Wes Anderson movies: we love to rank them, don’t we, folks? It’s both one of the most hack listicles a movie writer could write, but also dishonest not to write. Sure, I could pretend I’m above it; that I’m better than ranking Wes Anderson movies, that I can simply enjoy things without assigning numbers to them. But let’s be honest, I’m 100% not above that. I’ve seen them all, I have strong opinions, and pretending otherwise would just be an affectation. KNIFE FIGHT ME, COWARDS! Meet me behind the internet at dawn.

It’s fair to say that I have a love/hate relationship with Wes Anderson movies, as I do with most things smug and overeducated (for the simple reason that I’m both but I try not to be). I get about as fed up with his precious, fussy, practiced kitsch as any inveterate Wes Anderson hater. Yet I still find myself mostly enjoying all his movies, even when parts of them press hard on my gag reflex. Once you reach a certain level of liberal arts education I believe you’re simply powerless to resist Wes Anderson’s bullshit.

Or maybe it’s that he’s usually just vulgar enough — think the vagina painting in Grand Budapest Hotel, Max Fischer bragging about handjobs — that I forgive him for being so twee, and for probably being the reason I ever learned the word “twee.” Whatever you think of him, he’s one of the most easily parodied directors working, possibly the most easily parodied director that ever lived. He wears his tics on his tweed sleeves, with an instantly recognizable style (a “shtick,” one might even call it), and a list of interests and affinities that seems to carry through all of his movies.

Having seen them all at least once, here is an incomplete list of things that Wes Anderson loves:

Mustaches

Uniforms

Warm colors

Centered frames

Mid-century modern styling

Precocious children

Yellow text

Overwrought prose

Little kids falling in love

Lists

Child-like drawings

Sons desperately trying to please emotionally withholding father figures

Precocious boys desperately trying to please female authority figures whom they are also horny for

Berets

India

France

Rascals

Hucksters

Bureaucratic jargon

Motorcycles with sidecars

Trains

Harpsichord music

German convertibles

Social clubs

Pun names

Girls with too much eye make-up

Men with interesting noses

Men with bandaged noses

Man servants

Pets

Funerals

Now then. Let’s begin:

9. The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

This was always one of my least favorite Wes Anderson movies, so I rewatched it this week to see if maybe I had been wrong about it. While there are definitely things to love, it still feels somehow both overlong and incomplete, even clocking in at barely 90 minutes.

Jason Schwartzman, Owen Wilson, and Adrien Brody (the unique nose crew, I call them) play three brothers who have come to India following the death of their father (Bill Murray, in the briefest of flashbacks) for a journey of self-discovery and also to track down their mother, played by Anjelica Huston. The Darjeeling Limited is the name of the train on which they travel.

A trip through India on a train is, visually, a perfect Wes Anderson setting: colorful, retro, and orientalist, but there’s something shallow about the whole endeavor. The scene in which the boys try to save three Indian boys from a rushing river and one of them drowns seems to confirm this shallowness. A little boy drowning as an emotional anchor for Adrien Brody’s disaffected rich guy with daddy issues? It mostly just ends up being offputting. Irrfan Khan gets 15 seconds of screentime and then the boys just sort of carry on trying to figure out their family, with a father we never really learn much about and a mother who has fled to Tibet to live at a monastery.

What the hell was the deal with that mom, anyway? It seems like Anderson may have had some kind of emotional reckoning planned but couldn’t quite make it come together. So instead we’re left delving the emotional issues of a family that feels remote and a little esoteric. I don’t quite relate and just sort of leave feeling, “Rich people sure are weird, aren’t they?”

8. Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

Moonrise Kingdom is perhaps Wes Anderson’s most mixed bag. A story about a delinquent-ish “khaki scout” who goes AWOL with a raccoon-eyed Francophile girl on the fictional New England island of “New Penzance” (always with the fucking pun names), Moonrise Kingdom is a film with a promising opening and a glorious crescendo at the end that forces us to watch a lot of pre-pubescent love in between. The ending, set amidst a massive storm as foreshadowed by The Flood, an opera the local children are staging, is so magnificent, and yet the love story it bookends feels like a Hallmark movie sponsored by Stella Artois.

Coming on the heels of The Life Aquatic, Darjeeling Limited, and Fantastic Mr. Fox, three movies that feel like Anderson doing his best to expand his repertoire, Moonrise Kingdom always felt to me like Anderson going back to the well. The story feels a little like the Royal Tenenbaums subplot where Margot and Richie run away to the museum stretched into an entire film. Only it doesn’t work as well, because Margot and Richie we knew as adults. Sam and Suzy are just two little kids.

