Though she’s been dead for nearly 70 years, Mexican artist Frida Kahlo is famous around the world. She is best known for her colorful self-portraits, her bold artistic statements involving pain and passion, and her feminist activism. She is more easily recognizable than most visual artists, thanks to her own face being her main subject matter and the unibrow that served as her most prominent identifying feature. She is, in fact, arguably more well-known than her mural artist husband, Diego Rivera, who is famous in his own right.

That has not always been the case, however.

Diego Rivera was one of the most well-known artists of the early 20th century, his large-scale murals launching a revival of fresco painting in Latin America. He earned a place in a prestigious art academy in Mexico at age 10, went on to study in Spain, then settled for more than a decade in Paris. Rivera was friends with Pablo Picasso, and he lived in the U.S. for a handful of years. He painted some of his huge murals here, for the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco in 1931, the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1932, and Rockefeller Center in New York City in 1933.

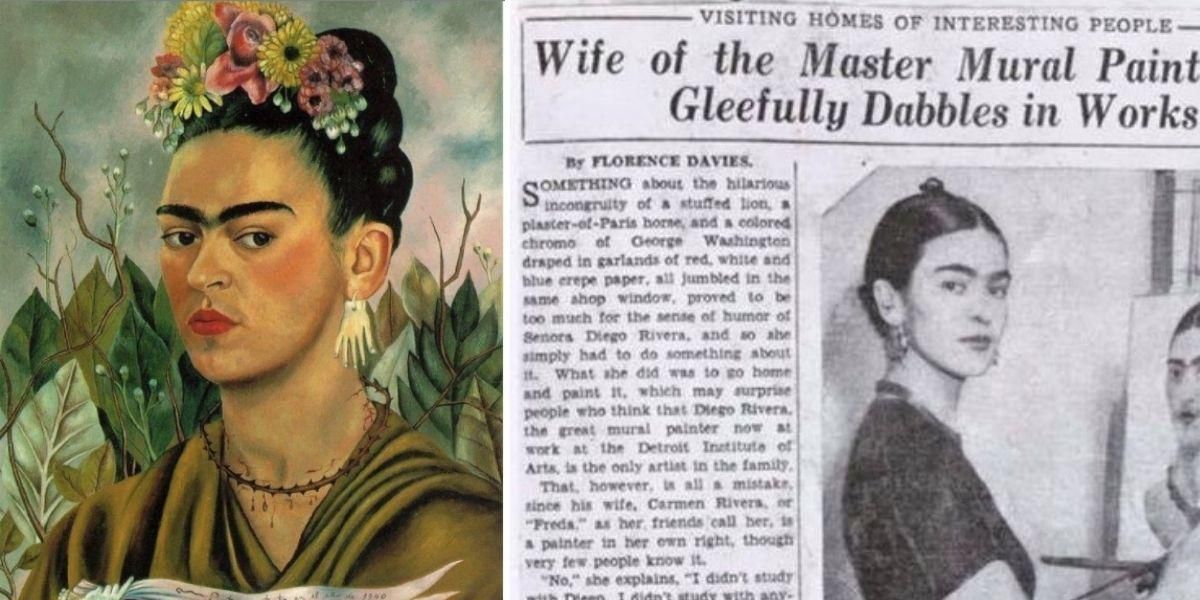

While Rivera was a household name in the 1920s and 30s, Kahlo was not, despite being a prolific artist. In fact, the headline of a 1933 Detroit News article highlighting Kahlo’s artistic endeavors referred to her simply as “wife of the master mural painter,” patronizingly describing how she “gleefully dabbles in works of art.” In hindsight, oof.

The article itself is far more gracious towards Kahlo—perhaps in part because it was written by a female writer, Florence Davies. (It’s highly likely that the headline was written by an editor, not Davies herself.)

Davies asked Kahlo if her husband had taught her to paint. “‘No, I didn’t study with Diego,” Kahlo replied. “I didn’t study with anyone. I just started to paint.'” Kahlo got a twinkle in her eye before adding, “‘Of course, he does pretty well for a little boy, but it is I who am the big artist.'” Then she exploded into laughter.

Neither Davies nor the world knew how seriously true her words would become, though Davies did describe Kahlo’s formidable talent in glowing terms.

“Senora Rivera’s painting is by no means a joke,” Davies wrote, “because, however much she may laugh when you ask her about it, the fact remains that she has acquired a very skillful and beautiful style, painting in the small with miniature-like technique, which is as far removed from the heroic figures of Rivera as could well be imagined.”

That Kahlo made a name for herself as an artist in her own right, especially in the time period in which she lived, is a testament to both her style and her spirit. Her personal story, too, is one for the ages. She was badly injured in a bus accident as a teenager and endured 35 surgeries in her short 47 years. She was married to Rivera twice—a tumultuous that was rife with infidelity. She wrote dramatic love letters and indulged heavily in drugs and alcohol. It’s hard not to be curious about such an intriguing life.

However, it’s her meteoric rise in popularity since the 1970s that has made Kahlo into a household name. Her star of fame may have emerged more gradually than Rivera’s, but it’s proven to have outshone his.

Indeed, her “dabbling” was actually the creation of a massive body of artistic work that most of us can recognize on sight. Undoubtedly that headline writer would be embarrassed now to have written about one of the world’s most famous female artists in such quaint, condescending terms. Especially when the more common question now is “Who was Diego Rivera?” with the answer being “Frida Kahlo’s husband. He was also a famous artist.”