History books are filled with photos of people we know primarily from their life stories or own writings. To picture them in real life, we must rely on sparse or grainy black-and-white photos and our own imaginations.

Now, thanks to some tech geeks with a dream, we can get a bit closer to seeing what iconic historical figures looked like in real life.

Most of us know Frederick Douglass as the famous abolitionist—a formerly enslaved Black American who wrote extensively about his experiences—but we may not know that he was also the most photographed American in the 19th century. In fact, we have more portraits of Frederick Douglass than we do of Abraham Lincoln.

This plethora of photos was on purpose. Douglass felt that photographs—as opposed to caricatures that were so often drawn of Black people—captured “the essential humanity of its subjects” and might help change how white people saw Black people.

In other words, he used photos to humanize himself and other Black people in white people’s eyes.

Imagine what he’d think of the animating technology utilized on myheritage.com that allows us to see what he might have looked like in motion. La Marr Jurelle Bruce, a Black Studies professor at the University of Maryland, shared videos he created using photos of Douglass and the My Heritage Deep Nostalgia technology on Twitter.

The effect is simply stunning.

Here’s another animation of Frederick Douglass that @jcdmce generated earlier today (which got me hooked on these a… https://t.co/YlJ2yJoAj1— La Marr Jurelle Bruce (@La Marr Jurelle Bruce)1614500560.0

(It may be worth noting here that Douglass deliberately never smiled in photos, as he wanted to counter the common narrative and caricature of the “happy slave.”)

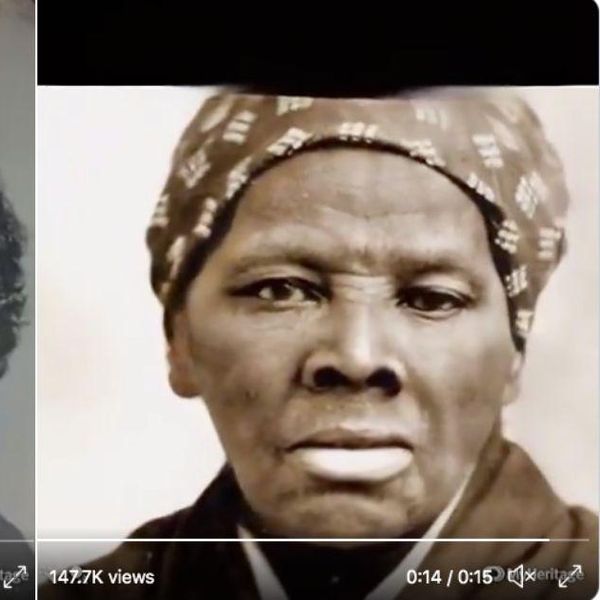

Another Twitter user created a colorized animation of Douglass, which adds an even more realistic dimension to the moving images. They also created one with Harriet Tubman’s photos.

@Afromanticist And with Harriet Tubman (aka Araminta Ross) https://t.co/FsBlV6xLRn— Negro Montoya (@Negro Montoya)1614547595.0

Product designer Adeniyi Sonoiki also created a Harriet Tubman animation from sepia-toned photos. Amazing.

@_adeniyiS @Afromanticist @techgirl1908 THIS IS BREATHTAKING!— Derrick Jones Lopez, PhD, JD (@Derrick Jones Lopez, PhD, JD)1614537522.0

People have responded to the animations with surprising emotion. Some have found themselves deeply moved by them. Others find the technology impressive, but also a bit disconcerting, as humanity careens toward more and more believable deep fake video technology. For the purpose of bringing pre-film-era historical figures to life like this, it’s really cool. For nefarious purposes, it raises the questions we all have about what happens when people are able to create fake videos that are indistinguishable from real ones.

Some people also shared that the moving images helped “humanize” these historical figures for them. On the one hand, that’s exactly why Frederick Douglass wanted his photos taken, so mission accomplished. On the other hand, we really shouldn’t need to see these Black icons in moving pictures in order to see their full humanity. Frederick Douglass wrote about his own life in great detail, with real stories that would shake any reasonable person’s soul. But of course, you have to have read his words to know that.

Perhaps one thing these animations will do is inspire more Americans to seek out those stories and to learn more about these people who are such an integral part of the journey of our nation. This letter Frederick Douglass wrote to Harriet Tubman after she asked him to write a recommendation letter for her is a good place to start:

Rochester, August 29, 1868

Dear Harriet:

I am glad to know that the story of your eventful life has been written by a kind lady, and that the same is soon to be published. You ask for what you do not need when you call upon me for a word of commendation. I need such words from you far more than you can need them from me, especially where your superior labors and devotion to the cause of the lately enslaved of our land are known as I know them.

The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day – you in the night. I have had the applause of the crowd and the satisfaction that comes of being approved by the multitude, while the most that you have done has been witnessed by a few trembling, scarred, and foot-sore bondmen and women, whom you have led out of the house of bondage, and whose heartfelt, “God bless you,” has been your only reward.

The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism. Excepting John Brown – of sacred memory – I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have. Much that you have done would seem improbable to those who do not know you as I know you. It is to me a great pleasure and a great privilege to bear testimony for your character and your works, and to say to those to whom you may come, that I regard you in every way truthful and trustworthy.

Your friend,

Frederick Douglass.