If you were to meet my college-aged daughter on certain days, you’d never guess she suffered from a debilitating anxiety disorder. She can be personable, she can appear confident, she can seem at ease and comfortable in her own skin from the outside. She’s a musician and she performs beautifully—and even particularly well under pressure. You might catch her belly laughing with her friends. You might see her excel at giving a class presentation. You might marvel at her many gifts.

What you wouldn’t see is how many days she has spent barely able to leave her bedroom. How many hours she’s spent paralyzed by the “what if” monster in her brain. How many social events she’s missed because she just couldn’t make herself get in the car. How many emails she’s had to send teachers to explain that her anxiety was getting the better of her (and could she possibly get an extension on a deadline?). You won’t see how many times and ways she’s beat herself up for not being able to function like people who don’t struggle with mental illness.

My daughter is smart and talented and capable. She also wages daily internal battles most people don’t see, and she doesn’t win every battle. Therapy has helped a lot, but it’s a lot of work. Raising her has helped me develop a deep respect for anyone who struggles with anxiety because I know how much work it takes to get to a good place. And I know how much work it takes to get your brain to stay there.

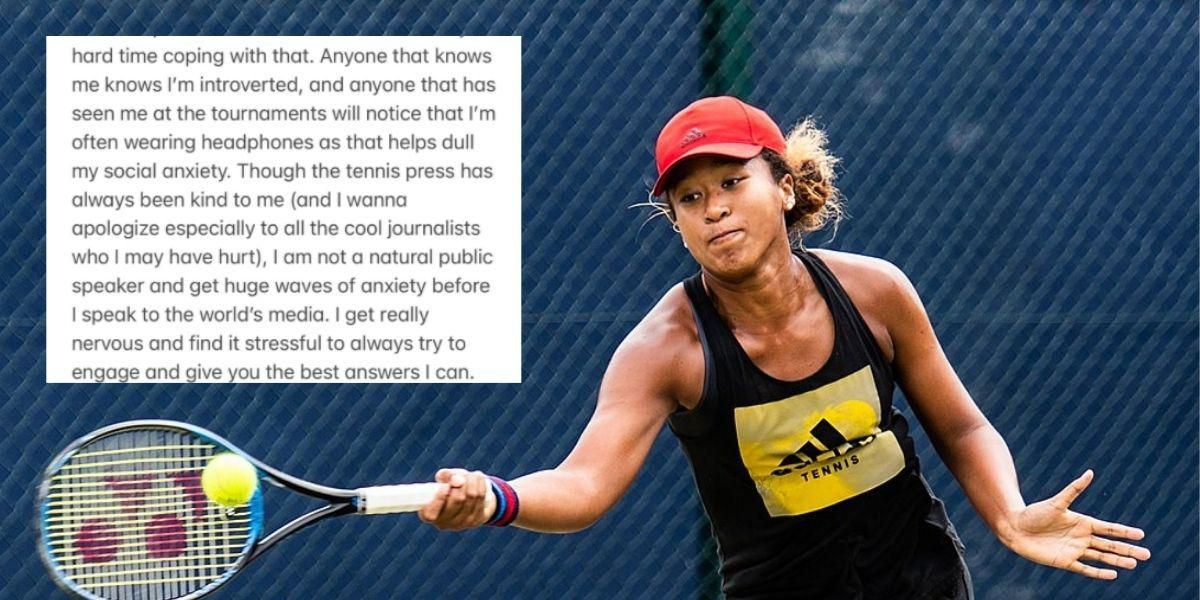

That’s why seeing tennis star Naomi Osaka announce that she wasn’t going to do press conferences at the French Open because they were too hard on her mental health piqued my attention. I don’t really follow tennis and only know Osaka’s name from headlines, but reading her initial statement felt familiar.

At age 23, Osaka is only a few years older than my daughter. And yet it’s clear that she, like my daughter, has learned to advocate for herself. That’s a gift that should not be undervalued.

When Osaka explained that she wouldn’t be doing press conferences at the French Open, many people immediately criticized her. Talking to the press is part of being a professional athlete, some said, and if she doesn’t like it maybe she shouldn’t be in pro sports. I don’t think those people actually listened to what she was saying. Or perhaps they didn’t really think through what she said.

“I’ve often felt that people have no regard for athletes’ mental health and this rings very true whenever I see a press conference or partake in one,” Osaka wrote in a statement on Twitter and Instagram last week. “We’re often sat there and asked questions that we’ve been asked multiple times before or asked questions that bring doubt into our minds and I’m just not going to subject myself to people that doubt me.

“I’ve watched many clips of athletes breaking down after a loss in the press room and I know you have as well. I believe that whole situation is kicking a person while they’re down and I don’t understand the reasoning behind it.”

After basically being told she’d have to participate in press conferences, face huge fines, or perhaps be prevented from competing, Osaka pulled out of the tournament altogether. And this time, she got a bit more specific about her mental health struggles.

