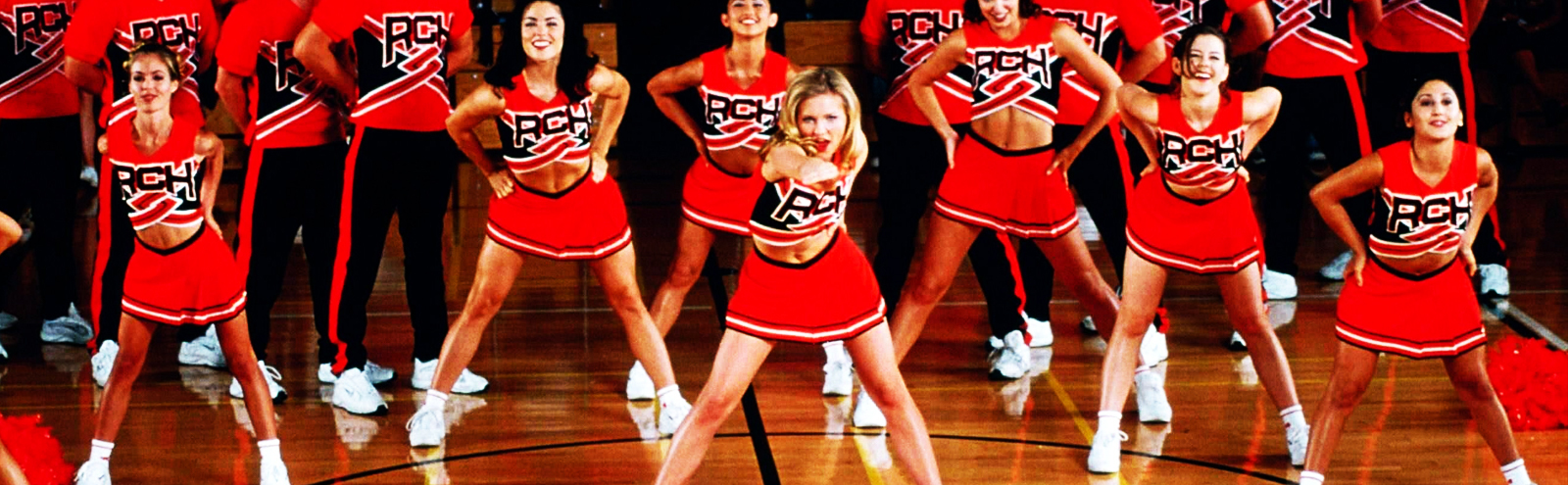

When Bring It On landed in theaters 20 years ago, it ushered in a different kind of teen comedy. Gone were the John Hughes days of pining after men in red sports cars and forging fragile friendships from days in detention. Instead, high school had become a satirical battlefield where some of the most unfair, outdated social customs were thrown in the trenches, stuffed with grenades, and blown up for the world to view their uglier entrails. Clueless pioneered the art form, and Bring It On perfected it, upending tropes and making cheerleaders (leaders of the social caste at that age) the underdogs. These were people that you rooted for, laughed at, and wanted to be like — not because they were pretty and popular, but because they were strong, driven, and could stick a front handspring step-out round-off back handspring step-out round-off back handspring round-off full twisting layout.

Ranking the cheers of Bring It On is pointless — they’re all flawless — but for the film’s anniversary, we decided to dive into the movie’s opening dream sequence. It’s a routine that sets the film’s very high bar. A masterclass in storytelling. A risk-taking introduction to a film no one believed we’d be talking about decades later. A GIF-able empowerment anthem?

Here’s how Bring It On’s cheeky opening number got made.

The Pitch

For writer Jessica Bendinger, who’d spent time covering the late ’80s hip-hop scene in New York for Spin Magazine, the genesis of Bring It On was a childhood spent watching ESPN cheerleading competitions on her aunt’s couch and an abiding love for Public Enemy’s Yo! Bum Rush the Show. But getting a studio to sign onto a teenage satire centered on cheerleaders took some convincing. Like, years of convincing. The project languished at Universal for years before getting a pick-up thanks to the interest of names like Tom Hanks and Silence of the Lambs director Jonathan Demme. But that didn’t mean that anyone had high hopes for how the movie would turn out.

