movie. Will Forte is great. Martin Mull is great. And these two young writers, I was the first person they approached only because they were staff writers on Leverage, the Timothy Hutton show that I was on for a while. And I did an episode of it and I went to a screening and they came up to me and they were like kids in a candy shop. They were Caddyshack fans. They were like, “We really want to write this movie about Doug Kenney.”

And in the back of my mind, of course, being the cynic that I am, I was like, “That’ll never happen.” Ten years later, they got it done. And my hat’s off to them because I know how hard it is to get a movie made. They were really diligent. They talked to everybody, but they also wrote a really effective look at Doug’s mindset and how he got into the zeitgeist at the time and how he really led. I loved Doug. Everybody did. He just inspired this kind of affection and loyalty and friendship in people, and people were just crushed when he died,. And so one of the things that happened to me, I was like, “I am never going back to that kind of scene again.” And I never have.

So you were basically doing the Murray Brothers’ life story in a way. Did they coach you at all on playing this character that was so close to their childhood?

They didn’t need to because I’m the oldest of seven from an Irish Catholic family too. So we could probably tell stories to each other and forget whose family we were talking about. The real job was to connect with Chevy, especially, and Ted, and then kind of let them lead the way so that this kind of slobs-versus-snobs thing that Harold and Doug had refined on Animal House.

So you have seven siblings, how did you first get into acting? Because you started pretty young, right?

I was dropped as a child, Vince, that started it all. No, we grew up in this really big house in Larchmont, New York, near the city. We moved into it when I was about 12 and the prior owners had rented it out for commercial locations. The location manager came to the house one day and knocked on the door, cold-calling and asked my mother if she would rent us the house. And she was like, “…are you going to pay us?” And he said, “Yeah.” And she said, “Done.” And then it was seven of us, kind of blonde, good looking kids hanging out. A number of us were there that day when he came by, I remember the day, and he said to her, “Your kids are actually kind of good looking and they could probably model and I represent actors. Would you be interested in doing that?” And my mom said “…would you pay them?” And he said, “Yeah.” And she said, “Done.”

And then very quickly, most of my brothers and sisters lost interest, but I was always on a mission, even at the age of 12. And by the time I was 15, I was taking acting classes in the city. I was at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. And I did a showcase play there that both Peter Weller and Melanie Mayron were in at the time when they were young actors. And so I got an agent after that and then I just started working. I dropped out of college my first semester. I was a terrible, terrible student, but I had this passion about acting and I got an offer to do a play at the public theater with Barbara Barrie, who is one of the most wonderful actors you’ll ever meet. And Ralph Waite, who was playing the father on The Waltons at the time. So anyway then I just kept going and never looked back and I’m kind of pleased to turn around now at the age of 65 and say, “Oh yeah, well, that all worked out.”

You were in The Great Santini and it hadn’t come out yet, and you got nominated for an Oscar before Caddyshack had come out. And then you’re in Caddyshack, which is this sort of whatsit at the time. What do you think Caddyshack did for your career at that time?

Well, at the time the film was not very successful, so nothing. Now what’s happened is there’s this kind of a crude benevolence, I want to say adoration, but it sounds a bit much. But there’s something about Caddyshack that sparks the affection of the American filmgoing public. I got tagged in it and I went to a Comic-Con last year and Chevy and I, and Cindy Morgan were there and we signed autographs and people cannot stop talking about that movie, and it’s 40 years later. Who knew at the time? I mean, part of the dilemma Doug was facing, besides the fact that he was strung out on cocaine and clinically depressed, was that he did not like the final cut of the movie at all. He had really intended what they’d call in lit classes, a “bildungsroman,” and it was anything but that. It was this weird kind of pastiche of standup and improv and Bill and Chevy kind of in one style and Ted in another and Rodney over here. I think it all kind of melded, but for Doug he was really not happy.

I probably came out somewhere in between. I did things as an actor where I was clearly uncomfortable and not happy with myself, and I didn’t have the ease and aplomb that you get over time. But I was very happy with my golf swing, I was really happy with the stuff with Chevy and with Ted. And now, it’s like I could say whatever I wanted to in a critical way about Caddyshack, it would fall on deaf ears.

