“I think what we’re trying to do when we’re living out loud with our fashion is we’re trying to differentiate ourselves. We’re communicating who we are through what we have on us. Having something that is handmade or that has had a lot of work put into it, you can feel that in the garment. It’s heavier, more substantial, it feels richer and nicer.”

Art and authenticity still mean something to Emma McKee. The Chicago-based artist and designer — more popularly known as “Stich Gawd” thanks to her skill at crafting elaborate hand-made cross-stitch jackets — cares far more about quality than commerce. In a world where Warhol and Basquiat prints are slapped on t-shirts ad nauseam, little feels sacred. But for McKee, once money enters the conversation the purity of the craft begins to feel diluted.

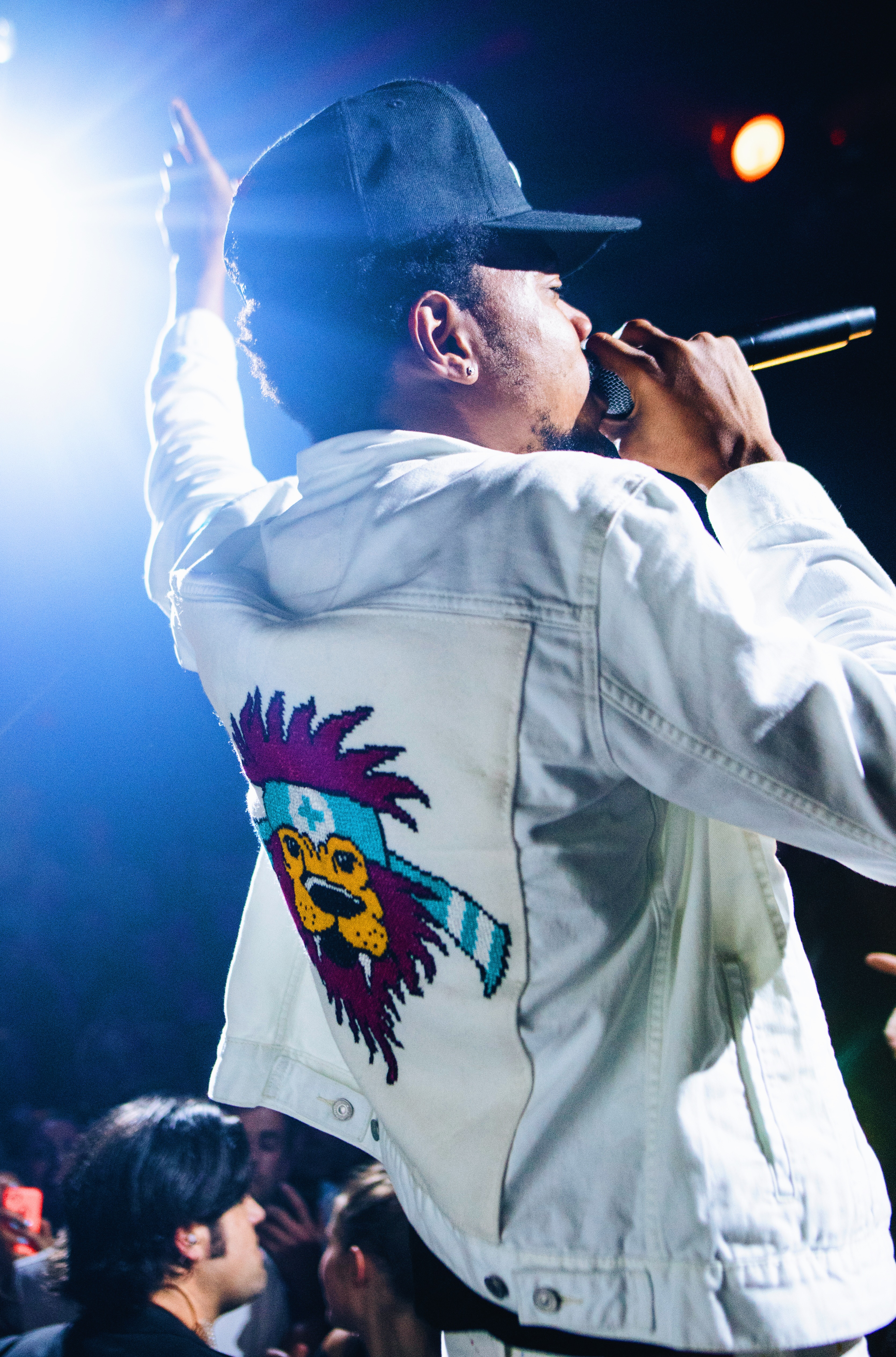

This helps explain why the artist — who has cross-stitched jackets for stars like Chance the Rapper, Saba, Vic Mensa, Katrina Tarzian, Joey Purp, and Lil Yachty — won’t accept cash for her pieces. Instead, she prefers to trade her craft for a specified amount of a certain artist’s time.

“There is so much worth that we forget about people because we’re looking at the bottom line of things,” McKee told me recently while readying her latest project, a nine-foot-tall portrait of Civil Right’s leader Fred Hampton to be shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.

The Stitch Gawd, who was born in Kansas City but calls Chicago home, puts a special emphasis on rappers from the Windy City — where her career as hip-hop’s go-to cross-stitcher catapulted her to international fame. She lives and breathes the local scene, a firmly planted fixtured in the local rap community, and to be “blessed by Stitch Gawd” is now an important rite of passage for young Chi rapper’s on the move.

If you’re rocking a cross-stitched jacket by Stitch Gawd, you’ve just about made it. The future is looking bright.

We linked up with the artist to talk about why the hell cross-stitching — aka your grandma’s favorite hobby — is resonating so strongly in the hip-hop scene, how she approaches her design process, and what she hopes to see change in the ever-shifting realm of streetwear.

How did you first get into cross-stitching?

Totally unwillingly! I’m half British, so everyone in my family cross-stitched except for me because I thought it was tedious and awful. A couple of years back I wanted to get my mom something really nice for Christmas but didn’t know what to get her, so I thought “well she’s been trying to get me to cross-stitch my whole life, let me try to whip something up for her,” so I taught myself how to do it and it came super naturally, like super duper naturally, and I thought “oh, wow I’m really good at this.”

