Marlon Brando made one of the biggest Hollywood comebacks in 1972 after playing the iconic role of Vito Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather.” The venerable actor’s career had been on a decline for years after a series of flops and increasingly unruly behavior on set.

Brando was a shoo-in for Best Actor at the 1973 Academy Awards, so the actor decided to use the opportunity to make an important point about Native American representation in Hollywood.

Instead of attending the ceremony, he sent Sacheen Littlefeather, a Yaqui and Apache actress and activist dressed in traditional clothing, to talk about the injustices faced by Native Americans.

She explained that Brando “very regretfully cannot accept this generous award, the reasons for this being…are the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry and on television in movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee.”

The unexpected surprise was greeted with a mixture of applause and boos from the audience and would be the butt of jokes told by presenters including Clint Eastwood. Littlefeather later said that John Wayne attempted to assault her backstage.

“A lot of people were making money off of that racism of the Hollywood Indian,” Littlefeather told KQED. “Of course, they’re going to boo. They don’t want their evening interrupted.”

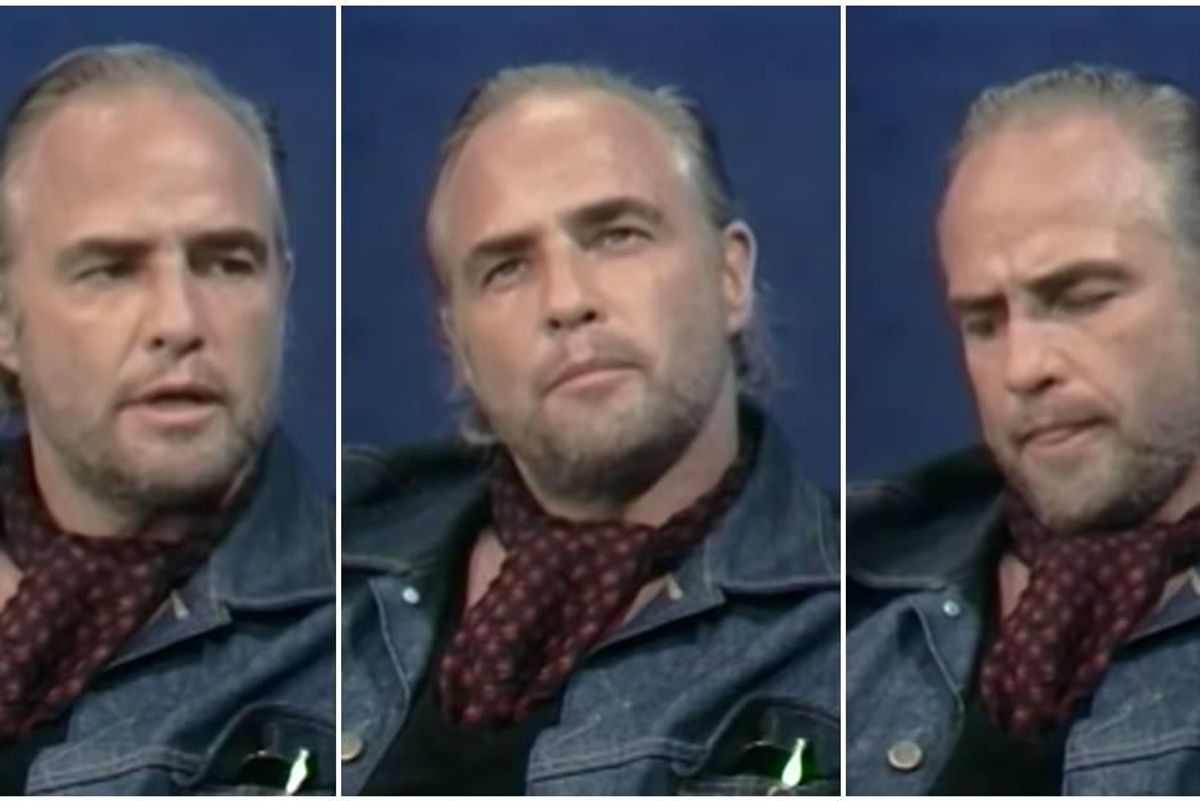

Three months later, Brando explained his reasoning in an interview with late-night host Dick Cavett where he also discussed how all people of color are misrepresented in Hollywood. The interview was historic because Brando was known for avoiding the media.

“I felt there was an opportunity,” Brando told Cavett about the awards ceremony. “Since the American Indian hasn’t been able to have his voice heard anywhere in the history of the United States, I thought it was a marvelous opportunity to voice his opinion to 85 million people. I felt that he had a right to, in view of what Hollywood has done to him.”

Brando’s eyes were opened after reading John Collier’s novel “Indians of The Americas.”

“After reading the book I realized, I knew nothing about the American Indian, and everything that we are taught about the American Indian is wrong,” Brando said. “It’s inaccurate. Our school books are hopelessly lacking, criminally lacking, in revealing what our relationship was with the Indian.”

“When we hear, as we’ve heard throughout all our lives, no matter how old we are, that we are a country that stands for freedom, for rightness, for justice for everyone, it simply doesn’t apply to those who are not white,” Brando said. “It just simply doesn’t apply, and we were simply the most rapacious, aggressive, destructive, torturing, monstrous people who swept from one coast to the other murdering and causing mayhem among the Indians.”

Brando understood that the boos from his contemporaries were the sounds of powerful people who couldn’t stand having their industry and reality challenged. It was the sound of pure denial.

But Brando was unapologetic about bursting the audience’s collective bubble.

“They were booing because they thought, ‘This moment is sacrosanct, and you’re ruining our fantasy with this intrusion of reality. I suppose it was unkind of me to do that, but there was a larger issue, and it’s an issue that no one in the motion picture industry has ever addressed themselves to, unless forced to,” Brando said.

“The Godfather” star then expanded his thoughts on representation to include all people of color.

“I don’t think people realize what the motion picture industry has done to the American Indian, and a matter of fact, all ethnic groups. All minorities. All non-whites,” he said. “So when someone makes a protest of some kind and says, ‘No, please don’t present the Chinese this way.’ … On this network, you can see silly renditions of human behavior. The leering Filipino houseboy, the wily Japanese or the kook or the gook. The idiot Black man, the stupid Indian. It goes on and on and on, and people don’t realize how deeply these people are injured by seeing themselves represented—not the adults, who are already inured to that kind of pain and pressure, but the children. Indian children, seeing Indians represented as savage, ugly, vicious, treacherous, drunken—they grow up only with a negative image of themselves, and it lasts a lifetime.”

Hollywood is still far from ideal when it comes to being truly representative of America at large. But it is miles ahead of where it was in 1973 when the film industry, including some of its biggest stars, was outwardly hostile toward the idea of representation.

In 1973, Marlon Brando was at the height of his power which most would have relished after a series of setbacks. But instead of taking the opportunity to bask in the spotlight, he spent a large portion of his star power capital to give voice to the people Hollywood had dehumanized for seven decades.