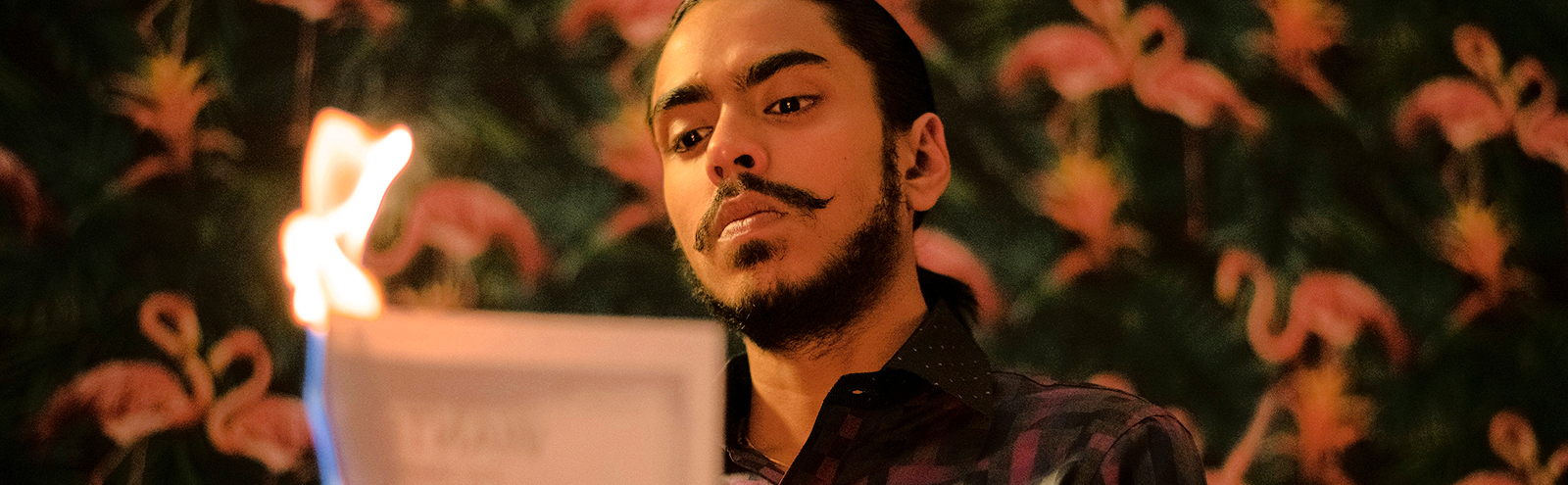

In a year of Oscar movies with star-studded casts that mostly came out in the past month or two, Ramin Bahrani’s The White Tiger was arguably the most glaring outlier, and possibly my personal favorite. Shot and set mostly in India, the film, released on Netflix in January, starred as its lead Adarsh Gourav — not only not an A-list actor, but an actor who’d never been the lead in a film before. Yet Gourav’s performance, as the striving tea shop servant writing a letter to Chinese premier Wen Jiabao, was brilliant, and this week, Bahrani, who also directed, earned his first Oscar nomination in the category of adapted screenplay.

Being the tale of lower class striver who schemes his way into a job driving for a rich man, it was impossible for The White Tiger not to invite Parasite comparisons. It’s a credit to how good The White Tiger is that it wasn’t rendered completely irrelevant by the comparison. Even more impressive, it’s a story that feels current and perfectly suited to the cultural climate, despite being adapted from a novel written by Aravind Adiga published in 2008. It feels incredibly timely despite, essentially, describing a world more than a decade past. It’s a lesson for any aspiring writer — all those specifics of time and place are what make a story universal, regardless of when and where it’s set.

I spoke to Bahrani, an Independent Spirit Award winner, Guggenheim fellow, and now Oscar nominee, about his greatest honor to date, and what it took to make the film.

—

So how honored were you to be nominated in the same category as Borat 2?

I didn’t think much about that. There are so many brilliant writers. It’s just an amazing list of names, and happy about that. It’s an amazing novel. Honestly, I feel if it was possible, they should always nominate the author of the book. I wish Aravind could be nominated too.

The novel came out in 2008. How long had you been working on it, and how did you first get involved?