Jessica Bendinger (writer): We were in pre-production before we had a director. That’s how little confidence and attention was being paid to the movie.

Peyton Reed (director): Yeah. I got sent the script by my agent. It was called Cheer Fever at the time. I had been looking for a script to do my first feature, and I really loved the idea of doing a high-school movie. I really didn’t know that much about competitive cheerleading, and Jessica had written this thing that just painted such a vivid portrait of that world and that subculture. It was funny, and it was extremely visual, and it was something that I’d never seen in a movie before, and those things all appealed to me.

Bendinger: Thank goodness.

Reed: That whole first three pages, that was the opening cheer, which I think remained almost verbatim within that first draft. I don’t think we changed it much at all. It just grabbed you from the beginning, and it confronted your preconceived notions about cheerleaders, and it introduced all these characters, and it was just funny, and I was like, “Wow. This is different. I haven’t seen this in a movie, and as a movie-goer, this is something I want to see.” I felt like you could really surprise people.

It was only after I read the script and eventually signed on to do the movie that I found out that Jessica had been trying to get this made for a long time. You sent it out to a ton of people, right?

Bendinger: I had 28 pitch meetings and 27 “No”s. Late summer of 1996, in an old Saab with no air conditioning. I drove around studio to studio trying to get somebody to buy it, and I’d pretty much given up by the time I finally ended up at Beacon [the company that would eventually produce the film].

Reed: I think it’s one of those things [where] studios always say they’re looking for something new and different, but the thing that scares them the most is something new and different. Really, Jessica’s perseverance got the thing made.

