The world premiere of Top Gun: Maverick was a typically lavish affair. But the biggest moment of the evening was reserved for the arrival of its leading man. Rather than arrive via limo, Tom Cruise entered the party in a helicopter, the kind of bombastic declaration of one’s presence that befits only the most famous and iconic of stars.

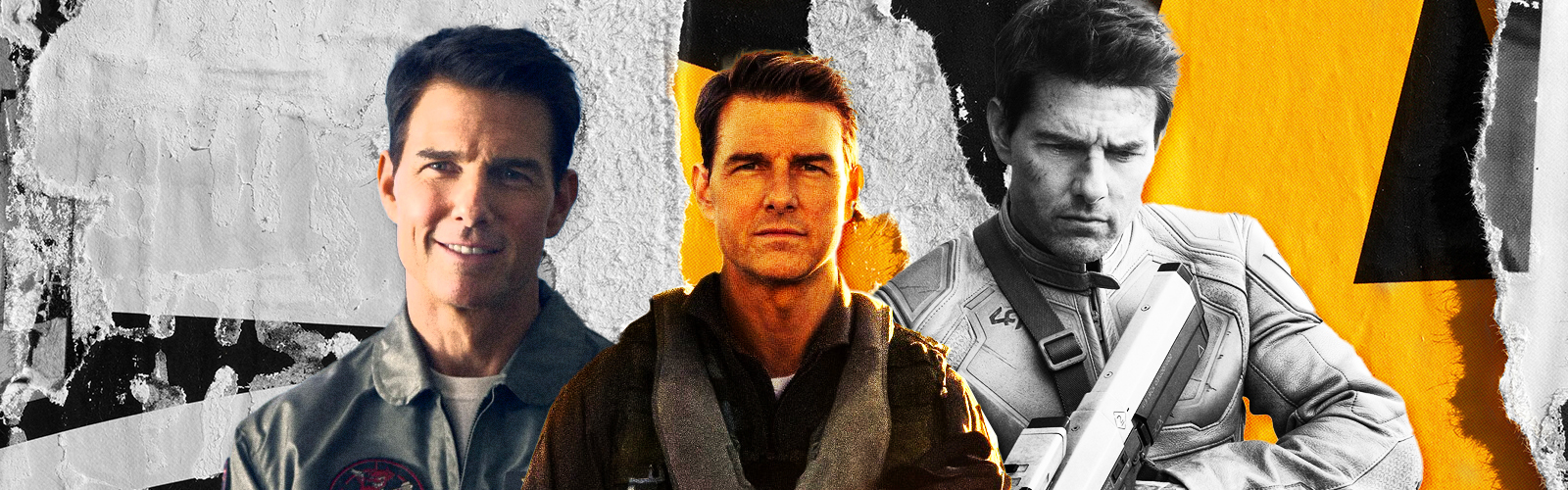

Top Gun: Maverick is an increasing rarity in the oversaturated market of Hollywood blockbusters: a practical stunts-driven star vehicle that, while a sequel to a notable IP, is defined almost entirely by its leading man. Actors don’t tend to get above-the-title credits with MCU movies or other such franchises but Cruise’s name is right there. Cruise’s films have grossed over $10.1 billion worldwide. He’s been Oscar-nominated three times and worked with the likes of Oliver Stone, Stanley Kubrick, and Michael Mann. At the age of 59, he is still headlining massively costly blockbusters, keeping critics and audiences on his side, and maintaining his A-List power. He’s almost invincible, the last movie star standing in a changing Hollywood.

True megastars get to do things that nobody else can. They earn more money, they demand major rewrites, and they can bend even the most inflexible of industry stalwarts to their will. That level of power demands consistency and results. And while Cruise has bounced between more serious dramas and blockbusters for the majority of his career, there is also a specific formula that he often follows, as laid out by Roger Ebert in his review of 1990’s Days of Thunder.

This checklist of nine requirements reveals the template that has strengthened Cruise’s stardom in the years since: stories of “rambunctious” scamps with undeniable talent who come up against unexpected obstacles, get the girl, learn from their mentor, and prove their mettle in the face of doom. While not every film he’s made fits into this structure, it’s remarkable how many of them do over the course of 35+ years. Cruise gets older but he’s retained that go-getter energy and thrall that fits so well into stories of heroes going up against the rest of the world. It’s not a formula he’s had to change all that much, even as fellow megastars find themselves struggling with new demands and their old ways losing popularity with audiences.

