Since March of 2020, over 29 million Americans have been diagnosed with COVID-19, according to the CDC. Over 540,000 have died in the United States as this unprecedented pandemic has swept the globe. And yet, by the end of 2020, it looked like science was winning: vaccines had been developed.

In celebration of the power of science we spoke to three people: an individual, a medical provider, and a vaccine scientist about how vaccines have impacted them throughout their lives. Here are their answers:

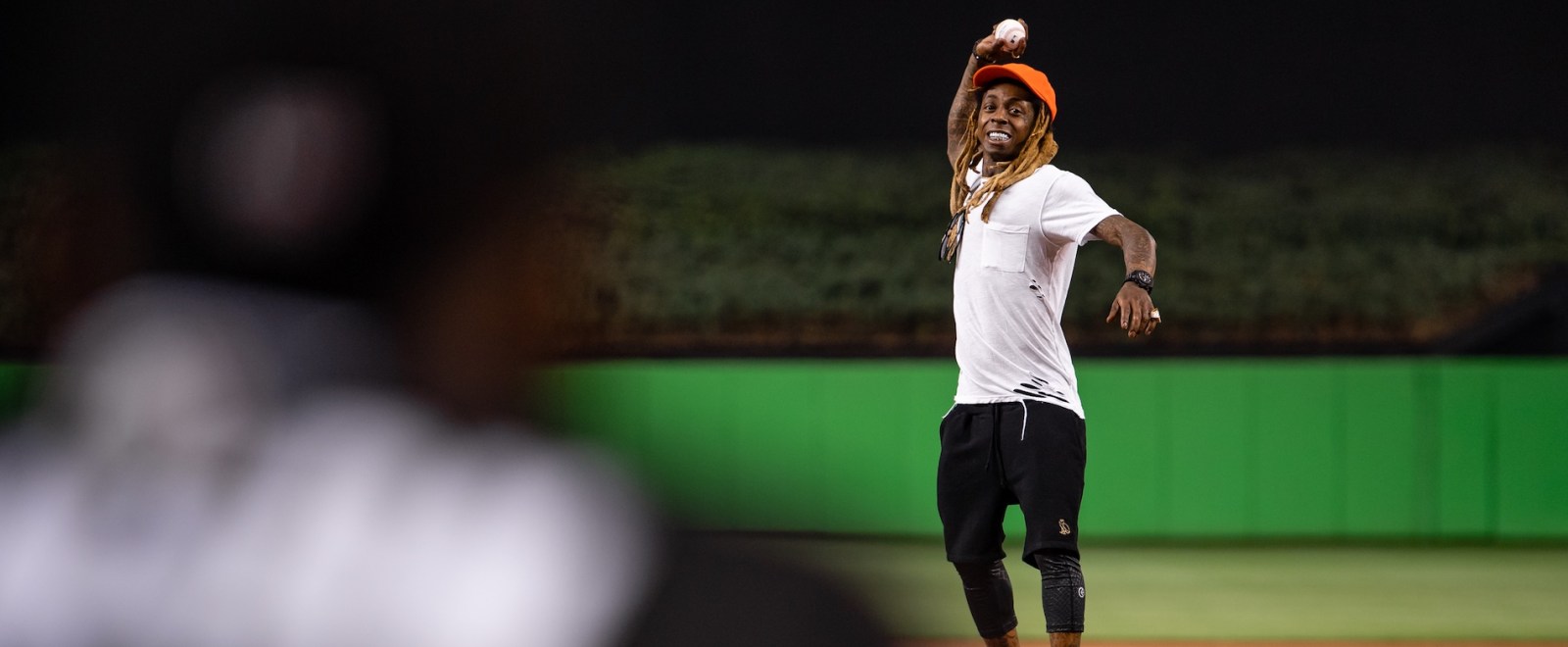

John Scully, 79, resident of Florida

![]() Photo courtesy of John Scully

Photo courtesy of John Scully

When John Scully was born, America was in the midst of an epidemic: tens of thousands of children in the United States were falling ill with paralytic poliomyelitis — otherwise known as polio, a disease that attacks the central nervous system and often leaves its victims partially or fully paralyzed.

“As kids, we were all afraid of getting polio,” he says, “because if you got polio, you could end up in the dreaded iron lung and we were all terrified of those.” Iron lungs were respirators that enclosed most of a person’s body, and which people with severe cases would end up in as they fought for their lives.

John remembers going to see matinee showings of cowboy movies on Saturdays and, before the movie, shorts would run. “Usually they showed the news,” he says, “but I just remember seeing this one clip warning us about Polio and it just showed all these kids in iron lungs.” If kids survived the iron lung, they’d often come back to school on crutches, in leg braces, or in wheelchairs.

