The San Francisco World Spirits Competition is like the Oscars of alcohol. And like the Oscars — or the Grammys or the Emmys or the Saturn Awards — there’s a lot that goes on behind the scenes of this massive blind alcohol tasting that your average person watching it on television or seeing it from the outside couldn’t possibly know. Today, I hope to change that.

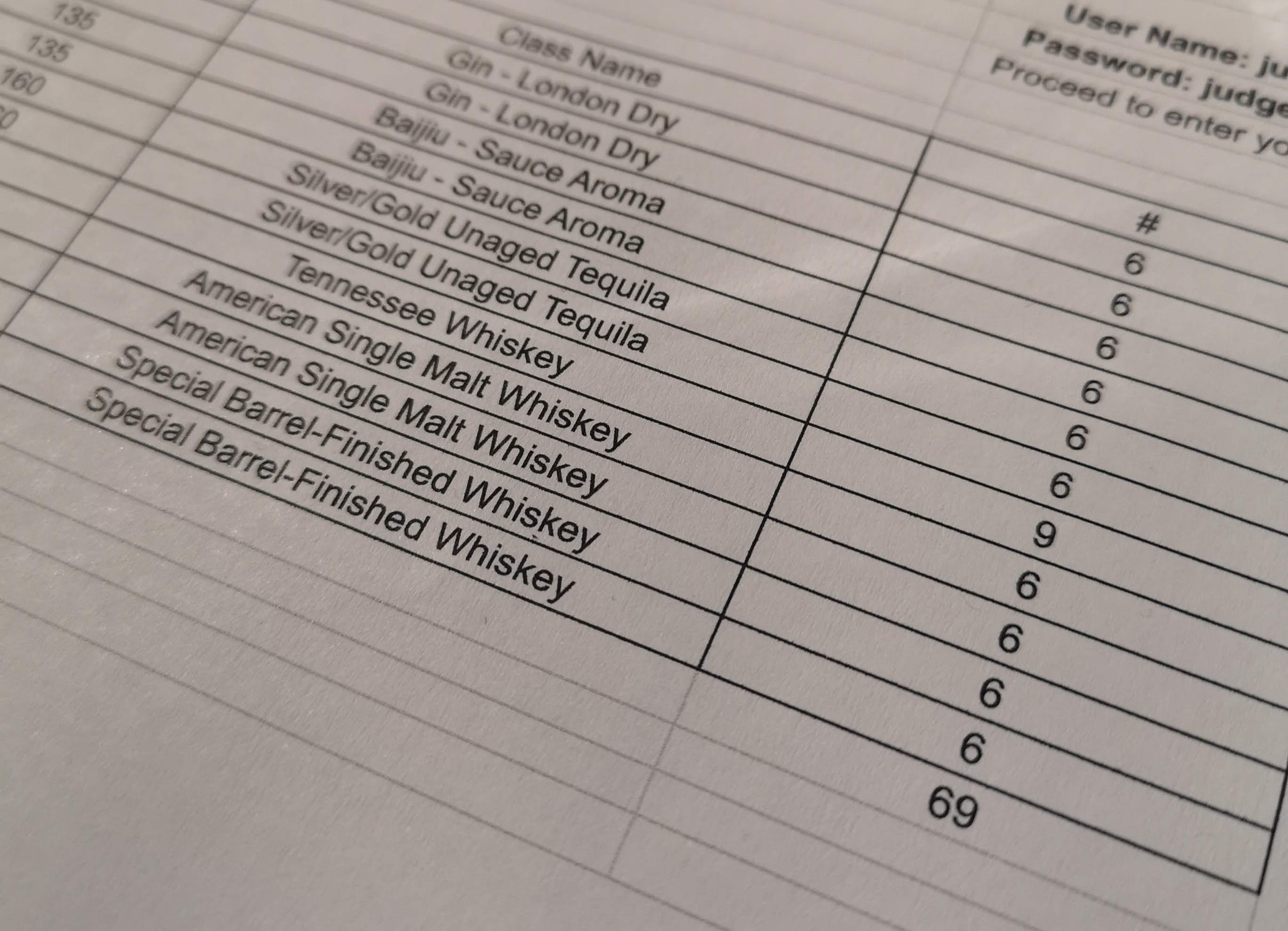

This year, I was lucky enough to judge four days of the sprawling SFWSC. In that time, I tasted 312 drams of alcohol double-blind — through 52 panels of booze. Most panels had six to nine glasses, with one having only four and another having 11. The liquor tasted came from all over the world, from calvados to baijiu to tequila to ready-to-drink cocktails to various whiskeys and pretty much everything in between. Hell, I even sat on a panel of fruit juice cocktail mixers.

All of this is to say that judging this event is for alcohol experts, not just “whiskey folks” or “rum pros” who focus on one thing. With that in mind, let’s get into the nitty-gritty.

Related: Double Gold Winners from the 2022 San Francisco World Spirits Competition on UPROXX

- All The Double Gold-Winning Straight Bourbons From This Year’s San Francisco World Spirits Competition

- All The Double Gold-Winning Single Barrel Bourbons From This Year’s SF World Spirits Competition

- All The Double Gold-Winning Small Batch Bourbons From This Year’s San Francisco World Spirits Competition

- The Best Reposado Tequila: All The Double-Gold Winners From This Year’s SF World Spirits Competition

- Full List Of Tequila And Mezcal Finalists From The SF Spirits Competition, Just In Time For Cinco De Mayo

- All The Canadian Whiskies That Won Double Gold At The Biggest Spirits Competition On Earth

- All The Double-Gold Winning Blended Scotch Whisky From This Year’s SF Spirits Competition

PART I — The Competition

The San Francisco World Spirit Competition has been around for 22 years. It was founded by Anthony Dias Blue, a legend in the industry, though me saying that may not mean much to industry outsiders. He’s kind of like John Huston. If you’re a film nerd, you know how important he is to film history. If you’re not, he’s the bad guy from Chinatown.