And yet… those actors. That setting. The ending. It’s hard to hate entirely. Wes Anderson’s ability to stage a genuinely heartfelt finale always saves him in the end.

7. Isle Of Dogs (2018)

Another movie where a kid with a drawn-on mustache falls in love with a kooky blonde? Jesus, man, see a shrink.

This movie came out just three years ago and yet I barely remember anything about it, other than that it was still mostly a good time. Animation does have a freeing effect on Wes Anderson. In some ways, it even feels like his true form. He can just stick characters exactly where he wants them for the sake of his picture-book compositions without having to worry about constraining the actors and making their performances seem awkward or stilted.

In that sense, Isle Of Dogs was fun, it looked cool, and it had lots of dog jokes, which is something you can get away within a movie called “Isle Of Dogs.” Still, it felt more like a bloated short than a feature in its own right. I’m not sure if that’s a failing on Wes Anderson’s part or on the film business as a whole, for their fairly rigid notions of what constitutes a feature. Isle of Dogs clocked in at 90 minutes, when the content only justified about 70.

And that would’ve been great! The world could use more 70-minute features.

6. The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004)

Life Aquatic is arguably the hardest film on this list to fit into a ranking. In one sense, it feels like Anderson taking big swings, making admirably bold narrative choices, even if they don’t always work out. It’s also the only Wes Anderson movie that, on some level, I plain don’t get. Even with The Darjeeling Limited, I think I have a sense of what he was trying to accomplish.

I have some very basic questions about Life Aquatic. When is it even supposed to be set? The film tells the story of Steve Zissou, clearly inspired by Jacques Cousteau (the red cap, the “Zissou Society”) but also with Zissou intended as the down-on-his-luck Salieri to a more famous Cousteau-type played by Jeff Goldblum. Clearly, the sets and tech and costumes are all 1970s-inspired, but Zissou is also a deliberate anachronism. He’s exactly the kind of character who would have out-of-date clothes and equipment. Does that mean The Life Aquatic is set in the eighties? The 90s? In 2004, when it came out? Does it matter?

There’s also the stop-motion animated animals. In an otherwise realistic-ish, live-action film about dueling sea explorers, the sea creatures themselves are almost purposefully unrealistic. The animated “sugar crabs,” the “crayon ponyfish,” “electric jellyfish,” and Zissou’s Ahab-esque obsession, the “Jaguar Shark,” they all feel a bit like Jim Henson-esque psychedelia. Which is… fine? Except the rest of the movie mostly isn’t that. And Wes Anderson doesn’t really seem like a “drug guy.” Meanwhile, there are real orcas and more real-looking dolphins (that the dolphins aren’t very smart or useful is one of Life Aquatic‘s better running jokes).

Anderson also seems to have just let the actors do whatever silly accent they wanted, from Owen Wilson’s antebellum southerner (supposedly a modern man from Kentucky) to Willem Dafoe’s German to Cate Blanchett’s Brit Girl Friday. Seu Jorge plays an ever-present intern who sings David Bowie songs in Portuguese, a character who seems to exist solely for vibes. The Life Aquatic combines expensive, incredibly complex and refined production design with a story that feels like a group of excitable high schoolers are making it up as they go along.

I enjoy the mushroom-trip qualities of Life Aquatic, its exuberant surrealism, its deadpan jokes — but every time it tries to do scenes with life-and-death stakes it falls flat. Are we even watching the film’s objective reality or is this all filtered through Steve Zissou’s addled mind somehow? Wes Anderson should probably just take the Dogme 95 pledge and never film another gunfight or murder.

5. Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

The end credits of Grand Budapest Hotel read “inspired by the writings of Stefan Zweig.”

This week I finally started reading Zweig’s The World Of Yesterday: Memoirs Of A European. Written by a Jewish writer from Vienna who was born in the Belle Epoque and lived to see two world wars, it consists of romantic musings by an author who grew up in a place that no longer exists. Zweig, who killed himself in 1942, is so eloquent but open-eyed about his childhood, both nostalgic for and critical of a time period that seems so many generations past but that he actually lived through. It’s romantic and heartbreaking, and reading it made me feel like I finally understood exactly what Anderson was going for in Grand Budapest Hotel. It also brings into focus all the ways the movie falls short.