Well, the author, Aravind Adiga, is a college friend of mine. So I had been reading rough drafts of the novel for four years before it was published and had been waiting 15 years to make the film. And so, it just took a while to get there, but I guess it’s been in my head for a long time. And Aravind has been reading all my screenplays and providing notes. We talk on the phone a couple of times a week, so I felt very connected to the book.

When you’re working with a friend like that, is that similar to the way you’ve made movies in the past?

Well, in fact, the big difference was Aravind always has read all my other screenplays and given his thoughts. This time, he said it would be the first time he would not read my screenplay, because he wanted me to have total freedom to do whatever I wanted. He says novel and screenplay are two different things. And he trusted me. Whatever changes or additions or subtractions, he said it was up to me. And his trust freed me, although the screenplay is pretty faithful to the tone of the novel.

In terms of the challenges, getting it made, why did it take as long as it did?

It was only four or five years ago when Aravind called me and said would I like to try to make a film of The White Tiger. And I immediately said, yes. I had always wanted to make it, but I felt it was best for him to tell me when he felt it was a good time. And he’s published four other novels now, and they’re all brilliant. In fact, I’m making another of his novels, Amnesty. I’ve set that up with Netflix to do next. Also, it just takes time for the industry to catch up, for a great company like Netflix to come around and be willing to give a sizeable amount of money to an Iranian-American director, to make a movie in India, with an entirely Indian cast, 30% in Hindi language. It’s not a small film. It’s a big, epic script. It required a lot of resources, so that was just awesome to be in the right time, at the right place for that.

And what is that like having to shoot? I assume you don’t speak Hindi yourself.

I don’t speak Hindi. I’m Iranian-American. I lived in Iran for three years, and my mother tongue is the Persian language. So I understand some words, because of there are certain Urdu words I understand in the Hindi language. What we did was, I just didn’t bring very many people with me. My crew, my department heads, who were 99% Indian, I worked very closely on the screenplay, mainly with two people. One is Mukul Deora, the producer from India, and that of course helped with all the authenticity. And my other main partner, one of the other producers is Bahareh Azimi. She’s an Iranian woman that’s been a co-writer on many of my previous films and was a producer on this film. And so, her and I have a lot of understanding of the culture, just the similarities between Iran and India.

It’s funny that it was written in 2008. I probably wasn’t the only one to compare it to Parasite, which was much more recent. What did you think about that comparison?

I do see certain parallels in terms of rich and poor and a character in a poor position trying to overwhelm the rich. Yeah. Of course. Aravind’s novel came out, I guess, 13 years ago, so it had been sitting there for a while, won the Man Booker Prize, I think it sold four or five million copies around the world, so it’s a pretty popular book. And I think there are certain similarities, and I liked the film very much, Parasite.

And then your lead actor, this was his first leading role, wasn’t it?

Yes. Oh yes. He’s a great actor, full scholarship to the best acting school in India. He had done some supporting roles in India, in fact, with some directors I like, but this was his first leading role and his first major role. And I really wanted to cast a local. All my cast is from India, and I wanted him to be from India, and he just amazed me every day. He’s just such an inspiring, talented young man, I mean, who really dedicated himself to the role, to the part, lived in a village for a few weeks to get himself into the character, worked in a teashop in Delhi for several weeks, to understand what it means to become invisible, to be part of that kind of servant class.

With the movie being set in India and being an Indian story, do you think you were playing against what people’s expectations are of a movie set in India?

To some degree, maybe, yeah. I mean, I think Aravind’s novel did that. I don’t really know of other books that are about a servant in India. So the foundation of what his brilliant novel that he provided already made the movie different, so that really helped. And then you’re always trying to subvert or upend expectations of what people think. There’s something very modern about the story and very modern about the character.

What were the key events during the production? What had to come together, where you started to realize like, “Okay, this movie is actually going to happen.”?

The biggest thing was getting Netflix, after I had written four drafts of the screenplay, was convincing Netflix to send me to India on a research, casting, location scouting, trip on my own. For them to send me out there and spend money to fly me there and give me a couple of months on the ground and to start to find actors and locations and meet people and research. When they did that, I had a feeling the movie was going to get made. And it was after that trip that I came back and they greenlit the film.

When you do that, did you have to find people to be fixers? What was that process like?