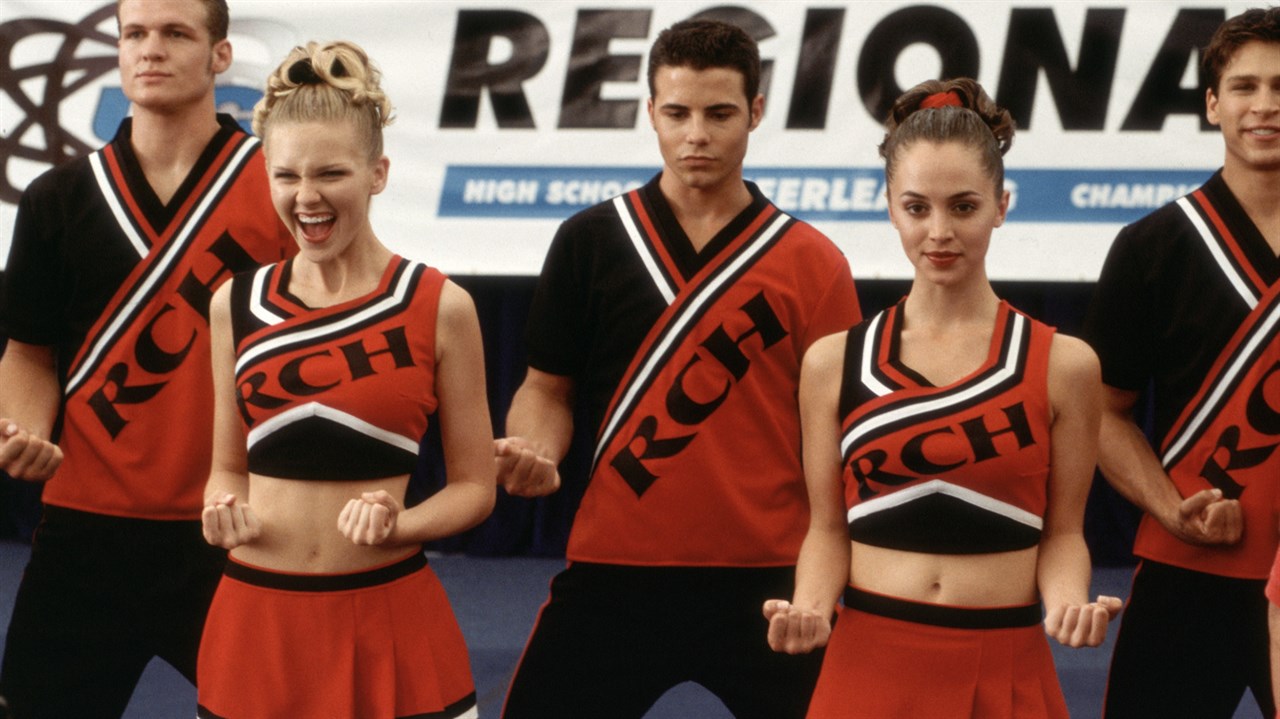

Welcome To Cheer Camp

The cast of Bring It On was comprised of a group of largely unknown actors. Kirsten Dunst was brought on as the lead with Gabrielle Union playing her rival and Eliza Dushku as the lovable outsider who introduces audiences to this world of camp and chaos. But the rest of the lineup was untested and unprepared for the physicality of pulling off competition-level routines, so the producers sent them to cheer camp.

Lindsay Sloane (Big Red): When this was being cast, there was another cheerleading movie called Sugar and Spice that was being cast at the same time. It was weird because it was like rival cheerleading films, but being a girl in that age group in L.A. trying to get a job, it just felt like a madhouse, people rushing to try to get into one of these movies.

Nicole Bilderback (Whitney): Oh, that’s right. I believe I [auditioned for] that.

Sloane: When I got cast as Big Red, I remember reading the script and being like, “Oh my God, I’m horrible.” But it’s also why I loved playing this part because I got to be unapologetically who I was and unabashedly sexy and confident. The irony is I literally thought I was getting fired every day from this movie. The fact that I was playing someone that was so badass was such a contradiction to what was happening in my inner soul because I showed up, and there was actual cheer camp to learn these cheers. I showed up a week into all of the girls already being at cheer camp. I just assumed we were all actors that just lied and said we knew how to dance and cheer to get a job.

Bilderback: I was actually a cheerleader when I was younger. I remember I went in and I read for the casting director and for Peyton. We had our slides and we basically just had to perform our scenes. The call back of course was in front of literally all the studio executives and the producers and it’s a huge intimidating deal. We had to not only do the scenes with our lines but then we had to choreograph a two-minute cheer. If I remember correctly, it was pretty badass. I choreographed a cheer dance to “Micky,” which is at the end of the movie. That was not planned.

Sloane: I think in the audition maybe I did a split and maybe I did a cartwheel, but they didn’t really do a thorough investigation of who has the ability and who doesn’t. So I walked into this cheer camp and they had mixed our actors with professional cheerleaders and they had already learned one major cheer by the time I got there, and I walked into the gym and saw the cheer and was like, “Oh shit, I’m toast. They are going to so quickly see that I do not know what I’m doing.” So the entire shoot up until the very last day, as a running joke, I was like, “So do I still have a job?”

Anne Fletcher (Choreographer): She’s so wrong. She was so perfect. I don’t even know what she’s talking about.

Sloane: I showed up, I was like, “Oh, this is real. There are people throwing actors up in the air.” I mean, I wasn’t in any of the stunts, so I got saved that way. There was one girl, I don’t know if anyone has talked about it. I don’t remember her name, but I also wouldn’t say it if I remembered it, but someone did get fired after the first week of dance practice.

Fletcher: I was an assistant choreographer and dancer for years with Adam Shankman. So it was actually my first movie on my own. It just was completely out of my wheelhouse. We were in San Diego when we shot this. We had a handful of younger kids who were the base of both teams — this is what they do is competition cheerleading, and then I would plug in our actors. The cheerleaders themselves, they’re accustomed to that every day. But for the actors, they don’t know anything about this. So it was a lot of fun being with them and watching them fall and figure it.

