This article originally appeared on 04.26.16

On April 26, 1986, the world experienced the worst ever nuclear disaster.

It occurred at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, located in Ukraine. Immediately after the meltdown, dozens died. 30 years later, the number of lives lost to the plant’s radiation lies somewhere in the tens of thousands.

If not for the work of three brave men, we may have lost millions of lives instead.

The plant, severely damaged, four days after the disaster. Photo by AFP/Getty Images.

10 days after the Chernobyl meltdown, engineers learned of a new threat: nuclear steam explosions.

The plant’s water-cooling system had failed, and a pool had formed directly under the highly radioactive reactor. With no cooling, it was just going to be a matter of time before a lava-like substance melted through the remaining barriers, dropping the reactor’s core into the pool. If this would have happened, it might have set off steam explosions, firing radiation high and wide into the sky, spreading across parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa.

“Our experts studied the possibility and concluded that the explosion would have had a force of three to five megatons,” said Soviet physicist Vassili Nesterenko. “Minsk, which is 320 kilometers from Chernobyl, would have been razed and Europe rendered uninhabitable.”

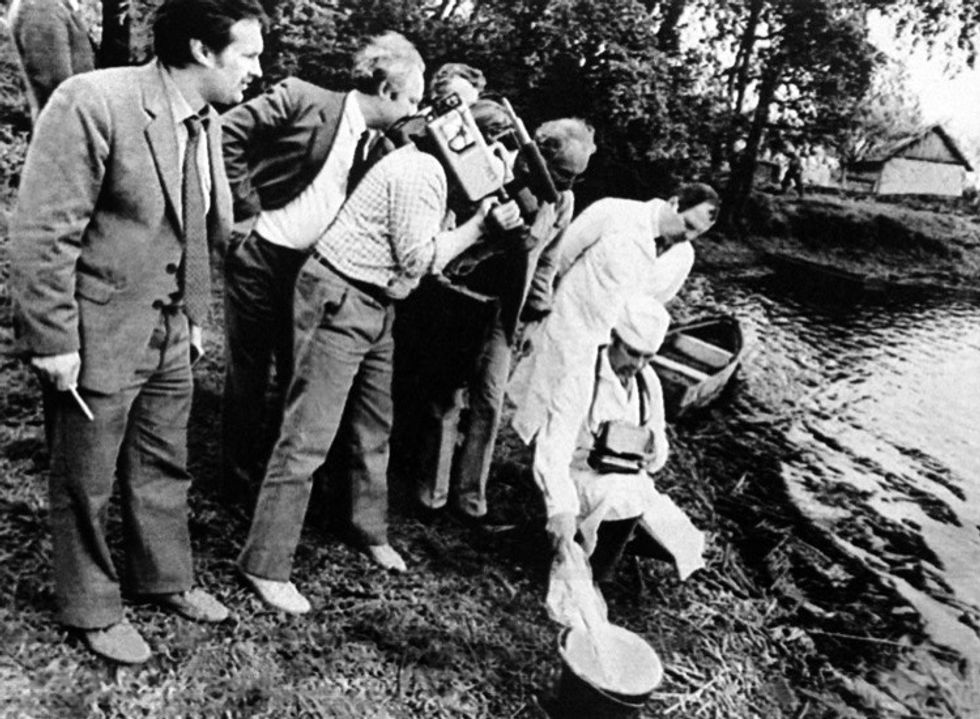

Soviet engineers test waters for radiation within the 30-kilometer “forbidden zone.” Photo by AFP/Getty Images.

Three brave men volunteered to dive under the plant and release a critical pressure valve.

Just one available man knew the location of the release valve. His name was Alexei Ananenko, and he was one of the plant’s engineers. He along with fellow engineer Valeri Bezpalov and shift supervisor Boris Baranov were asked to take on what amounted to a suicide mission.

The men were told they could refuse the assignment, but Ananenko later said, “How could I do that when I was the only person on the shift who knew where the valves were located?”

Decades after the disaster, a visitor photographs a memorial built for the first responders of Chernobyl. Photo by Sergei Supinsky/AFP/Getty Images.

The men released the valve in time and, in doing so, saved the world from a disaster that would have been exponentially worse than the initial explosion.

Over the following days, more than 5 million gallons of water were released from below the plant. A report later confirmed that without the work of Ananeko, Bezpalov, and Baranov, a nuclear explosion would have taken place, turning hundreds of square miles into an inhabitable radioactive wasteland.

A nuclear hazard warning is seen in Kopachi, one of the many villages close to the Chernobyl plant buried after the disaster to reduce the spread of radiation. Photo by Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images.

By the time the men surfaced from under the reactor, all three were showing signs of severe radiation poisoning. Tragically, none of them survived for more than a few weeks.

Like other victims of the Chernobyl disaster, the three men were buried in lead coffins.

What makes their actions unique in comparison to those of the disaster’s first responders is that these men were warned outright of the danger radiation posed — firefighters weren’t given any background on radiation poisoning before running to put out the flames. They’re all heroes, but these three men knew they’d die; they did it anyway, saving the lives of hundreds of thousands.

Their story has been mostly lost to time, with references only popping up in books about catastrophe, danger, and disaster. But the names of these three men shouldn’t be forgotten.

A monument is dedicated to the lives of all those lost in the Chernobyl disaster. Photo by Boris Cambreleng/AFP/Getty Images.

Alexei Ananenko, Valeri Bezpalov, and Boris Baranov didn’t prevent the Chernobyl disaster; they prevented something much, much worse.

Their story really makes you think about the label “hero.” For some, like the three Chernobyl divers, heroics come quietly as the result of a quashed threat. For others, like the first responders at Chernobyl or Fukushima, during 9/11, or in response to other terrorist attacks, heroics are the result of running toward danger so that others may run away from it.

The truth is that heroes are all around us. Teachers, health care workers, and just everyday people are and have the capacity to be heroes in their own right. No capes needed, just a little faith in the human spirit.