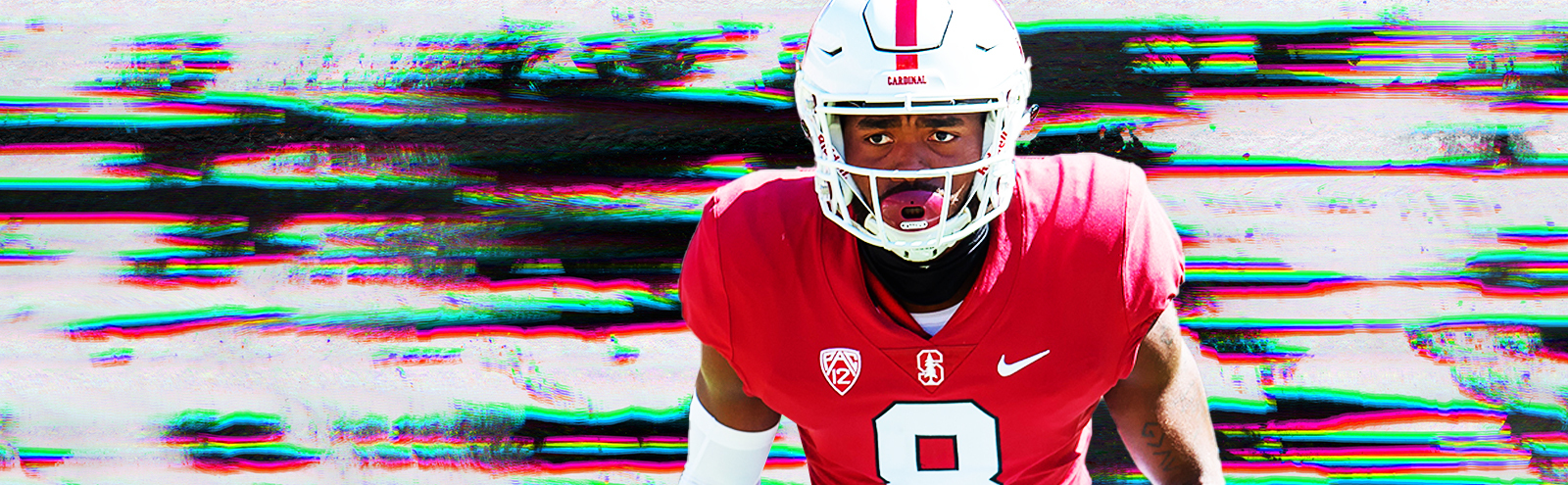

Stanford fifth-year senior defensive back Treyjohn Butler, like every athlete in the Pac-12, isn’t playing football right now. Still, he still found himself earning quite the honor when he was named to the Allstate AFCA Good Works Team, along with the likes of Trevor Lawrence, Chuba Hubbard, and Sam Ehlinger.

Butler is active in the community, working with kids through various organizations. This year, has partnered with his church to help provide food for low-income households, as well as pushing his church to allow local kids to use the wifi for remote learning. He’s also been among the leading voices in the Pac-12’s We Are United players coalition, which has brought athletes from all sports together in the conference to call for better health measures amid the pandemic, a seat at the table to negotiate for a revenue split, and much more.

On Wednesday, Butler spoke with Uproxx Sports over the phone about that work he does off the field, why he feels so strongly about working with kids and giving back to his community, the continued efforts of the We Are United coalition, and how conversations have changed within the Stanford locker room about real-world issues as players become more educated on problems facing the Black community.

First, how are you doing right now?

I’m doing good. Blessed, humbled by the opportunity. Like, a little bit frustrated by the recent announcement of the indictments in the [Breonna] Taylor case, but still grateful for everything going on.

What does it mean for you to be named to the Allstate AFCA Good Works Team?

To me personally, it’s truly humbling because a lot of work has been put in behind the scenes. A lot of my peers can attest to the fact that, I personally am not for show, I’m all about the greater good and impacting lives as much as we can. I never put myself first and that’s something I keep trying to embody each and every day, using the virtues that my mom instilled in me as well as my grandma. Trying my best to resemble my mom each day and try to be there for everybody. And to be a part of this prestigious group, it takes the words out of my mouth.

At times I’m still trying to process this because not a lot of people have been part of this group, and it represents so much more than the work we’re doing and shows how much more work we need to do together. I think it’s also beautiful because other people select the people that make it, and it’s again a humbling process to be a part of.

You do a lot of work with kids, whether through San Bernadino County children’s services, Read Across America, your church, or Stanford’s work with kids with chronic illnesses. What made you want to give back in those ways to kids in your area and use the platform of being a player at Stanford to do that?

The biggest influence for myself – Pasadena, California we were blessed with the belated, one of our coaches, Coach Victor, an LAPD officer, had an organization in Pasadena called Brotherly Crusades. That organization was year-round. It had every sport. It kept every kid on the field and on the court, the same faces. We ran track together, played football together, basketball, everything together. And the impact he had on the community was so great, because a lot of kids could’ve went the other way, dealing with drugs or gang violence, but he kept so many kids safe. And recognizing how much impact he had on my life and the lives of other guys that were in that same group, cause when I was in high school, I got to witness the fact that a lot of the guys and girls that he coached became D-1 athletes, and that’s how much of a great impact he had and at that moment I knew I needed to give back. As well as the amount of mentors I’ve had in my life, growing up in the household I did, having a single mom, you appreciate the people who take the time out to invest in you. That’s something I knew I had to pay forward, whether that’s helping low-income households with food discrepancies or allowing their kids to have access to training, or anything.