I started wondering if I could start doing it in a less traditional way and try to make my own stuff and I did!

Cross-stitching is a very traditional craft, why did it make sense to you to filter the practice through pop culture themes?

At the end of the day, cross-stitch is just a medium right? If someone tells you they paint, you don’t just assume they do trees, or they’re an impressionist or whatever. Cross-stitch is this weird medium where the medium dictates the content, which doesn’t make much sense to me.

I wasn’t trying to do something really crazy or different, I just had all these ideas, and the one method of expression I had at my disposable that I was good at was cross-stitch.

What do you think it is about cross-stitching that seems to be resonating in the hip-hop and streetwear community in particular?

That’s an interesting question because you wouldn’t think the two would naturally go hand in hand. When you see it in person and you’re holding it, it just looks like there is so much work involved, it looks so different than anything else. I think for hip-hop or streetwear in general, any situation that makes someone think “oh shit, that looks different” is going to be a thing. Finding new avenues in streetwear and pop culture is always going to catch someone’s attention.

As far as embroidery goes, cross-stitch itself looks so different than any other form of embroidery. You don’t see it in very many pop culture arenas. I think the closest you get to see it is in some ironic Little Jon lyric cross-stitched in an episode of Girls or some shit, you usually only see cross-stitch being used ironically and I just think that irony is so played out.

Who gave you the Stich Gawd name?

The first piece of press I ever did was for The Fader and the girl interviewing me called me that jokingly and it super stuck! How crazy is that, no one knows what you’re doing, and all of a sudden the first piece of press you get, it’s like being knighted — they dub you with this crazy nickname and now peopled don’t even know my real name anymore.

They act like my first name is Stich and my last name is Gawd.

You’ve made some jackets for some of the biggest artists in hip-hop, have you been particularly starstruck by anyone?

Kanye…I was very very starstruck by Kanye, but he’s so larger than life how could you not be?. Chicago is kind of a funny place, everything is just so small. Chicago people never really made me starstruck because I’m always much more impressed.

