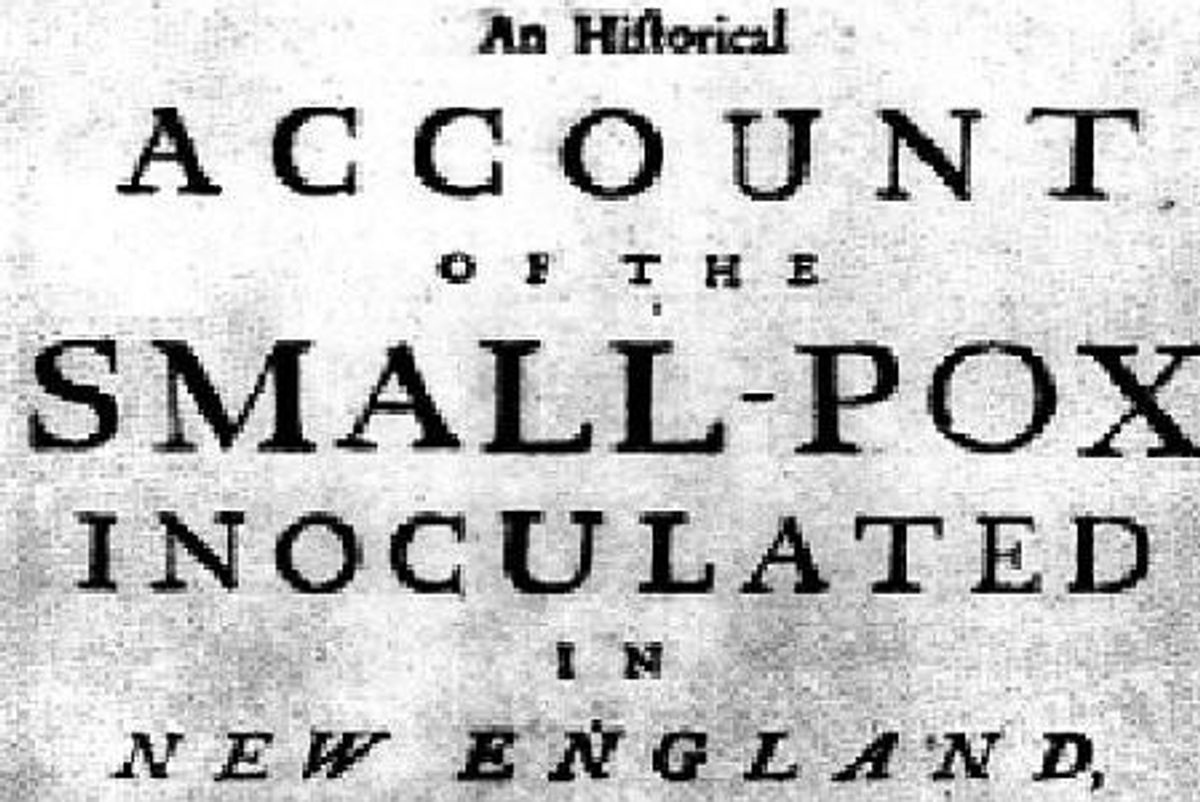

The early colonists of Boston were terrified—and nearly wiped out—by a rapidly spreading virus. As our modern society panics over incoming COVID-19 variants, I’m sure you can imagine the climate.

But instead of being taken by the deadly disease, Boston took part in a bold new experiment. As a result, smallpox was stopped in its tracks.

And it was thanks to the brilliant idea of an enslaved man, who really should be a household name for his contribution, one that remains a foundational principle in modern medicine.

Though an ancient affliction (as in, even the Egyptians knew about it), smallpox didn’t appear in the Western Hemisphere until 1507. But when it did, it killed an estimated 2 million among the native population alone.

Smallpox incited fever, fatigue, a nightmare-ish rash and worst of all, it was extremely contagious. The once-prosperous town of Boston had residents fleeing to avoid possible exposure.

But fate was changed in 1721, when a man named Onesimus shared how he once had smallpox. And that he overcame it.

Onesimus was a slave to Puritan minister Cotton Mather (major player in the Salem witch trials, swell guy), and was given his name from another enslaved man in the Bible whose name meant “useful.” Mather also referred to Onesimus as “wicked,” but something tells me Mather liked to dish out that descriptor a lot. And moreover, Onesimus proved to be indeed quite useful.

Onesimus told Mather the story of how he, too, contracted smallpox in Africa but “had undergone an operation, which had given him something of the smallpox and would forever preserve him from it…and whoever had the courage to use it was forever free of the fear of contagion.”

That operation would later be widely known as variolation, where a healthy person could make a small cut in their skin, then insert infectious material (in this case, pus from smallpox blisters) into the cut. You’re welcome for the visual.

Not being entirely trusting—shocker—Mather decided to research further. Lo and behold, this method had not only been used in Africa, but China and Turkey as well.

Wisdom did not beat racism so easily. Even Mather was accused of “Negroish thinking” while trying to promote the idea. Not to mention that, ironically, the very religion Mather idolized proved to be an obstacle, as other preachers claimed the practice to be “against God’s will.”

That tune changed after more than 14% of Boston’s population was decimated, and one physician showed his support. Zabdiel Boylston inoculated his son, and the slaves in his possession, and the results were impossible to ignore: of the 24 people inoculated, only six died.

Without Onesimus introducing this form of disease prevention, we very likely might still be facing smallpox today … if we survived, that is. The success of variolation planted the seed for new hope, and not much later, a vaccine based on cowpox would be developed.

Not much is known about what happened to Onesimus, other than partially purchasing his freedom from Mather. But we owe him a debt of recognition. This is a valuable story not only for the power of science, but for the amazing insight to be gained by respecting other cultures.

for

ussin btch WTF IS GOOD

#Bussin 2.11.22#DoWeHaveAProblem OUT NOW

#Bussin

ussin