With Ron Howard’s high-profile awards movie, Hillbilly Elegy hitting Netflix this past week, just a few months after the lower-profile release of the much better The Devil All The Time, hillbilly movies are suddenly all the rage. For my money, the best hillbilly movie is Winter’s Bone. But long before that we had Deliverance, if not the “original” hillbilly movie, arguably the original prestige awards-bait movie about hillbillies.

The 1972 best picture nominee embedded the phrases “squeal like a pig, boy” and “you got a purdy mouth” so deeply into the fabric of pop culture that I knew them long before I ever saw the movie. Those lines, along with “Dueling Banjos” and the “inbred” banjo boy, have been homaged and parodied so many times that Deliverance‘s status as “the squeal like a pig movie” has long since eclipsed anything else about it. But is that all there is? How has the legacy of Deliverance affected the cinematic portrayals of hillbillies we get today?

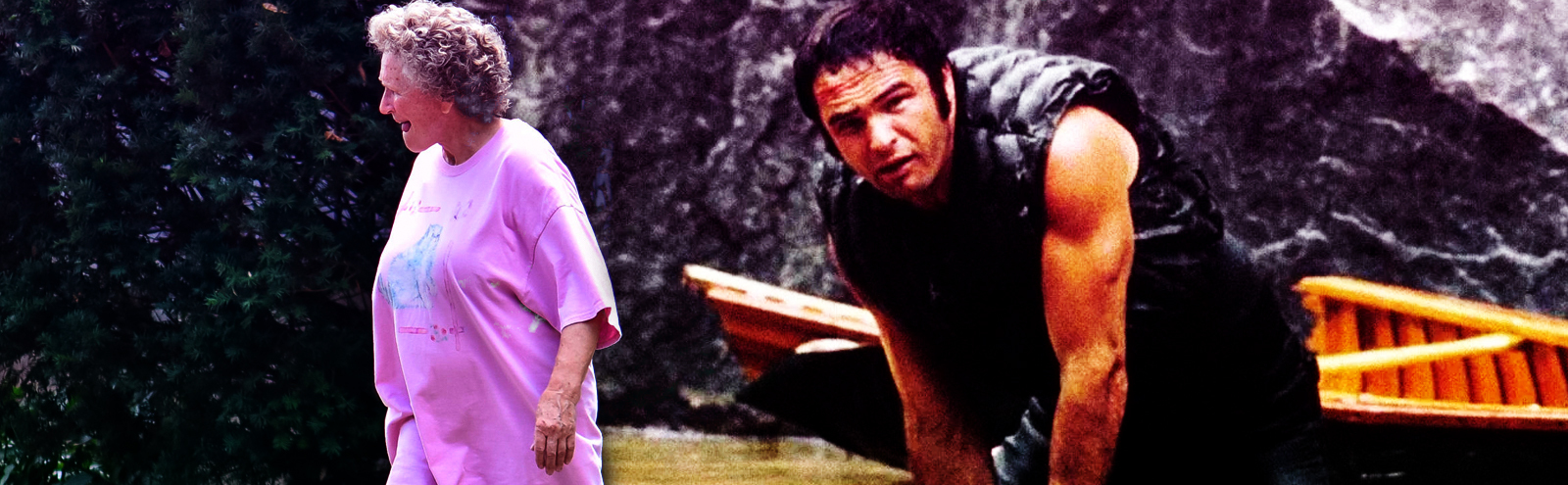

The film follows four friends from suburban Atlanta — Lewis, Ed, Bobby, and Drew (played by Burt Reynolds, Jon Voight, Ned Beatty, and Ronny Cox) — on their trip to canoe down the Cahulawassee River in north Georgia. It’ll be their last chance to see it before a new dam turns the whole area into a lake. The film was an adaptation of a John Dickey novel, and Dickey’s Cahulawassee was supposedly inspired by the Coosawattee, in the Blue Ridge mountains, which was dammed in 1974. Thus the four are the proverbial city boys traveling into America’s heart of darkness searching for Eden, only to find an indifferent mother nature and primordial evil, in the form of inbred hillbilly rapists.

Within that structure, Lewis (Burt Reynolds) and Drew (Ronny Cox) are a sort of middle-aged Jack and Ralph from Lord Of The Flies; Lewis as the dog-eat-dog hunter survivalist Jack, and Drew as the literal guitar-carrying Ralph, who just wants to play his music in the sun. Beatty’s Bobby, meanwhile, plays the Piggy, an insurance salesman who Lewis instantly nicknames “Chubby,” even though, by 2020 standards, Beatty is barely overweight. They stop at a gas station along the way, where they spot a handful of flea-bitten locals (“talk about genetic deficiencies, isn’t that pitiful?” says Bobby) who are at least smart enough to recognize the condescension radiating from their city betters. Drew starts a jam session with the inbred-looking “Banjo Boy” in the famous “Dueling Banjos” scene (the song won a Grammy in 1974), leading us to believe that maybe this whole getting back to nature thing is going to work out just fine.