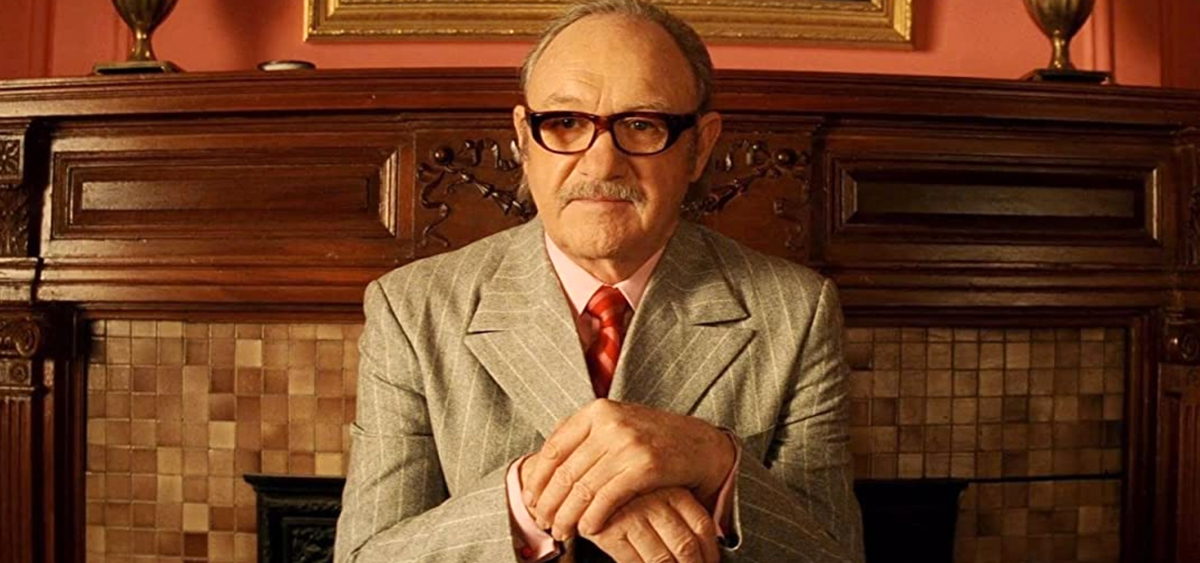

Visually, it’s certainly one of Anderson’s best. It’d be hard to think of a more ideal setting for his particular talents than an Alpine spa in inter-war Europe. The story is framed around a present-day monument to a European writer, presumably a fictionalized Zweig. Tom Wilkinson plays this author at one point, narrating one frame of the story, with Jude Law as the author’s younger incarnation, pressing aging hotelier “Mr. Moustafa” (F. Murray Abraham) for his story in the post-war years in another frame. This frame in turn leads into a flashback to Mr. Moustafa as a young Lobby Boy named Zero (played by Tony Revelori) being mentored by the hotel’s squirrely concierge, M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes). This is back in the 1930s, when the bulk of the story takes place.

The F. Murray Abraham frame is by far the strongest. Abraham has the perfect face and voice for conveying that sense of intense sadness and loss, while filtering it through a mask of elaborate Victorian manners and restraint. The abrupt way his tale of M. Gustave ends — “What happened to him? Well, they shot him, of course” — hits like an emotional gut-punch (Anderson is generally very good at endings, truly a rare skill).

Yet GBH is also, unfortunately, glib and cutesy. M. Gustave actually seems a lot like Mr. Norris, a vain and effeminate huckster in 1930s Berlin created by another inter-war writer, Christopher Isherwood, who likewise lived through those decadent years that gave us the Nazis. Like Norris, Gustave is a courtly bullshitter, and there are times Anderson gets so lost in Gustave’s flowery nonsense that it drags down the film. There’s a lengthy subplot about Gustave inheriting a piece of famous artwork from a widow played by Tilda Swinton, leading to a wacky prison break and eventually a droll shoot-out, in a film that should be neither wacky nor droll. Farcical, maybe, but not zany.

Meanwhile, Zero has a fake mustache he draws on every morning and his girlfriend (Saoirse Ronan) has a birthmark on her cheek shaped like Mexico. Probably the two most infuriatingly cute elements of any Wes Anderson film. Couldn’t we have gotten more of Jude Law and F. Murray Abraham? Of Edward Norton’s reluctant fascist? You can occasionally see what Grand Budapest Hotel is going for, and it’s wonderful, but when it misses it’s excruciating.