Are there any other good memories from shooting the movie that stick out in your mind?

Mainly watching Bill come up with all those monologues. I happened to be there when he came up with the, “Young greenskeeper, Cinderella story. He’s got about 320 yards to the hole, he’s going to punch an 8 iron.” I was sort of walking by and Harold grabbed me and said, “Oh, you got to watch this. It’s great.”

Harold, he would say to Bill, “You know that thing where you’re a kid and you’re playing basketball and you’re in the NBA final and you have two seconds left, and–” and Bill would say, “Don’t say anything else.” Then he would go out in front of the camera and just start. He did that on the whole Dalai Lama speech on the fly too. It was amazing.

And getting to know Rodney, who was the most genuinely kind of nerdy, sweet, kind guy. If you talked to any standup comedian from that era that went through Rodney’s club in New York, they’ll tell you how much he worked for other comedians and how much he helped them. I remember we ran into him just before he died, and he had had open-heart surgery. There was this place, it’s not there anymore, but in LA, Kate Mantilini, on Wilshire Boulevard and Highland. It was an industry place. I went in there to have lunch one day and this was probably already in the 2000s just before Rodney died. There was Rodney with his wife at a table and he was wearing one of those matching summer outfits that you see Miami elderly people wear, with a really horrifying pattern where the shirt matched the shorts. And the shirt was completely unbuttoned, and he had a scar from his throat to his belly button and it’s wide open. And I was like, “Rodney, it’s Michael O’Keefe.” He goes, “Oh, hey kid, how you doing?” I’m like, “Rodney, you look good.” And he turns to his wife, he goes, “You hear that, baby? I look good.” He was so endearing.

What do you miss most about comedies from that era? Are there things they were doing at that time that maybe forgotten about or that we’re not doing as much anymore?

Well, I mean, I don’t know that I miss anything from that era because there’s stuff out there now that’s got parody. I think anything Will Ferrell or Adam McKay did has elements of genius in it that are off the chart. I’m sure Judd Apatow learned a lot from all of that and went to school on that film. Also, my wife and I just watched The Great, which is this series with Elle Fanning and Nicholas Hoult, which is hilarious. So there’s no dearth of good comedy out there. But those guys shifted the table. Because if you go back and look at the straighter ’60s comedies, like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World or any of the Rock Hudson, Doris Day things, they were just a little stiffer. It’s not to say they weren’t funny, but you know who was really cutting edge way before Caddyshack, when you go back and look at his career? Alan Arkin. If you go back and look at The Russians Are Coming or Catch 22. So certainly Alan Arkin was way ahead of the curve on all that stuff. But there wasn’t that kind of rebellious tone really except in Robert Altman’s work. If you go back and look at Robert Altman’s MASH, because I bet you dollars to donuts, that was a big, important film for Doug Kenney.

So what are you working on now?

I’m doing this thing with Kevin Bacon, City on a Hill, which I’m hoping will boot back up again. I got shut down right in the middle of the second episode of the season. It’s the second year on Showtime. It’s really a great show. I did a feature for Netflix that Bob Pulcini and Shari Berman directed. They’re the ones that did American Splendor, the thing about Harvey Pekar. This is with Amanda Seyfried and James Norton. And I got teamed back up with Karen Allen as husband and wife. And they had cast us without knowing that we had done a picture in 1980, right after Caddyshack in which we at later became boyfriend and girlfriend after. So that was fun. And then I did this thing with Adam McKay and John C. Reilly about the purchase of the Lakers. Reilly plays Jerry Buss and I played Jack Kent Cooke, the guy who sold them the Lakers. And then it’s really about the acquisition of Magic coming to the Lakers. And so that’s a Showtime pilot that I had been into. That was amazing.

‘Caddyshack’ turned 40 on July 25th, 2020. Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can read his ‘Caddyshack’ 40th anniversary retrospective any day now.