Oh yeah, yeah. It was working with Mukul Deora, my producing partner there in India. He’s a great partner. Together, we found an excellent production company that had done a lot of really good movies, so that they could build a budget and help navigate the production. It was an incredible casting director, Tess Joseph, who’s in fact, part of the Academy herself. She’s the best casting director in India and a wonderful, talented woman there. Finding her and finding a location manager. Those are the three things I did before I actually arrived in India and along with Mukul’s help. And so, when we got there, we had those people. In between scouting and casting, I was on the ground, just researching, meeting people, traveling to all the locations written in the novel. Even if they were not in the script, I just went to everywhere in the novel and tried to meet as many people as I could and interact, to try to gain as much on the ground experience as I could.

In terms of the story, the novel came out in 2008, did you play with different time periods, either trying to make it exactly now? I mean, there’s a very specific time period in which the actual movie takes place.

Yeah. The novel came out in 2008. It was probably written in the two, three years proceeding 2008, and that was a very specific time for India. It was a really booming country. The whole world was looking at India and China as the next global economic superpowers. So there was a lot of confidence in India, there was a lot of change. It was the beginning of the tech boom. And for a while, we talked about what would it be like if it was set in contemporary time, but there was something very specific about that time period in India that we wanted to capture.

Then that also led to some awesome songs. Our soundtrack was pretty time-specific, like there “Beware of the Boys,” the opening track with Panjabi MC, featuring Jay Z. That track, or Gorillaz or Fat Joe. We were able to find these awesome songs from that era to really give the film some life and feeling of the time.

If you were trying to update it to now, would you be able to do it? What things would be different?

Yeah, you could. It would have changed. He probably would not be emailing Wen Jiabao in China, because Wen Jiabao was no longer the premier, but he probably would have been, I guess, sending him Instagram stories or video messages, which for a while seemed kind of interesting. But ultimately, we wanted to keep it in that same area, for the reasons I mentioned. Also, all those drivers, they wouldn’t have been interacting with each other. It would have been more what I saw when I went to India, which is most of the drivers, instead of hanging out, telling vulgar jokes and playing cards, what they are doing in the movie and in the novel, they were mainly sitting on their own, staring into their phone. I’m not saying it’s good or bad, but it didn’t have the same flavor, or the same feeling. You know?

And all of Ashok’s ambitions had already come and gone, in terms of technology and the Internet, and the idea of the middle-class wising up. That story was over by the time it gets to 2020 in India. That movement had already started and happened, getting back to when the novel came out.

When you say came and gone, what structurally sort of changed there?

Well, there was a pretty decent economic boom. There was a change in the growth of the middle class in India. Of course, issues of poverty are still present, like all over the world. Issues of wealth inequality are global issues. I think that’s part of what I think has resonated with people around the world, Because with Netflix and this movie, it was quite a global film. I think it was seen by over 60 million people in 28 days. It was number one, I think, in 64 countries around the world. And I think part of the reason is issues of wealth inequality has made the idea of a servant class, even if it’s not called that, quite visible in many countries. In the U.S., we call our servant class Uber driver, or Seamless delivery person, or TaskRabbit worker who shows up and puts together your Ikea table. So we have that here too, we just don’t call it servant.

Right. Do you think the pandemic made that clearer and made that more visible and obvious in that way?

Unfortunately, it did, yeah. Scott Stuber at Netflix always felt that the film had a global potential, for the reasons we discussed, when he saw the first cut of the movie in April, right when we had all gone into lockdown. He was the first person, actually. I wasn’t thinking about it. He recognized that, in a sad way, the movie was going to be more relatable to people due to what was going on with the pandemic, yeah.

That was kind of my first reaction when I saw it, was that it felt incredibly current. I didn’t know about the book, so it was surprising that it was based on something that had been written so many years earlier.

What was so interesting was that when the novel came out, the financial crisis happened in 2008. And then when the movie came out, the pandemic happened. So weirdly, the movie and the novel, their releases into the world were also met with terrible… in one case, economic devastation, and in the other, economic and health devastation globally, strangely.

In keeping your setting so specific to time and place, do you think that specificity sort of makes it translate?

I think for any writer, all writers know specificity is one of the keys. The more specific you are to time, culture, place, character, the more chance you have at telling a universal story.

‘The White Tiger’ is available now on Netflix.