You know, helping with school cause sometimes that’s a hard area for kids to deal with, and personally I knew I had to take a passion for. Because if you can reach one, at the end of the day, it’s going to have a greater impact than not doing anything, and that’s a motto of life I’ve been trying to live by. Along the way, meeting other people who have been pushing me to keep doing more work.

We’re in this moment where we’re in this fight for systemic change and recognizing how much the system is against so many people and I think it amplifies the importance of coming together as a community and working together as a community to help each other while fighting for something much broader. Is that something you’ve really felt in recent years, especially this year with everything going on?

Definitely, COVID alone showed me how different household situations are. I had a chance to talk with Stanford alumni Chris Draft and I asked him, “What more can we do? Because I feel like we’re not doing enough.” And he wasn’t sure where I was coming from, but I told him I felt off about just providing meals like that wasn’t enough. And he highlighted to me how important the meals that we were doing and we can get more food from the church to provide to the low income communities because how much of the low income areas are food deserts, aren’t able to get fresh produce, and everyone’s dealing with possible unemployment due to the pandemic and not being able to afford getting the proper stuff for their household. That having an effect on kids, not being fully nourished and not being focused in school.

That stuff became more evident, along with challenging our church to have wifi for kids to come, whether they’re just outside at the tables to be engaged with school is a big thing that was evident here in California alone during this pandemic for kids who weren’t able to stay focused in school.

Yeah, and I know on your profile you also work with the Ujamaa House at Stanford. How did you get involved with that and what has it been like being a part of working with other students to really explore Black history and culture, particularly given this moment in America?

The beginning part of that was a blessing, because a lot of times for student athletes you don’t get to stay fully engaged with your campus and school like other students. As a freshman student, I was blessed with the opportunity to reside there and I forced myself to stay engaged with my community at my school by attending programs. You know, OBMI, you got a chance to recognize it’s a lot greater than being “of color,” you know? There’s Black women, being in the Black LGBTQ community, there’s all these different spectrums of stuff you need to recognize and intersectionalities that all intertwine. And in my junior year I had the opportunity to come on staff and truly challenge those who were willing to stand up and present these different cases, and it’s beautiful.

You learn something new every day. You’ll be lying to yourself in thinking you know it all. But to be able to foster community where everybody’s welcome – there’s no one person allowed – to be able to come in that room to learn, to discuss, to share, and to grow. And that’s the biggest thing that I take from that is each and every time we stepped in that room, there was a growth among almost each and every member in there.

You mention fostering a community and I think it’s something we saw this summer in the college athletics community, with the Pac-12 United and then the We Want To Play coalition, calling for major changes in the collegiate athletics system. I know you’ve said that the work has to continue, even as the Pac-12’s not playing football now but there’s some discussion, like the Big Ten about possibly reinstating the season. What have the continued conversations been like among the players at Stanford and across the Pac-12 and across the country?

The conversations have ultimately still been pushing forward about social justice and racial issues. The big push for speaking up for Black women and the stuff that they deal with. Allowing them to have the space to speak up, we’ve been trying to have Zoom calls where they can share with us things we don’t see as men, as other athletes, so they can have a great platform.

In addition to that, the foundation is having a players’ coalition. Continue having that current connect to our athletics department at our schools and also in the Pac-12 office. Keep talking about stuff, because there’s no reason we can’t still communicate. Personally at Stanford, each athletics department here has made sure everyone is registered to vote. Speaking up and fostering the community to have conversations with the police department about different things. As well as, I have the opportunity to be part of this smaller group where we work with the Stanford athletics staff and how they can become better when dealing with social issues and different things that are going on in our country.

Getting back to the We Are United, it’s staying focused, not wavering, and keeping the stuff at hand. We will acknowledge the fact that a lot of things have happened, from guaranteeing eligibility to ensuring better health measures, a lot of stuff we’re really proud of happening, but stuff continues to happen that we’re still upset about. The fact that today is going to be a tough day for a lot of people because of what happened in Breonna Taylor’s case. Acknowledging what happened, only charging one officer with a charge that’s not even about the murder. So, stuff like that is still evident and more of a priority for us and where our hearts and minds are at.

Absolutely, it has been another example of this system working in a way that doesn’t work for the people as a whole. How have you seen in your time at Stanford conversations among players change about what’s going on in the country, and do you feel like there’s more conversation in the locker room about things that are going on that effect you guys as men and not just as athletes?

The conversation has definitely changed over the last four, five years. Like, I was on this campus when the two incidents happened in the summer of 2016 in Ohio and down in Louisiana, and it was weird because there was so much anger. There was no education on the matter. There was no proper knowledge on how to speak on things. I can admit when speeches were made it was made out of ignorance, not a lot of facts to follow it up. But over the course of these four years, the amount of education, the amount of time invested individually and collectively for the things that happened this year in 2020, the power in the voices was so much greater because there was knowledge behind what was being said. There was no room for someone to be upset with ignorance because there was none. There was passion and power in the words stated, and collectively as a group people can agree and challenge themselves to read more and learn more. And that’s what’s been the biggest difference over the past few years is watching how much power has been able to grow behind the words that have been stated from each individual player. Recognizing the power they have as a student athlete and they’re not just somebody that provides people with entertainment.