“We all tried to be really careful in the summer — or, as we called it back then, ‘polio season,'” John says. This was because every year around Memorial Day, major outbreaks would begin to emerge and they’d spike sometime around August. People weren’t really sure how the disease spread at the time, but many believed it traveled through the water. There was no cure — and every child was susceptible to getting sick with it.

“We couldn’t swim in hot weather,” he remembers,” and the municipal outdoor pool would close down in August.”

Then, in 1954 clinical trials began for Dr. Jonas Salk’s vaccine against polio and within a year, his vaccine was announced safe. “I got that vaccine at school,” John says. Within two years, U.S. polio cases had dropped 85-95 percent — even before a second vaccine was developed by Dr. Albert Sabin in the 1960s. “I remember how much better things got after the vaccines came out. They changed everything,” John says.

In March of 2020, the world shut down because the coronavirus pandemic was raging across the country and the world. Once again, people didn’t know much about the virus — and they didn’t really know how to keep themselves safe, except to just lock themselves in their homes and avoid other people, so John and his wife hunkered down in their Florida condo, miles away from their children.

“The most challenging aspect of the shutdown was just the feeling of helplessness,” he says, especially as the pandemic began to take a toll on his family.

“My son’s a pilot and hasn’t been able to fly since the lockdowns started,” he says “My daughter and her husband had to work from home while taking care of their 9-month old baby because their daycare had shut down. Then later, both lost their jobs.”

The hardest thing, though, was being unable to visit his mother, who was 104 and living in Minnesota in an assisted living facility for all of 2020. They talked on the phone every day, though, to help her cope with the isolation but it took a toll on her. By January of 2021, her eyesight had deteriorated, she had a few bad falls, and it was clear she needed extra care. So he and his siblings made the decision to move her into a nursing home.

Within a week, she was diagnosed with COVID-19 and she died on January 30 after a 10-day battle with the virus. “I was angry when my mother got COVID,” he says, “because it felt like massive incompetence. Over 100 residents and staff got COVID in the facility where she died.”

It hurt too that this loss came around the same time as hope seemed to be in sight: Vaccines had arrived and he and his wife were eligible. They got their shots at a drive-thru site. He celebrated by seeing his grandson — who was now 21 months old — for the first time since December of 2019. “We got to be there for his first swimming lesson in our pool,” he says.

For John, his experiences living through both the polio epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic in his lifetime have driven home the importance of vaccines for public health. “I am much less worried than I was in 2020, and I am becoming more optimistic as the success of the vaccine effort is being realized, but I am still concerned about how many will resist getting the vaccination,” John says. “And I’m worried about the viruses out there that we don’t know about.”

“But I’m confident science can find a way,” he adds. “I’m hopeful for the future.”

