Along with the Alice Cooper song people cinematically channel in their minds when they need to tell someone where to go, ‘No More Mr. Nice Guy’ can be a kind of initiating affectation into the NBA. Players shed the genial or wide-eyed parts of themselves when entering the league and adopt competitive personas that trade chummy for cut-throat, the logic being that a winning mentality must also be inherently ruthless. The culture of competitive sports has historically placed a high value on athletes who, more than present as unrelenting in their drive and focus, skew savage, and for the progressive shifts it has made in the game’s overall culture, the NBA as a league still tends to favor that mentality. Case in point, when you see the word ‘mentality’ in relation to basketball, you’ve already subconsciously slipped a ‘mamba’ in front of it.

It’s become an almost lazy shorthand as much as an ironic one — people not knowing so and so was a bucket, someone else being built different, a long and never-ending string of the steam nose emojis — a behavioral fallback that, if the NBA Finals and the Finals MVP that emerged from them can be seen as a barometer, might finally see its maniacal, blowhard grip loosening.

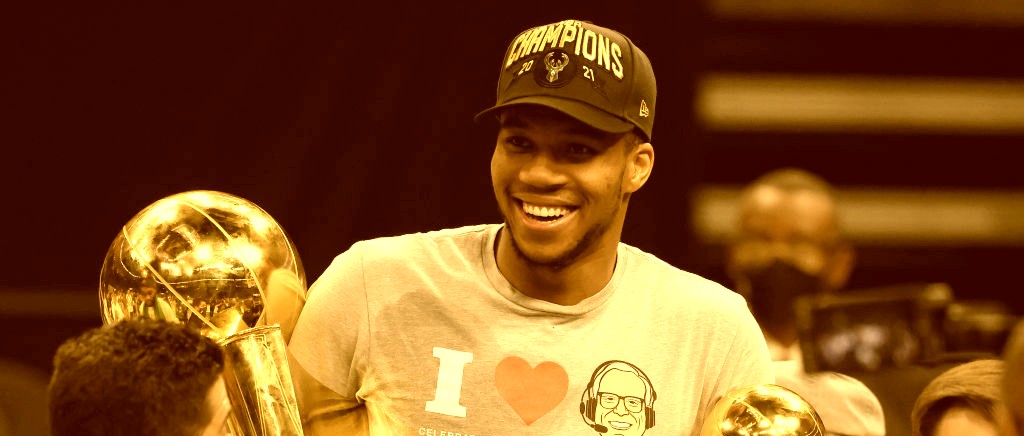

Giannis Antetokounmpo is nice. Not just polite, or easy to coach, not just friendly to fans and the media, but nice nice. Taken aback when a girl nervously hands him a folder with a year’s worth of art projects in it about him nice. Nice in a way that is so natural and unselfconscious that it feels like an understatement to phrase it in such a comparatively diminutive four-letter word.

And none of his kindness has come at the cost of his competitiveness. On-court, Antetokounmpo plays with a dominance he’s turned elemental. More than a juggernaut star who inhales all the minutes and touches due him, Antetokounmpo can quietly crash down on an opponent out of nowhere like a downpour on a clear day as easily as he can be the cold snap seizing the game and shattering it. Like ozone rising in the air there’s no place on court that it’s possible to escape the pressurizing feel of him. The puffed-up bodybuilder’s pose after a dunk or a chasedown, his face squished up in a sneer, these gestures play out like theatrical nods to what he understands people feel when watching him than they do an ode to any broader construct of dominance.

Instead, in Antetokounmpo there’s a refusal to “get over” the feeling that the game stirs up in him and anybody watching. That easy giddiness and joy, the simplified sense of happiness that can come at performing (and watching) astonishing feats of athleticism every night and then pushing those further. Existing at the perfect conjuncture of velocity, time and skill again and again. In a game so steeped in the domineering culture of no days off and happiness too often seen as fissures weakness might seep in through, Antetokounmpo’s rejection of growing more closed off as his career goes on, or shedding the easy and effusive glee that radiates from him on and off court, can sometimes feel refreshingly radical.

Attempting to trace the canon of similarly delighted dudes that came before him is a quick exercise, because there have been so few at the level Antetokounmpo currently sits at. Chris Bosh, maybe, in terms of outright awe that skews cheery, even goofy, or Jose Calderon for the sheer willingness and appreciation he brought to the game and the culture around it. Steph Curry has been given the label of nice guy, and no doubt has shown his knack for vaulting anyone into sudden bouts of joy like they were spontaneously launched from a trampoline, but Curry slips in and out of his happiness, changeable like a day dotted with quick moving clouds. The closest institutional player who has handled the game with the same easy reverie was Tim Duncan, his quiet kindness and unpretentious approach to the force that he could be, the friendly tide that lifted all the ships around him.

They all fall short if only because Antetokounmpo in his happiness is so wholly unguarded that it can feel like a public resource. His openness works like an invitation, we want to root for him as much as the sunnier sides of him refract back onto us. Watching the Bucks dig in and trudge forward through a season that lurched between uncomfortable to unsound, awry to occasionally cruel in its physical and mental tolls, seemed the living adage of one foot in front of the other. Seeing Milwaukee, a team of castoffs like Bobby Portis, perpetual, dogged role-players like PJ Tucker, the everyman’s everyman of Khris Middleton, get up and dust themselves off each time they took a misstep, felt buoyant and possible because of the sunny engine of Antetokounmpo driving it.

These Finals made it difficult, if not impossible, to pick a rooting interest if you didn’t live within each franchise’s state lines. It wasn’t David vs. Goliath, or two super teams meeting to determine the tighter stranglehold of league dominance, it was instead a feel-good story wherever you started from. The Suns, rising due in large part to the bedrock of trust and chemistry Monty Williams instilled in his team, were an undoubtably compelling reason, but it was the delighted, occasionally fascinated spell of Antetokounmpo that was hardest to break. In the Bucks winning it all, the takeaways of team-building over time, of a star player sticking it out giving hope to franchises that don’t have the same gravitational pull as bigger markets, of a new generation of stars getting comfortable with the big stage, are all apt. But the breezy overhaul Antetokounmpo has had a hand in doing to the league and our own expectations of what competition should and could look like, by being nice, feels particularly vital, especially coming out of a season, a year, like this one.

That he’s arrived at the top is not just a worthwhile testament to resiliency combined with an unquestionable talent and, yes, an athleticism that warps the fundamentals of physics, but a rare proof that greatness is possible without forfeiting the best and most vulnerable parts of person. That to stay open, to reject the nescient and tired tropes of what soft can be, can do, allows the space needed for the most colossal of dreams.

: danbaileymt on Instagram)

: danbaileymt on Instagram)