Bilderback: It was Monday through Friday, every day. We’d wake up early, we’d get picked up, and then we would head to a gym that is specifically for cheerleaders. We started with learning all the dance routines, and then of course we had to train and learn specific stunts before actually putting all the routines together. While we’re doing it mind you, we’re having to learn the lines for the film. It was just full-on. Of course, we’re also all hanging out afterward and drinking, because we’re young and it was like a college experience. So when you’re young and you’re drinking, no matter how late we’re all up the night before, we were still able to get up early in the morning and still function and learn everything. It was a ton of hard work.

Sloane: We thought, “It’s going straight to video so let’s have the time of our lives.”

(Almost) Getting Cut

The film’s opening cheer sequence plays on the “just a dream trope” but its tongue-in-cheek tone sets up the film in a very singular way. Bendinger and Reed both believed that was the perfect way to kick off the movie, but they faced pushback from studio execs.

Bendinger: Jon Shestack, God bless him, did ask about cutting it. And I said, “Are you fucking kidding me?” First of all, people either love or hate cheerleaders. There’s no middle ground. You have to let them know we’re in on the joke. You’ve gotta talk about performative femininity and internalized misogyny. Obviously, I couldn’t say that back then, but you’re addressing all this stuff that we can now speak about. There were some notes about the lingo from the not-so-cool kids who didn’t get it.

Reed: For me, that opening does three things right off the bat. It’s some of the most efficient screenwriting I’ve read because you are introducing a handful of characters right off the bat, and then secondly, it confronts the audience’s preconceived notions about cheerleaders in a really funny way, and three, it just sort of announces the energy of the movie. It comes at you from the very beginning. It has the energy of a cheerleader. It’s like the movie itself is a cheerleader. That’s what grabbed me from the beginning.

Fletcher: It sets up the camp.

Sloane: Most teen movies were set up the exact same way. I felt like this instantly went into that dynamic. I also think that everyone’s little shout out was a nice little moment, like a glimpse at who they’re going to be in the film. Then you do go into a trope high school movie moment where she’s having the dream that she’s naked, but it just felt representative of much larger stakes. This is not just about a girl who wants to be liked and wants to be popular. This is a girl who wants to be very good at the thing she’s committed a huge chunk of her life to, and she’s strong, and she’s fit, and she wants to succeed. I loved the messaging of it.

Bendinger: I fought for that. The producer of a giant flop, I will not shame him and name the movie, but I will say this. He said to me, “Girls don’t go to movies.”

Reed: That’s one of the most wrong-headed comments I’ve ever heard about the movie business. It’s just wrong.

Bendinger: Thankfully, I didn’t listen to him.

Finding A Comedic Rhythm

Shooting the opening scene took the cast a full day filled with multiple takes in a crammed auditorium with 100 extras looking on. In the script, Bendinger described the vibe as Clueless meets Strictly Ballroom, but it was up to Fletcher and Reed to interpret the dance, and the foundational tone for the film, in a two-minute frenzy of short skirts, sexual innuendos, and hilariously literal dance moves.

Fletcher: The way Jessica wrote the words and the way the song was orchestrated, it just spoke to me that it had to be literal choreography. There’s obviously cheerleading-esque choreography in the opening number, but If you watch it, it’s literal. The girls are doing the movements of the words, because I’m like, “That’s the only way I can see this being hilarious. It’s so stupid.”

Sloane: I remember all of us, we made up those [quick character intros] on the day. It was like, “What do you want your little move to be?” and us trying to think of a move that represented who we were.

Fletcher: We worked together. Actors will know their characters way more than any even more than the director because that’s their only job. So I always go to them and ask “Do you have an idea? Do you want to try something? Let’s talk about that.”

Bilderback: I remember thinking, “It’d be kind of funny to slap my ass.” I was kidding. I was joking, but then [Anne] was like, “Actually, okay, so show me what you were thinking.” Then Anne came up with the part that I do at the very end with my hands — my fingers sliding across each other.