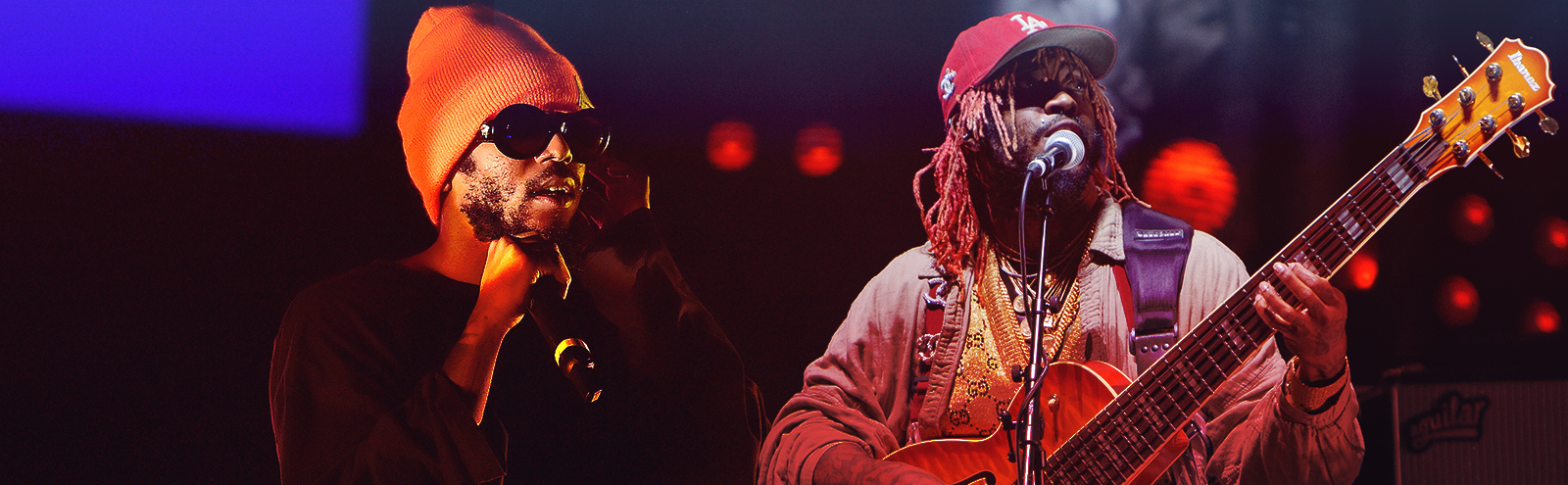

Dr. Alvin Cantero, nurse practitioner and CEO of Alvin Clinica Familiar in Houston, Texas

![]() Photo provided by Walden University

Photo provided by Walden University

Dr. Alvin Cantero has always wanted to help others. He had been a physician in his native Cuba and, after immigrating to the United States in 2009, he decided to get his degree in nursing practice to provide for his family back home. He also wanted to help underserved communities, so while he was working towards his master’s in nursing science and doctoral degree in nursing practice at Walden University, he opened a clinic in a Hispanic and African neighborhood of Houston, Texas.

“The aim was to provide quality care to underserved people, like the homeless, veterans, immigrants, refugees, and all the people who don’t have enough resources to find other care,” he says.

When the pandemic hit Houston, a number of clinics like his shut down. But he refused to shut his doors. He knew his patients didn’t have anywhere else to go.

“A lot of my patients got very scared. They had nowhere to go and they started getting infected after believing that the pandemic was just like the typical flu or a cold,” he says. “Then, when people started dying, they got even more scared.”

“My patients increased from 10 to 15 patients a day to 50-60 a day,” he continues.

“I offer my clinic as a shelter for those patients,” he says. And in the process, he says, he fulfills an important role when he gains their trust: he helps educate them about the importance of preventative care while combating misinformation about science, healthcare, and the role of vaccines in keeping people safe.

He first encountered this kind of misinformation when he was working on his doctoral thesis on Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines at Walden University. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States, which can lead to six types of cancers later in life. He encountered a number of parents that were hesitant to administer the vaccine to their children. “They were afraid it would induce early sexual relationships,” he says, “or have negative psychological effects.”

This experience with vaccine hesitancy, he says, was invaluable in helping shape how he would later approach educational efforts about preventative care with his patients at his clinic — especially after the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines.

“I have some patients that told me they don’t want the [COVID-19] vaccination because they heard things that aren’t right,” he says, “They believed a lot of conspiracy theories.”

So he does what he can to educate them — which begins by telling them why he got vaccinated, himself. “I tell them, I have to protect you, I have to protect my family, I have to protect my community, so I got the vaccine” he explains. “I show them my vaccination card and then I explain about the benefits of vaccination and why the conspiracy theories are not true.”

“You cannot be pushy,” he continues. “You have to be patient. You have to do it through family intervention and you also have to do it through the community.” That’s why, Alvin says, he regularly goes to the YMCA and local churches to speak about the importance of vaccines.

“Vaccinations are a very important part of preventative care nationwide and we still have a long way to go in educating the population and discontinuing the spread of misleading information that has no scientific basis,” he says. That’s why it’s important to “work closely with community leaders who can help us change negative perceptions of vaccines within underserved communities. This can prevent further outbreaks of preventable diseases, such as measles.”

So far, Alvin is optimistic that the future of medicine will see less fear around vaccines. “More patients and families are coming into my practice seeking help and guidance to register for their COVID-19 vaccinations,” he says, “and they’re also inquiring about continuing regular immunization schedules for their children and teenagers.”

“I’m very optimistic,” he continues, when asked whether he thinks these educational efforts will pay off post-pandemic. “There will be a huge positive change in primary care moving forward.”