4. Bottle Rocket (1996)

I had this ranked much lower last time I wrote these rankings, but I rewatched it again and… I don’t want to say I was wrong about it before but I think I was unfair in some ways? Maybe I was overly influenced by the number of people I hear say this is their favorite Wes Anderson movie. Which to me is mostly just another way of saying “I liked him before he was cool.”

That aspect of it aside, Bottle Rocket is, essentially, Wes Anderson’s origin story in the business. It all started with a short film written by Anderson and Owen Wilson:

Mr. Wilson and Mr. Anderson, who had met in a playwriting class at the University of Texas at Dallas, were sharing an apartment when they decided to make a movie. Their original plan was to shoot a 16-millimeter black-and-white feature. Thirteen minutes of film and $10,000 later, they were broke. So they decided to call what they had of “Bottle Rocket” a short and submit it to the Sundance Film Festival, where it was shown in 1993. –New York Times, February 4, 1996

After that, nothing happened for a while, until they eventually found a champion in Peter Bogdanovich’s ex-wife and former producing partner, Polly Platt.

The screenwriter L. M. Kit Carson, a friend of the Wilson family, had sent the “Bottle Rocket” script and a video of the short to the producer Barbara Boyle, who in turn sent the material to Ms. Platt. Ms. Platt, a successful producer and production designer, was then the executive vice president of Gracie Films, Mr. Brooks’s production company. Under an arrangement with Columbia Pictures, the studio had agreed to finance a low-budget feature of Mr. Brooks’s choice. When Ms. Platt found “Bottle Rocket,” she knew she had the movie.

“Mr. Brooks,” of course, was Oscar-winner, Simpsons executive producer, etc James L. Brooks. This is one of those stories that seems to illustrate why any good movie ever getting made at all is damn near a miracle. Wes Anderson, now recognized as precocious and polished an artist that ever lived, managed to scrape together $10 grand to make a short, managed to get it into Sundance, and even after all of that, he was lucky that he just happened to know someone who knew a producer who knew another producer who worked for James L. Brooks. Who, luckily, loved the short and agreed to expand it into a feature. A feature that ultimately grossed just over half a million dollars in 49 theaters, having been seen by dozens of people. Don’t kid yourself, this making movies shit is hard.

Aaaanyway, the movie. Bottle Rocket was Anderson’s first feature and lowest budget, and because of these logistical challenges, it’s clear that he didn’t have the time and money that he would have on later films to meticulously plan every composition. For other filmmakers, this might be a bad thing, but with Wes Anderson, it might be a benefit. He didn’t have the time or money to be so fussy. Characters seemed to have more freedom to just act naturally, rather than try to fit themselves into some elaborately choreographed camera move.

The feature version cost just $5 million to make and James Caan, who had a small part, was the most famous actor in it. Caan plays “Mr. Henry,” an older eccentric, idolized by Wilson’s Dignan, who Caan’s character later double-crosses (they originally wanted a director for the role, Tarantino or Oliver Stone or Peter Bogdanovich). If Bottle Rocket had been made after Wes Anderson was already famous you can imagine them spending at least half that $5 million just on the sets for James Caan’s character alone. Instead, Anderson had to convey Mr. Henry’s faux worldiness with a shell necklace, one stuffed ocelot, and a sort of modernist-looking couch. Mr. Henry ends up seeming like a character out of a Jared Hess (Napoleon Dynamite) movie, or early Danny McBride. That makes Bottle Rocket feel a little like Trader Joe’s Wes Anderson, made back when he was an artiste but still living in Texas, with caviar tastes on a burrito budget.

The rest of the plot is about Dignan trying to convince Luke Wilson’s Anthony, whom he “breaks out” of a mental hospital (Anthony was always free to go) in the first scene, to do harebrained heists with him. As always with Wes Anderson, there is a decided lack of stakes in the heist scenes. In real life, it would’ve probably ended with Dignan getting shot 37 times by Texas cops.

Mostly, Bottle Rocket feels like what it is: a promising first effort by a future auteur more than a masterpiece in its own right. It’s strong on memorable images and enjoyable dialogue, but you also get the sense Anderson and the Wilson’s spent a lot more time thinking about what would be cool for these characters to do than who they were.

I hear Royal Tenenbaum asking “Characters? What characters? All I saw were a bunch of little kids running around in costumes,” so many times while watching Wes Anderson movies that I wonder whether the line actually grew out of Anderson’s own self-criticism.

3. Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009)

It seems to me that there are two types of Wes Anderson movies, Grand Statement Wes Anderson and Playtime Wes Anderson. He tends to alternate between the two. Fantastic Mr. Fox, coming just after The Darjeeling Limited definitely feels like Playtime Wes Anderson, an attempt to do something light after something heavy. And it works. Wes Anderson’s style might not be the ideal fit for Indian boys drowning or the rise of Fascism, but it does seem very well-suited for a story that asks “What if there was a rascally fox?”

There’s also an obvious advantage to Wes Anderson doing animation: he doesn’t have to worry about actors struggling to seem natural while moving about in highly choreographed ways for very specific compositions. In that way, Fantastic Mr. Fox combines the breezy casualness of Bottle Rocket with the elaborate compositions and ornate production design of The Life Aquatic. There isn’t much about Fantastic Mr. Fox that has necessarily stuck with me, thematically, but it sticks out in my mind as a fun time at the movies, and that’s enough.

2. The French Dispatch (2021)

In my mind, this is my favorite Wes Anderson movie. The only reason I don’t have it higher is that I just saw it, and without any distance from it it’s hard to know what how much of it will stay with me five or six years from now.

But right now, Bill Murray’s character’s exhortation to his staff at the French Dispatch, “Whatever you write, just try to make it seem like you did it on purpose” is echoing around my head the way Royal Tenenbaum’s line about little kids in costumes has been for the last 20 years. It’s another perfect Wes Anderson line that doubles as an apt criticism of Wes Anderson movies. I spent half of Life Aquatic wondering “did he mean to do that?”

Told in the form of newspaper sections separated by title cards, The French Dispatch is a kind anthology, a collection of shorter stories a la The Ballad Of Buster Scruggs. Like Buster Scruggs, the French Dispatch‘s episodic structure feels more revealing of its creator than a single storyline would’ve been, bringing all of their pet themes into sharper focus. It’s genuinely horny where some Wes Anderson movies are merely cute, vulnerable where others deflect, heartfelt where others are dry, and above all, it’s a map of Wes Anderson’s three primary obsessions: trying to fuck, trying to please a withholding father figure, and trying to please an authoritarian mother figure (who you also want to fuck).

Because it’s told in the form of a newspaper with a team of overly-enthusiastic writers, it’s also something of a love letter to overwrought prose. Wes Anderson is never funnier than when he’s satirizing overwrought prose.

1. Rushmore (1998)

1. Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

It’s always tough for me to choose between Rushmore and Royal Tenenbaums (both co-written with Owen Wilson). They represent the yin-yang of Wes Anderson obsessions. Rushmore is about a precocious, artistic youth. Royal Tenenbaums is about precocious, artistic youths all grown up. Rushmore is about a protagonist trying to screw his teacher. Royal Tenenbaums is about a withholding father figure. Rushmore has two of Wes Anderson’s best characters, Max Fischer and Herman Blume. Royal Tenenbaums has the other two, Royal Tenenbaum and Eli Cash.

Tonally, Rushmore is Wes Anderson’s best movie. It has an anarchic spirit that some of the others lack. Max Fischer is such a perfect shithead that he might be the world’s only punk rock Little Lord Fauntleroy. It has some of Andersonia’s most memorable images, like Bill Murray ascending a diving board with a scotch and a cigarette, and Max Fischer’s towheaded protege (remember what I said about Wes Anderson loving manservants?) hocking a looch on the hood of Herman Blume’s car. The exchange “These are OR scrubs, Max.” “Oh, are they?” might be the best dumb joke in any Anderson movie.

Then again, Royal Tenenbaums has Richie Tenenbaum’s tennis meltdown. It has Royal Tenenbaum shitting on his daughter’s play, and it has Eli Cash the hack novelist, easily the best Wilson-brother character in the Anderson canon.

The phrases “what my book presupposes is, maybe he didn’t?” and “Characters? What characters?” are basically seared into my brain for all eternity.

Certainly, both have their flaws. Royal Tenenbaums is stilted at times, and I probably could’ve done without the Dalmatian mice. It has characters your most obnoxious friend has probably dressed as for Halloween at least once. Rushmore is gimmicky at times, and the Scottish bully feels like he escaped from a different, worse 90s comedy. Tenenbaums drags more in the middle, but crushes harder in the ending.

I go back and forth, but as of today, I’m calling this fight a draw.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.