Reed: I think the opening cheer might have been the first routine that we shot. I’m sure we had like a day. It was very fast.

Fletcher: Trust me. I’ve had directors ask me how I should shoot something as a choreographer, and there’s no shame about that. To shoot dance, it’s a different thing. Peyton never asked me. Peyton is so rock solid. I tried to design it in a way that they could shoot it and have fun shooting it, like the crazy lines, the separations, the overhead shots, the peeling apart of the line. Certain things, I just wanted to make sure that Peyton had fun.

Bendinger: I talked about Esther Williams, which Esther Williams implies overheads because it was all water shots and synchronized swimming. Busby-Berkeley-esque. All that stuff introducing the Toros, the single shots of introducing all the different cheerleaders. That was all in the script. You could feel the energy of it from the page, but he totally met the opportunity and rose to the challenge.

Reed: And that energy was fun. I really did genuinely feel like a camp counselor on that movie, because everybody got along great, but they’re kids. They were teenagers.

Sloane: I remember being in the school gym all day long for that one and having really long breaks, and then you have to reboot and do it all over again.

Bilderback: It’s actually really hard because you’re having to do it over and over again. It is a lot of technicalities that I don’t think people think about.

Sloane: I think we maybe did it for 100 people at one point. We didn’t get the energy of really doing it for a full gymnasium or people. You’re wanting the 100 people to really fill the space and make it still feel like it’s so many but it’s just like, you get one slow clap at the end of it. But we were so enthusiastic that we clapped for each other.

The Legacy

The film’s sharp takedown of everything from sexism and high-school social hierarchies to cultural appropriation is finally starting to be appreciated, 20 years later. The cast and crew knew they’d made something special once filming was done, but the reaction to the film, and its lasting power was something that no one expected.

Reed: We did do some screenings early on for cheerleaders. I remember it because a couple of our actors put on disguises and snuck into that test screening so they could see the movie before everybody else.

Sloane: I snuck into a test screening because it was in Chatsworth, which is where I grew up and I was just like, “It’s a sign. I have to be there.” So I put on a wig and a baseball hat because I knew that if Peyton saw me, he’d be like, “Sloane, get out of here.” I remember sitting in the front row because it was the only seat that was left, and then all of a sudden this movie starts and it is larger than life and it blew my mind. Everything worked. It was so funny. It was so inspiring.

Reed: I remember going around opening night and driving around the various theaters in Los Angeles all over town and just being thrilled that anybody had shown up.

Bilderback: [At first] we were like, “Okay, we’re doing a cheerleading movie.” But we didn’t care because we knew it was a big studio, we knew that the producers involved were huge. Of course, we’ll do it because we’re getting paid, and we’re actors, and this is what we do. But we had no idea that it was going to be as successful as it was. And then when it was, all of a sudden, we’re like, “Hell yeah, we did a cheerleading movie!”

Sloane: I don’t think that I had the wherewithal in my youth to realize that we were a part of a feminist film and that the message was so inspiring. I love this message of this movie. I was just listening to the words in the opening song and how empowering those words are, “Hate us because we’re beautiful, well we don’t like you either.” We’re not sorry. We’re hot, and we’re good. It’s become like an anthem that people play to lift them up and give them the confidence that they need in life.

Bendinger: I think we were talking about [a lot of] things — whether it’s cultural appropriation or socioeconomic inequality or becoming a better person, going on the journey of being from being shamed and humbled to trying to make something right and still making more mistakes. Growth is not perfect. We learn our moral compass through sometimes being a few degrees off, and to me, I’m very proud that that is there. I hope it’s a powerful proxy for people. It’s not about being perfect, but it’s about engaging in the journey in a meaningful way and being willing to make those mistakes. That’s the heart of the movie that touches me that I’m glad that’s so intact.

‘Bring It On’ celebrates its 20th anniversary on August 22, 2020.