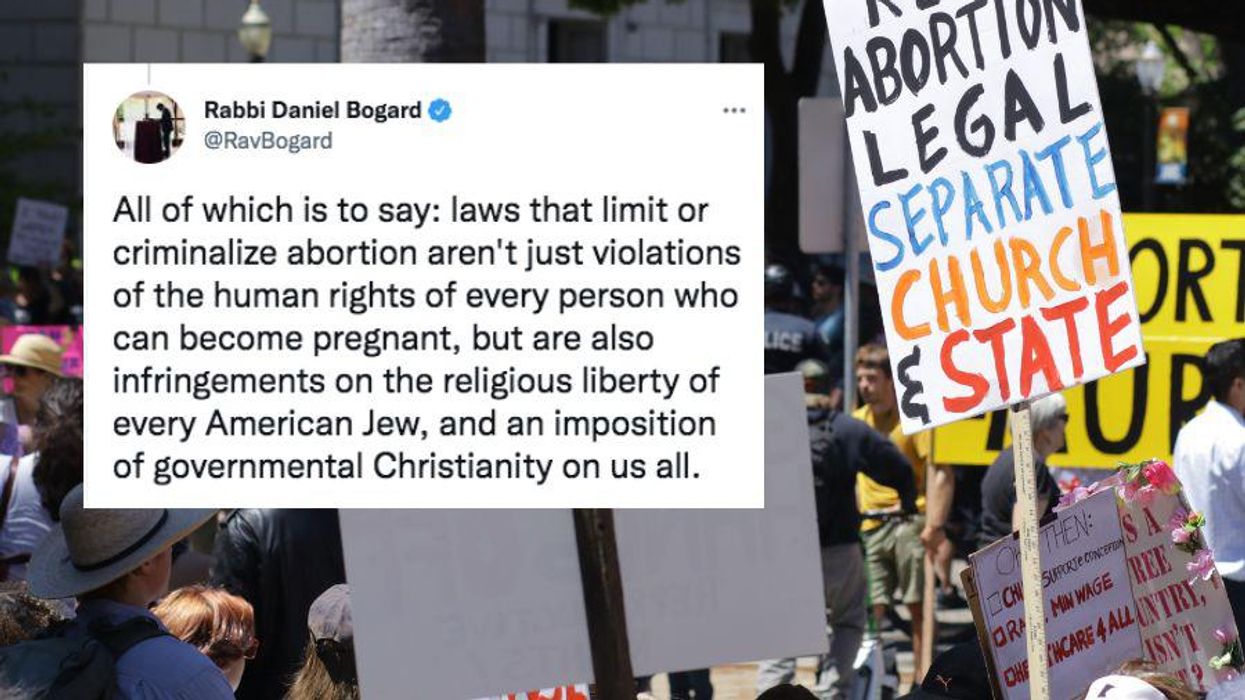

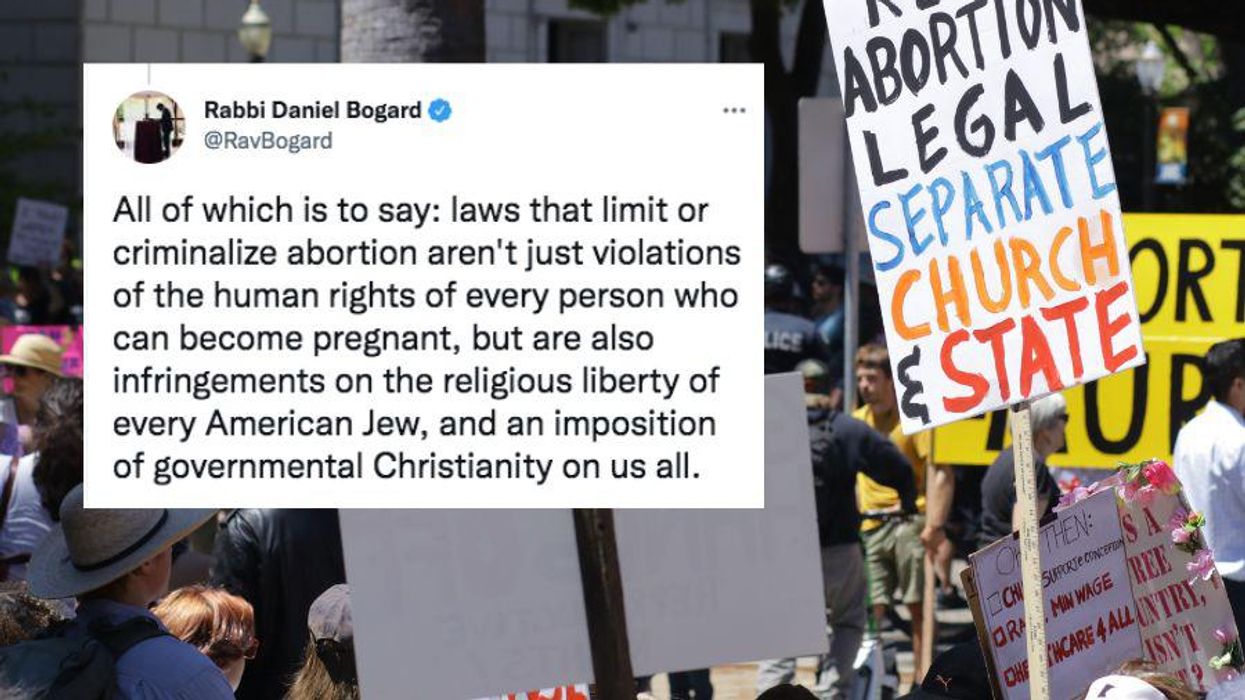

Debate over legal access to abortion has long been a part of social and political discourse, but increasing state-level restrictions and a leaked Supreme Court draft opinion that threatens to overturn five decades of legal precedent have propelled abortion directly into the spotlight once again.

While we’re accustomed to seeing religious arguments against abortion from Christian organizations, a synagogue in Florida is flipping the script, making the argument that banning abortion actually violates Jewish religious liberty.

In a lawsuit against the Florida government, Congregation L’Dor Va-Dor of Boynton Beach says that the state’s pending abortion law, which prohibits abortion after 15 weeks with few exceptions, violates the Jewish teaching that abortion “is required if necessary to protect the health, mental or physical well-being of the woman.” Citing the constitutional right to freedom of religion, the lawsuit states that the act “prohibits Jewish women from practicing their faith free of government intrusion and this violates their privacy rights and religious freedom.”

Wow.

The Florida 15-week abortion ban only grants exceptions if the mother’s life is at risk, if she is at risk of “irreversible physical impairment” or if the fetus is found to have a fatal abnormality. There are no exceptions for rape, incest or human trafficking.

If Jewish law stipulates that access to abortion is required not only for a woman’s physical well-being but also her mental well-being, then laws that criminalize such access are violating religious freedom, Congregation L’Dor Va-Dor contends.

Advocating for abortion access is not the religious argument we usually hear, but it is on equal footing with religious arguments against it. (It’s worth pointing out that Governor Ron DeSantis signed the Florida abortion act into law not at his office, but rather at a church.)

The synagogue’s lawsuit raises the question of which religion takes precedence when it comes to legislation. It also highlights the difference between “This is against my religion, therefore no one can do it” and “This is part of my religious tradition, therefore I legally have a right to access it.” The former really has no place in U.S. law, as it violates the traditional separation of church and state, and the latter is a prime example of the purpose of the First Amendment right to freedom of religion.

Part of what makes legislating abortion so messy is that the questions at the heart of the debate are actually largely religious in nature. What is the true nature of human life and when does life begin? At what point is a zygote, an embryo, a fetus considered a full human being with the same rights as the rest of us? What is the relationship between a human (or potential human) in the womb and the person whose body is building it? What responsibilities does the person who is building it have toward that life, and what responsibility does society and/or the government have in holding the human accountable for those responsibilities?