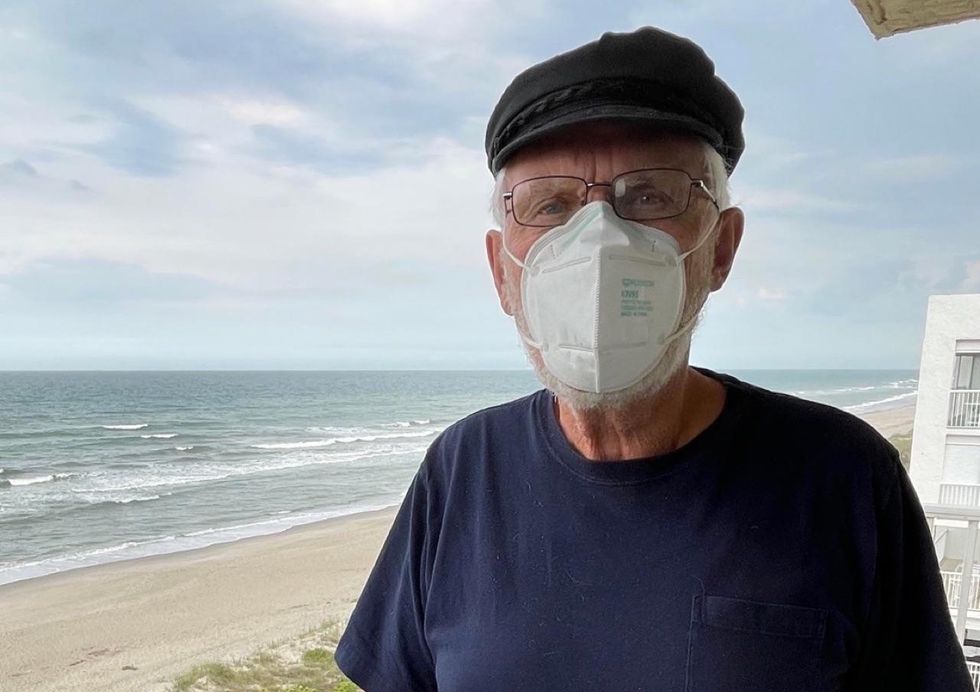

Ingrid Lea Scully, Pfizer Scientist specializing in immunology

![]() Photo courtesy of Ingrid Lea Scully

Photo courtesy of Ingrid Lea Scully

Pfizer scientist Ingrid Lea Scully (no relation to John Scully) has never doubted the importance of vaccines.

“To paraphrase a great scientist in the field of vaccines, after the provision of safe drinking water, vaccines have had the greatest impact on human health,” she says.

In fact, this is part of why Ingrid went to work in vaccine research and development after her postdoctoral fellowship.

“I have always loved the natural world and we watched a lot of PBS at home,” she says. “My grandparents bought me National Geographic books, and I would memorize facts about different animals.” Later in life, educators helped continue to foster her love for science, including one who introduced her to immunology, the study of the immune system.

“What I loved most about immunology is that everything is connected,” she says.

Ingrid has been working at Pfizer for 16 years now. “I lead teams that develop tests to see if the vaccines we are developing ‘work,’ — whether the vaccines cause the body to make an immune response that ‘kills’ the germ, or pathogen,” she says. “We are trying to understand what immune response patterns correlate with protection against a given pathogen.”

“The ultimate goal is to be able to predict whether a vaccine will be protective early on in development, and to be able to tailor the immune response to a pathogen and to a certain population,” she continues. “One exciting new application is the development of vaccines for pregnant women, to protect their newborn babies from disease, like respiratory syncytial virus, which makes it hard to breathe, and group B streptococcus, which causes sepsis in newborns.”

In addition, she says, “I’m very excited about our ability to harness mRNA technology for vaccines. This is a very flexible platform that has the potential to revolutionize vaccines.”

For Ingrid, the most exciting moment in her career has been working on the COVID-19 vaccine — and being a part of a critical rollout. “[It’s] humbling, exhilarating, exhausting. Maybe not in that order,” she says.

“We’ve seen this past year what a profound impact infectious disease can have on everyday lives, how much energy is required to stay safe,” she continues. “We have not seen so clearly the impact of what we do as we have in the past year. It drives us on.”

That’s why she’s confident that science will win — and make the world better by improving human health.

“I hope that the silver lining of the pandemic is that more young people, from all backgrounds, will choose to become scientists,” Ingrid says. “The best thing in the world was when my 6-year-old daughter told me, ‘Mama, I’m so proud of you. You’re beating the virus.'”

That gives her hope.

“When we put our minds to it, we are empowered through science to find the solution to healthcare problems,” she says. “There are thousands of dedicated scientists working on vaccines. We do this job because we want to make the world a better place. To save the lives of babies and grandparents around the world. To unlock human potential by reducing disease.”

*Editorial Note: John Scully is the author’s father.

Photo courtesy of John Scully

Photo courtesy of John Scully Photo provided by Walden University

Photo provided by Walden University Photo courtesy of Ingrid Lea Scully

Photo courtesy of Ingrid Lea Scully