It was obvious even then that with these obvious parallels to Heart of Darkness and Lord of the Flies, Deliverance was trying extra hard to do a symbolism. In his original two-and-a-half-star review in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert wrote, “Dickey, who wrote the original novel and the screenplay, lards this plot with a lot of significance — universal, local, whatever happens to be on the market. He is clearly under the impression that he is telling us something about the nature of man, and particularly civilized man’s ability to survive primitive challenges.”

Storytellers tend to fall back on symbolism when their story feels like it’s missing something in terms of either import or believability, and Deliverance feels that way. After cocky macho guy Burt Reynolds — who appears to be wearing some kind of wetsuit vest, which seems like a self-defeating choice of clothing on few different levels — pays filthy yokels the Griner Brothers to drive their cars downstream, the group sets off down the river. Everything is going just fine until a different set of filthy, toothless hillbillies holds Ned Beatty and Jon Voight hostage in the woods with a shotgun, raping Beatty and about to force Jon Voight to perform oral sex just as Burt Reynolds finds them and shoots one hillbilly dead with a bow and arrow.

With the benefit of hindsight, there seems to be more going on than just the overt modern vs. primitive conflict that audiences would’ve noted at the time. Arguably even more obvious in 2020 is how much Deliverance feels like “Easy Rider on the water,” to use a Hollywood shorthand.

In his recent book, The People, NO: A Brief History Of Anti-Populism, historian Thomas Frank positions Easy Rider as the defining film of “The New Left,” a movie about free-loving, dope-smoking drug runners getting murdered by bigoted rednecks. It was released in 1969, at a time when the counter-culture was consciously beginning to distance itself from the rural and working class, who had traditionally been part of the Democratic coalition but who the counter-culture had come to blame for the Vietnam War. It’s a fairly uncontroversial point to make about Easy Rider, considering its screenwriter, Terry Southern, said as much himself. As Southern described the ending, he intended it as “an indictment of blue-collar America, the people I thought were responsible for the Vietnam War.”

It’s hard not to see Deliverance, released three years later, as reactionary in many of the same ways. It portrays human hillbillies as inextricable from mother nature, basically part of the landscape, and representatives of the primitive. “Za ovahwhelmink eendeefference of nature,” as Werner Herzog describes the bears in Grizzly Man.

Toothless, inbred, and perverse, the yokels are sort of mindlessly predatory. Whether out of envy or genetic predisposition, it feels a bit like the sixties hippie equivalent of “they hate us for our freedom.” And why not, it’s easier on the ego to assume that everyone who doesn’t like you is an unchangeable state of nature rather than a human being with free will who has made a rational decision that you suck.

Of course, Deliverance‘s anti-working class theme isn’t the only thing going on in it, and in some ways it’s softer than Easy Rider‘s. Thomas Frank notes that Easy Rider, starring Peter Fonda, whose father was in Grapes of Wrath, was an explicit rejection of the previous generation’s politics. Yet it’s notable in Deliverance, that, after being raped and savaged by dangerous yokels, the surviving group does arrive in town to find that the Griner Brothers have indeed parked their cars for them right where they promised. There’s even a group of “nice hillbillies” nearby, with the family belongings stacked atop a pick-up bed and a kid sitting on top in a chair, a clear echo of Grapes Of Wrath.

Still, when a local notes that everything in the town is about to be drowned underneath a lake, he says “that’ll be about the best thing that ever happened in this town.” The Sheriff gets more or less the final thought, saying “I’d kinda like to see this town die peaceful.”

In that way, Deliverance is an actual elegy to a hillbilly lifestyle that Hillbilly Elegy is not. It’s hard not to be taken by the romanticism of it. The church cemetery featured in the film actually is now hundreds of feet underwater, just like the movie said it would be. It actually is the literal glimpse at a lost landscape it says it is.

It’s hard to believe Hillybilly Elegy would exist if Deliverance hadn’t, that JD Vance would’ve felt compelled to write his memoir if he didn’t feel the sting of city slickers thinking his home people were all toothless raping hillbillies. Hillbilly Elegy feels to some extent like it grew out of a perceived slight, responding reflexively and defensively and using the same language of movie tropes. Thus it feels trapped in the same cycle of reheated culture war recriminations, which is maybe part of why it’s been so poorly received.

Yet you don’t get much sense that Vance has lost anything once he goes to Yale in Ron Howard’s movie. He’s simply outgrown the other hillbillies. He’s pulled himself up by the bootstraps and now he’s gone. It’s a statement of identity more than anything else. Deliverance is at least romantic about the landscape, even if it couldn’t quite see the people in it. When Ned Beatty’s character says that there’s something about the woods that we’ve lost in the cities, Burt Reynolds’ answers, “We didn’t lose it. We sold it.”

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.