The jewel in the crown for Cruise remains the Mission: Impossible franchise. This is his domain, the platform from which he can be the unbeatable idol of blockbusters worldwide. What started out as a big-budget remake of a ‘60s TV show evolved into a singularly Cruise-ian endeavor. The first film quickly eschewed the tenets of the source material (much to the chagrin of some fans) to fully center Cruise in every way. New cast members and creatives would come and go across the franchise, but Cruise remained front and center. The Mission: Impossible franchise allowed Cruise to be the kind of movie star that simply doesn’t exist anymore. Always keen to perform his own stunts (the fish tank scene in the first film happened at his insistence, with no stunt man in his place), each movie brought progressively bigger and more dangerous set-pieces that allowed Cruise to be a real-life action man.

Stunts are dangerous, costly, and dependent on years of training and planning. There’s a reason that you don’t see any of the Marvel stars flinging themselves off of skyscrapers. Robert Pattinson doesn’t get to fly from rooftops with his Batsuit. Nowadays, stunt workers are more in-demand than ever for such work and the advancement of hyper-realistic CGI has helped to make such things safer than ever. Yet Cruise does it all himself. He jumps across buildings, shattering his ankle in the process. He does motorcycle chases without a helmet. He clings to the side of planes as they take off. He sat atop the tallest building in the world for a casual selfie. And this doesn’t even include the stunts he’s done in other movies. There are plots in these movies but, let’s be honest, people love the Mission: Impossible franchise because it’s evolved into a ceaseless spectacle of A-List stunt madness, with one of the most famous people on the planet doing the kind of things that, once again, you can only do if you’re mega-rich and powerful and no one wants to tell you no. There’s a realness to seeing an actual movie star literally skydive for our personal entertainment. Not since Jackie Chan have we had this kind of starry thrill.

It’s the Mission: Impossible franchise that has allowed Cruise to stay on top. He makes a lot of interesting non-franchise blockbusters such as Oblivion and Edge of Tomorrow, both of which are great and are a reminder of how star power can get such films made. Yet it’s hard to ignore the way that his biggest project has bolstered his career during some slippery periods. In the mid-2000s, Cruise’s image took a beating thanks to some questionable interviews, his louder-than-ever support for the Church of Scientology, and the parody-ready public romance that was his marriage to Katie Holmes. Cruise hadn’t been defined in Hollywood as an everyman for a long time but this era saw him become a joke, a “weirdo,” the kind of guy that his audiences felt put off by. To many, this might be an endgame moment. But Cruise found a way around it.

If you can’t be relatable or accept a shift toward playing regular old guys, then the next logical step is to be the opposite of that. What better way to solidify your place as an all-powerful and untouchable superstar of epic proportions than by doing the kinds of things in movies that nobody else can, will, or should? The last three Mission: Impossible films have helped Cruise in this effort, propelling him past those past controversies. It’s not that they aren’t there anymore, people are just distracted by the spectacle of what he’s doing on screen.

Cruise might be making physically dangerous movies but, despite his unique position (or maybe with its preservation in mind), he’s not exactly a creative risk-taker with his projects. This isn’t an actor who’s using his clout to get hubristic vanity projects made. There’s no Hudson Hawk or Heaven’s Gate in his filmography. The past 15 years or so of work have seen Cruise almost entirely eschew darker roles and the kinds of auteur-driven narratives he once felt so comfortable in. There’s nothing as nervy as Magnolia or even Interview with the Vampire in his 2010s filmography, although one could make the case that his turn as a faded rockstar in the musical Rock of Ages comes somewhat close. He doesn’t remold himself to fit new projects anymore. Rather, the movies must bend to his brand, and sometimes that leads to a clunky failure like The Mummy, a remake of a quiet horror classic that became a set-piece laden tentpole piece to match Cruise’s stunt-focused heroism in the Mission Impossible series.

Cruise’s preference to avoid those kinds of risks does feel like a loss in many ways. He could be a nervy actor, one with a ferocity and mischief that made him as good a fit for Born in the Fourth of July as it did for Jerry Maguire. He, the classic good guy, made for an impeccable villain too, as seen in Michael Mann’s Collateral, a noir-inspired drama that allowed him to use that old-school handsome demeanor for something far more chilling. Brad Pitt still works with filmmakers of ambition and curiosity. Will Smith just won an Oscar. It’s hard to imagine Cruise taking similar paths in the future.

He seems to have given up on being that kind of actor. Indeed, he’s less an actor now than a star, and that seems to be how he – and maybe the public – prefer it. We’ve been led to believe he is something more than mortal, defying perceived physical and mental limitations and the cruelty of time for a long time while continuing to be the dictionary definition of a movie star while others fade or flee from the weight of that role. For Cruise, the question may well be, why try to be anything less than that image if you don’t have to?