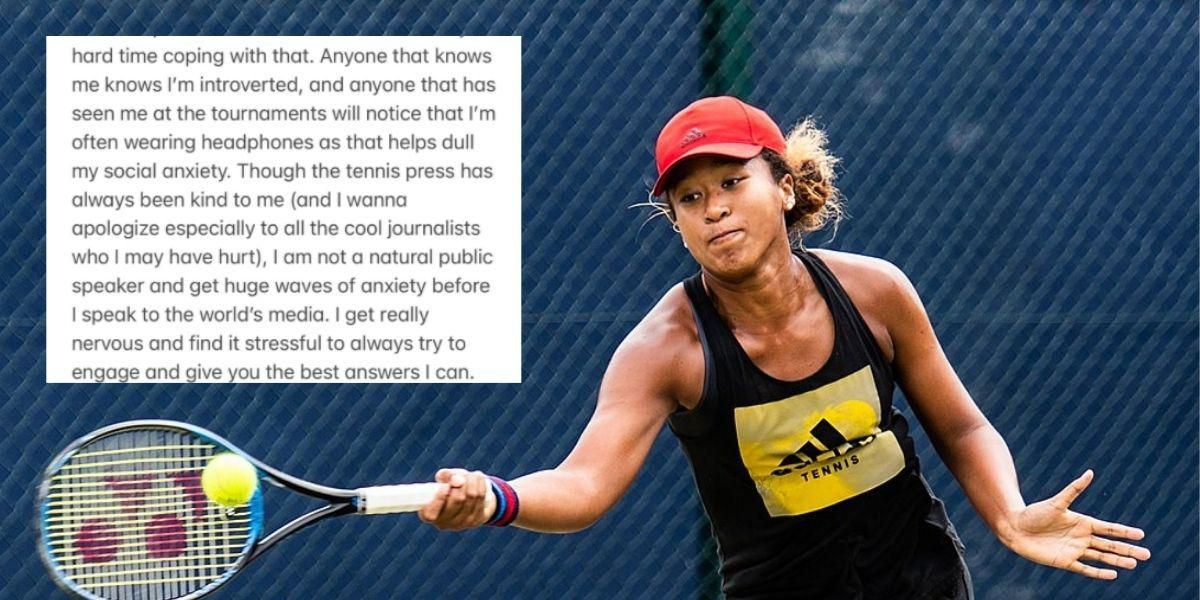

“I have suffered long bouts of depression since the US Open in 2018 and I have had a really hard time coping with that,” she wrote. “Anyone that knows me knows I’m introverted, and anyone that has seen me at the tournaments will notice that I’m often wearing headphones as that helps dull my social anxiety.

“Though the tennis press has always been kind to me (and I wanna apologize especially to all the cool journalists who I may have hurt), I am not a natural public speaker and get huge waves of anxiety before I speak to the world’s media. I get really nervous and find it stressful to always try to engage and give you the best answers I can.”

I can imagine my daughter saying something like this—and I also know that she’d mean something more than what the simple words on the page say. Most of us would feel nervous talking to the press, naturally, which leads to people’s “Eh, just suck it up and deal with it” attitudes. But for someone who struggles with anxiety as a mental health disorder, it’s not just about dealing with some nerves. Anxiety can be debilitating—and it affects everything. My daughter’s anxiety disorder has nothing directly to do with her schoolwork, and yet it makes getting her schoolwork done nearly impossible some days. I can only imagine how anxiety would impact an athlete’s performance—the whole purpose for their being in a tournament to begin with—and how necessary it would feel to mitigate the things that contribute to it.

So while some people have called Osaka a drama queen or a diva for saying, “I’m not okay with this, and here’s why,” I see a young woman who is being vulnerable in sharing her needs, advocating for herself, and taking necessary action when a situation isn’t tenable.

My daughter has had to learn to advocate for herself, which is vulnerable and scary. Thankfully, the vast majority of the time her self-advocacy been met with support and reasonable accommodation. I’ve seen similar support and solidarity pour out for Osaka on social media, which is heartening. I’ve also seen callous criticism and cruelty, which heartbreaking.

Naomi Osaka is one of the top tennis players on the planet, and for her to back out of a major global tournament is no small thing. And she’s right—talking to the press isn’t an innate part of being an athlete, nor is it a necessary one, especially in the age of social media where athletes have the ability to speak directly to people who follow them.

I’ve seen people bag on Osaka because she makes millions of dollars from tennis, meaning she should just put up with the bad stuff since it’s paying her so well. But just because someone is highly successful in their field and makes a ton of money doesn’t mean they are immune to mental health issues, and it certainly doesn’t mean we should expect them to do things that are hurting them.

When my daughter is deep in a bout of anxiety, no amount of money could make her do something that her brain is telling her not to do—even when it’s something she wants to do. But that doesn’t mean she can’t do anything. Naomi Osaka’s mental health isn’t keeping her from playing tennis. Her ability to compete isn’t the question here. It’s the mental health impact of media expectations, and if an athlete who is at the top of their game, who has spent their whole life working toward competing in top-level tournaments, backs out of something like the French Open, that means something.

Having watched and walked with my daughter through years of battle with her own brain, I admire Osaka for highlighting the importance of mental health. I know that many people don’t understand her needs or don’t agree with the way she’s communicating them, but those people have no idea how hard this stuff is. Seriously, no idea.

I know, because I didn’t have any idea until I witnessed and walked with my daughter through her own anxiety ups and downs how hard it truly is. So even if the only thing that comes from this is a bigger discussion on mental health, great. We need to talk about this stuff more often and more openly.

Thank you, Ms. Osaka, for getting the ball rolling.

(@Sha_Elise24) June 1, 2021

(@cmclymer) June 1, 2021