These are all legitimate questions that don’t have easy, straightforward answers, no matter how simplistic and undernuanced people try to make them. They may be simple questions for some people to answer individually, but collectively? No. We all make those determinations based on different criteria, different beliefs, different values and different understandings of the nature of life. There is no way for “we the people” as a whole to answer those questions definitively.

And the implications of those questions extend far beyond the abortion debate. The Cleveland Clinic states that one-third to a half of pregnancies end in miscarriage before a person even knows they’re pregnant. For those who believe that life begins at conception or fertilization, should every death in the womb be considered a tragedy? Should we mourn the loss of lives we carried that we never even knew existed?

There are the slippery slopes that stem from those questions as well. Some religious people may see a miscarriage as God’s will, but what if it was caused by something a woman did? What if a miscarriage occurred because of an action taken of her own free will? Is she culpable for that loss using the same logic we use to criminalize abortion? At what point do we start policing women’s behaviors—what she eats or drinks, what medications she takes, whether she’s around smokers, and so on—at all times in order to protect a life she may potentially be carrying? We’re already seeing women being jailed for miscarriages. How far will we go with it?

What about things like child support payments and government benefits? Why we do not expect child support to be paid from the moment a pregnancy is detected? Why do we not give Social Security numbers to Americans in the womb? Why can we not claim a child on our taxes until they are born? If there is genuinely no difference between a life being grown inside a uterus at 12 or 15 or 20 weeks and a life outside a uterus, why does the law treat them differently?

How do we begin to answer these questions when the heart of them always circles back to individual beliefs?

The synagogue’s religious freedom argument is compelling for sure, but the bottom line is we shouldn’t be legislating on something based on religious beliefs in the first place. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…” That’s literally the opening line of the First Amendment of the Constitution. Banning abortion is, in effect, establishing a particular religious belief as law and prohibiting the free exercise of religion for an entire group of people.

At a basic level, abortion is 1) a medical event that entails far too many individual factors that are not the business of the government to judge, and 2) a choice that is determined to be valid or invalid, right or wrong, based largely on individual religious beliefs. Both of those realities are reason enough for legislators, who are neither medical professionals nor religious leaders, to stay out of people’s uteruses and leave these incredibly personal medical and religious decisions to the individual.