Everybody else I’m just impressed to meet, I know their work very well, and I’ve been working on stuff for them, it’s like meeting an old friend.

Do you have a favorite piece you’ve made for someone, or is it too hard to pick a favorite?

Oh no, I have a favorite! You think that would be hard, but this is why I can’t have kids — I’d definitely pick a favorite, it wouldn’t be fair!

My favorite piece is this Long Live John Walt jacket. There is this rapper, Saba, he’s from Chicago, one of my favorite rappers of all time. I made him a piece early on, but wanted to make him something else, but what to make him totally eluded me. That’s super frustrating when you really want to make something for someone but you can’t think of what the idea is, and for everybody else, it just came so easy, but for Saba… I couldn’t.

Then this crazy tragic thing happens, his cousin was murdered at 3:00 in the afternoon, two weeks before Saba is going on his first national sold-out tour, and its the same weekend Chance is winning his three Grammys, so we were all out in LA doing that, and we hear John Walt was murdered.

So I decided I would make Saba some armor to take with him on tour. I wanted to make a portrait of his cousin so that Walt could come on tour with him. It was down to the wire, I was working on it until 1:00 in the morning, he was going to O’Hare airport at 3:00, I drove out to the Westside to drop it off.

I had never done a portrait or a memorial jacket like that, it has always been things I’ve given people, but this one… he said he felt protected in it, and that just took the wind out of me. Making a piece of art that can be in any way meaningful to a person like that, just makes my head spin.

I saw this whole different power in the medium that I didn’t really see before — to help someone. So that one really turned the corner for me in terms of how I do things, how I think about the work, how I work with people. It really changed a lot for me. It’s my all-time favorite. But my second favorite piece would have to be a new piece inspired by that one, I’m doing a 9 foot 200-pound portrait of Chairman Fred Hampton, that would be my most recent favorite piece.

So in terms of your favorite, it’s less about the technical aspect, and more about the sentimentality about who it was gifted to?

The fact that it meant so much to him, and that I could do something in such a pivotal and upsetting, just a crazy time in his life, the fact that I could offer anything that would somehow make him feel… I don’t want to say better, because I don’t want to imbue myself with that power, but to help him along, that was really meaningful to me.

That brings me to ask about your barter system… can you expand upon that and why that’s the model that works for you?

It’s kind of evolved through the years, but it has always been the same kind of sentiment. It was awfully hard for me to just design things, and sell them, it’s never been my rai·son d’ê·tre, I didn’t start cross stitching with great aspirations or to make money, I literally just fell backward into having this skill, and I was crazy good at it.

I was inspired by the artists around me, it’s hard to be like “Hey you inspired this, it took me 60 hours, and now I need you to give me a couple of thousand dollars for it,” at the beginning of a career, that’s almost impossible. So I would just trade people for stuff.

To me it was like, you Dane, can give me $20, the same $20 that Chance the Rapper gives me, and it’ll be the same $20, it’ll go as far. But if I’m trying to do a hip-hop project, 20 minutes from you is going to be a lot different than 20 minutes from Chance the Rapper. There is so much worth that we forget about people because we’re looking at the bottom line of things.

Inviting money into a conversation about art inherently changes all of it, and I’m not interested in that at all. We spend our whole lives running around trying to make a paycheck, trying to pay our bills, trying to get richer, bringing that into art is tricky business and I didn’t want to have to deal with that.

And it’s paid off in spades!

People think I’m crazy for doing it, but honestly, all the opportunities and the things that I’ve traded for have been so much more meaningful and worthwhile than money. That money would’ve been spent, and I couldn’t even tell you on what. The experiences from the bartering has just been so much more exciting to me.

It also means I don’t have to weigh myself and put a value onto myself. Forcing yourself to find value in your work and basing it on something is just inherently evil and corrupt, it doesn’t appeal to me. I make some money off the cross stitch stuff, but it’s with brands, I don’t barter with brands. Brands are not people, I allow brands to pay me and that funds the rest of the stuff.

How much input, if any, do the artists contribute to the design, and who has been your favorite to work with?

