This article originally appeared on 12.06.16

When the attack on Pearl Harbor began, Doris “Dorie” Miller was working laundry duty on the USS West Virginia.

He’d enlisted in the Navy at age 19 to explore life outside of Waco, Texas, and to make some extra money for his family. But the Navy was segregated at the time, so Miller, an African-American, and other sailors of color like him weren’t allowed to serve in combat positions. Instead, they worked as cooks, stewards, cabin boys, and mess attendants. They received no weapons training and were prohibited from firing guns.

As the first torpedoes fell, Dorie Miller had an impossible choice: follow the rules or help defend the ship?

For Miller, the choice was obvious.

USS West Virginia and USS Tennessee surrounded in smoke and flames following the surprise attack by Japanese forces. Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Archive and Records Administration.

First, he reportedly carried wounded sailors to safety, including his own captain. But there was more to be done.

In the heat of the aerial attack, Miller saw an abandoned Browning .50 caliber anti-aircraft machine gun on deck and immediately decided to fly in the face of segregation and military rules to help defend his ship and country.

Though he had no training, he manned the weapon and shot at the enemy aircraft until his gun ran out of ammunition, potentially downing as many as six Japanese planes. In the melee, even Miller himself didn’t know his effort was successful.

“It wasn’t hard,” he said after the battle. “I just pulled the trigger and she worked fine. I had watched the others with these guns. I guess I fired her for about 15 minutes. I think I got one of those [Japanese] planes. They were diving pretty close to us.”

Image courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Original newspaper reports heralded a hero “Negro messman” at Pearl Harbor, but no one knew who Miller was.

The Pittsburgh Courier, an African-American paper in wide circulation, sent a reporter to track down and identify the brave sailor, but it took months of digging to uncover the messman’s identity.

Eventually, Miller was identified. He was called a hero by Americans of all stripes and colors. He appeared on radio shows and became a celebrity in his own right.

Doris “Dorie” Miller. Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Miller’s heroism and bravery didn’t go unnoticed in Washington, D.C., either.

In March 1942, Rep. John Dingell, a Democrat from Michigan, introduced a bill authorizing the president to present Miller with the Congressional Medal of Honor. Sen. James Mead introduced a similar measure in the Senate. While Miller did not receive the Congressional Medal of Honor, he became the first African-American sailor to receive the Navy Cross.

“This marks the first time in this conflict that such high tribute has been made in the Pacific Fleet to a member of his race, and I’m sure that the future will see others similarly honored for brave acts,” said Pacific Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz following Miller’s pinning ceremony.

Miller receiving the Navy Cross from Admiral Nimitz. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Following a brief tour of the country, giving speeches and pushing war bonds, Miller returned to Navy life.

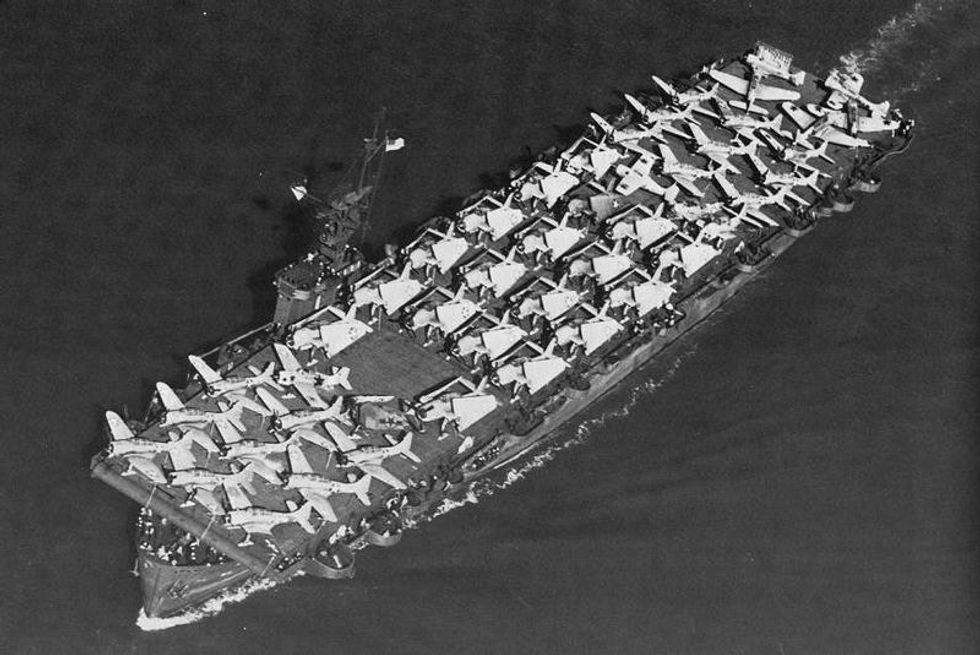

In May 1943, Miller reported for duty on the Liscome Bay, an escort carrier.

The USS Liscome Bay prepares for action.

On Nov. 24, during Operation Galvanic, a Japanese torpedo struck the Liscome Bay, sinking the ship. 644 men were presumed dead. 272 survived. Miller did not.

On Dec. 7, 1943, two years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Millers’ parents received word of their son’s death.

Doris “Dorie” Miller gave his life for a country that didn’t always love him back.

Miller posthumously received a Purple Heart, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, the American Defense Service Medal, Fleet Clasp, and the World War II Victory Medal. There is also a frigate and a neighborhood on the U.S. Naval Base in Pearl Harbor named in his honor.

Though his Navy Cross was never elevated to a Congressional Medal of Honor, as recently as 2014, the Congressional Black Caucus moved to waive the statute of limitations to make it possible.

Image courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administrations.

While there are medals, movies, and statues celebrating Miller, it’s important to remember and honor the man himself — a 22-year-old black sailor who set aside the rules to do what’s right.

Poet Gwendolyn Brooks wrote a poem from Miller’s perspective, the conclusion of which perfectly captures the young hero’s courage in the face of bigotry and uncertainty:

Naturally, the important thing is, I helped to save them,

them and a part of their democracy,

Even if I had to kick their law into their teeth in order to do that for them.

And I am feeling well and settled in myself because I believe it was a good job,

Despite this possible horror: that they might prefer the

Preservation of their law in all its sick dignity and their knives

To the continuation of their creed

And their lives.