Over those 22 years, the competition has become the highlight of the alcohol award season. A “double gold” from SFWSC means prestige and, more importantly to the brand, sales. It provides a level of spotlight that brands can trade on. They’ll put neck hangers on bottles or stickers on labels declaring they’ve won double gold at the SFWSC, which adds a certain amount of shelf appeal at your local big box or liquor store. (There are also the bronze, silver, and gold medals that offer alcohol brands a certain cachet, but most of them aren’t putting silver or bronze medal stickers on their bottle to help sales.)

PART II — How It Works

Not to keep comparing this to the Oscars, but like that award ceremony, every candidate is based on a company, distributor, bottler, or distiller entering their bottle in the competition. It’s not based on people going out and finding the best bottles. That said, the team at SFWSC will reach out to new and cool brands to see if they want to enter — so the pool ends up being a balance of who knows to go for the gold and who’s cool right now.

In the end, the entries come from people entering their brand(s) with a fee and supplying the correct number of bottles for tasting panels. From there, the bottles are warehoused and sorted in San Francisco. Each bottle is then used to pour samples for judges. In the end, the bottles have to be disposed of, per law.

PART III — Who Attends

Anthony Dias Blue created a system where he’d invite the best of the best from the alcohol industry to San Francisco to judge spirits and award them medals (or eliminate them, but more on that later). This includes people from the media (like me), distributors, bar owners, sales reps, investors, experts, liquor store owners, and authors. People who work making the booze are generally not invited. Though with barrel picks becoming commonplace in whiskey, that line does get blurred (even I’ve done a barrel pick at Buffalo Trace).

My particular class of judges included people from local wine distribution in San Francisco to leading sake experts to media reps for liquor stores to bar owners to cocktail book authors. It’s a pretty wide net of alcohol-focused people and a diverse crew with even more diverse palates. As mentioned earlier, no one is there to taste only one spirit.