It really depends on the artist. I think that there has only been once or twice where an artist has been like “hey can I have this specific thing?” And I’ve said “Yes.” I don’t do that very often, I don’t find much joy in that, that’s just labor. In true collaboration, I’d say the input and design process is more nebulous. When I can, I like to talk to artists about themselves and the things that they love, and the things that are meaningful to them. Through that, I’ll often figure out the visual thing.

I don’t ask like, “What’s your favorite color?”

I had an outfit that I made last summer, and in our consultation talk we talked a lot about balance and equity, and that informed the entire design of the piece. You may not know that by looking at it, and there are no visual references, but when they saw it they were like “Oh, yeah of course, that’s exactly it!”

The input is like a conversation.

I loved doing stuff with SZA, she was really fucking wonderful and very giving of herself and generous with who she is. She was very lovely! She might be one of my favorites.

When you’re making a design in memoriam, what is something that you try to keep in mind? I notice those pieces have a way different vibe than your other pieces.

I want them to be peaceful and protective. The end goal with all the in memoriam pieces is to have them with the people they’re supposed to be with. Eventually, in the next couple of years, I’ll do a show, and I’ll show them off and send them back to their respective people. I did a Fredo Santana one, so when his son turns 16, he’s like three right now, I’m going to give him the jacket.

Mac MIller’s mom has already seen the jacket, and I have my route of getting it to her, so after my show, I’ll give Mac Miller’s jacket to his mom. I don’t explicitly put the ask out there to connect me, but the people always find me, it’s very strange. The Nipsey Hussle one is going to go to his sister, they’re all made with that in mind, this is a piece that is going to be with this person’s loved ones — I want it to feel peaceful and protective.

Right now, it seems like things like embroidery, cross-stitching, other hand made touches seem to be enjoying a new level of appreciation in streetwear, why do you think that is?

We’ve reached the end of Western Civilization, everything is a remix! Streetwear is such an interesting place, a lot of what we call “streetwear” is basic tops and bottoms, rewriting the rules on those, and even the classical silhouettes, is very difficult. It’s really hard to come up with something new and interesting, so when you have a handmade process that thing is inherently different and unique and one of a kind. I think what we’re trying to do when we’re living out loud with our fashion is, we’re trying to differentiate ourselves. We’re communicating, who we are through what we have on us. Having something that is handmade or that has had a lot of work put into it, you can feel that in the garment. It’s heavier, most substantial, it feels richer and nicer.

Are there any labels or brands out there that you really like what they’re doing?

Pyer Moss, I love Pyer Moss so much. Some of my favorites in Chicago — Sheila Rashid, she does the best denim. Alex Carter, she was just on Project Runway last season I believe. Kristopher Kites, he does… it’s going to sound so bad if I just say plastic necklaces, but he does a lot of really great jewelry and shirts.

And of course, streetwear god of Chicago, Joe Freshgoods.

Do you have any plans to make embroidered face masks? We’re always looking for cooler face masks

I actually just did one! It’ll probably be out once this article goes live. The problem with embroidered face masks is they have a lot of holes, obviously, so you have to be careful with how you construct them.

Because of the pandemic, we’ve reached a point where a lot of industries are being forced to hit reset — hopefully for the better. What do you hope to see in the fashion industry moving forward?

It’s the same thing I’d like to see across all industries — honesty and truth. I think we have a big problem with mass production in fashion, it’s really bad for the planet, we don’t talk about it, it’s not really studied and no one regulates it. It’s a big big big big problem.

It would be great to address that, fashion has so many wonderful and amazing things about it, but it also has a lot of deep dark holes. Traditionally it’s been a very exclusionary industry, racist, misogynistic, all those things. What’s interesting about this time period, with the pandemic and what is essentially the second civil rights movement, is that all the wiring is getting exposed. I have full faith that the bad wiring in fashion will be exposed sooner or later anyway. Bad practices under pressure don’t net very good results. It remains to be seen what will actually happen, but I would love if we can address environmental impact, and sexism and racism in fashion, that would be tight.

I would love to see more woman streetwear designers. More Melody Ehsanis. It would be really cool to see women take a much more prevalent role in streetwear, we’re doing it, it’s the best it’s been but there is so much more to do!