PART IV — The Table

The tables are set up with three or four judges at each. They’re round and we’re all spread out so we can’t see each other’s notes or medal picks while tasting. A curator comes around with a server and clears and places the glasses between each panel. We have a spitter (obviously), palate cleaners (more on that later), and flat and sparkling water bottles.

This year there were tablets to enter our tasting notes, thoughts, and medals — making the job of the curator much easier. Lastly, before you sit down, you put on a white robe. This gives the whole place an air of officiality, not to mention ceremony.

PART V — The Process

As I mentioned in the lede, judges work through six to 10 panels per day. Each panel is six to eight pours, on average, with the numbers hitting between 60 and 70 pours total each day, ideally. Those panels cover every category, with clear spirits generally coming early and dark stuff generally coming at the end.

Judges then tabulate their tasting notes and medals individually at a table. The curator then comes to the table and checks all the medal “scores.” If all the judges have given a pour a gold medal, that’s an automatic “double gold.”

Here’s the rub: judges don’t always agree. There’s a rainbow where, say, three judges each give a different medal — bronze, silver, and gold. Then the bronze and gold judge tries to convince silver to either come up or go down.

Going deeper, we don’t just assign a “Gold” or “Silver” — it’s actually “gold minus,” “gold,” or “gold plus” (and the same with the other medals). If, say, I assigned a gold minus and the rest of the table had silver pluses or just silvers, that signals to the other judges that I’m happy to lower to a silver medal for that pour. Whereas if someone marks something “gold plus” and the rest of us are average silvers, then that judge needs to make their case because gold plus means they’re blown away and the silvers mean the other judges were not. And in that instance, we’ll all go back to our Glencairns to re-nose and re-taste as one judge makes their argument.

Sometimes it’s convincing and we come up. Sometimes it’s not and they come down in their medal.

If something is ranked “double gold,” the judges then have to decide whether that bottle is going to “sweeps,” which is where the “best in class” bottles are decided. Judges rate the pour — between 94 and 99/100 — and those bottles are sent to the big show/another blind tasting at the end where a new set of judges taste them again. One way to think of it is that the “double gold” medal is like an Oscar nomination and the “best in class” is actually taking home the trophy.

PART VI — The Palate Cleansers

I ate so much cheese every day.

Here’s a hard and fast rule from Fred Minnick: Tasting alcohol is putting it on your tongue, drinking it is swallowing it. No one is drinking the alcohol. We all spit.

Every judge has a plate of soft Muenster cheese, celery, and baguette. I’d say on average, most judges take a bite of something every couple of drams, or at least at the end of every panel. I’ve used celery a lot in the past in my own blind taste tests for UPROXX, it’s a great neutralizer for your palate. The servers who bring around and clear the glasses are also moving around the room and refilling everyone’s palate cleanser plates throughout the day.

PART VII — The Marathon

We started at 9 am every morning, broke for lunch around noon, and then finished up by 3 pm. On one of those days, I had just over 80 drams. This was out of the ordinary. On that day, I was with Steve Beal (the guy who invented Bulleit for Diageo, amongst a million other legendary things) and Nate Gana (the world’s leading whiskey investing expert) and, I can tell you, we were all spent by the end.

It’s not so much that your palate gets blown out — there are breaks between every flight and plenty of palate cleansers. In fact, I’d argue that your palate gets more attuned as the day goes on. It’s more that your brain no longer knows what to do with the alcohol you’re teasing your system with. This leads me to…

PART VIII — What It Does To Your Mind and Body

If you talk to the people who taste an incredible amount of spirits for work, most of them will tell you they can no longer get drunk on that spirit. Basically, when you’re tasting whiskey on your tongue, your body sends signals to your brain that alcohol is coming in. But then you spit it out and remain sober. After a while, your brain just assumes that it takes 20, 30, or 50 shots to actually get you drunk because you can taste that much without getting drunk physically. It’s wild. I’ve stopped drinking whiskey recreationally because I don’t even get a buzz anymore, and I can assure you (hearsay or not) that I’m not the only one in the industry with this “problem.”

But there comes a point where you’re 60-odd pours in and your brain starts rebelling. It’s just had enough, which would be true of any food or drink judging position. Then your body rebels too. It wants anything else. You have a little bit of sea legs when you get up to leave but you want to leave as fast as possible. Ironically, you end up running toward very big flavors in food and a strong beer, cocktails, or wine (anything that’s not a neat spirit pour) because, again, your taste/palate is still there, sharper than ever even, but your body is kind of tired of being teased.

PART IX — Recovery

Each late afternoon and evening is all about the food and drinks. That said, some judges have to go to work at their bars or liquor stores after a whole day of judging, so I’m not speaking for everyone here. Still, your palate needs a full reset. Sazeracs, crisp white wines, and old-school West Coast IPAs are all in order. So many oysters, funky charcuteries boards, and spicy ramen bowls are had — really anything to wake up and reset the senses but also nourish your head.

Then sleep. At some point, you just shut down and sleep until the alarm goes off and you’re back at the judging table.

PART X — It’s Really Not What You Think

View this post on Instagram

Let’s talk about the dreaded “E” on the medal list. Yes, some bottles are just straight-up eliminated. It’s rare but not super rare. So while it feels like judges are giving out double gold medals left and right, we really aren’t.

This is how my tables judged the spirits point by point:

- Is the actual spirit well made? Do they know what they’re doing?

- Next, does this deliver on what is promised? (Does the “Blueberry Gin” actually taste like blueberries?)

- Finally, how refined/good is it overall? Does it stand out from the other spirits in the same panel? Are there flaws in the blend that feel out of place? Is it an instant “wow”?

I can tell you from experience that the bottles that rise to the top are instantly identifiable as perfectly crafted. But they also stand out amongst the six to nine other glasses in front of the judges as having “something extra.”

Overall though, there’s way more “that was fine” than “wow, that’s amazing.” And the “wow, that’s amazing” is what gets double gold and sent to sweeps for “best in class.” This is especially true of the whiskey categories where there are so many options (over 1,000 this year). The vast majority of those didn’t get double gold, much less sent to sweeps for a chance at best in class.

That said, it was super clear when one, two, maybe three pours in a panel tasted better than the rest. Bad booze is bad. Average booze is average. The greats truly do grab your attention. Yes, subjective palates come into play, but that’s where the aforementioned “gold minus,” “gold,” and “gold plus” nuances in grading come in. If something really speaks to you, then it’s on you as a judge to make your case for that pour.

Final Thoughts:

312 pours of alcohol in four days is a lot… for anyone. As of this writing, I’ve only had 420 pours of individual whiskeys in the first four months of 2022. That being said, those 312 pours average out to six pours per judging panel, which isn’t that hardcore.

It took me about three days to really recover from this process. One, I shouldn’t have done it four days in a row. The pros do two days and have a break and then come back for a couple of days and so on. Luckily, I spent a long weekend in Napa Valley trying to get my body back in line with a lot of wine and food. I did try to drink a rye whiskey in Napa, but couldn’t get it down. My body was just too used to spitting all the spirits I tasted. It took about a week for my ability to actually swallow neat spirits to come back.

In the end, it was an experience that doesn’t really have a parallel in this job. It’s definitely illuminating in what you learn about booze — there’s a lot of hot trash out there that my work at UPROXX hadn’t really exposed me to, folks. In fact, I’d say there’s more trash than gems by far. And that’s sort of the point of these awards, finding those gems. It was my pleasure to track them down for you this year and I hope you find a few that work their way into your drinking rotation.

You can see all the medal winners from the 2022 San Francisco World Spirits Competition here.