Pigskin has already proven to be extremely useful for treating wounds, due to being genetically similar human skin. But can it cure blindness? The science seems to lead toward yes.

A new study, published in Nature Biotechnology, revealed that 14 out of 14 blind patients significantly restored their eyesight—with a few even achieving perfect 20/20 vision—after receiving bioengineered implants made of collagen, a protein found in human skin, and, you guessed it … pigskin.

Each of the patients, all in Iran and India, suffered from a progressive condition called keratoconus, where the cornea (the transparent layer that covers the pupil and iris) thins and gradually bulges outward into a cone shape.

Corneal damage is one of the leading causes of blindness globally, and though it is currently treatable through transplants, there is a low amount of human donor corneas available, especially to those with low to middle income.

Being a food byproduct, pigskin is not only accessible, but a much more cost-effective transplant material. That’s what makes this study and its findings so potentially groundbreaking.

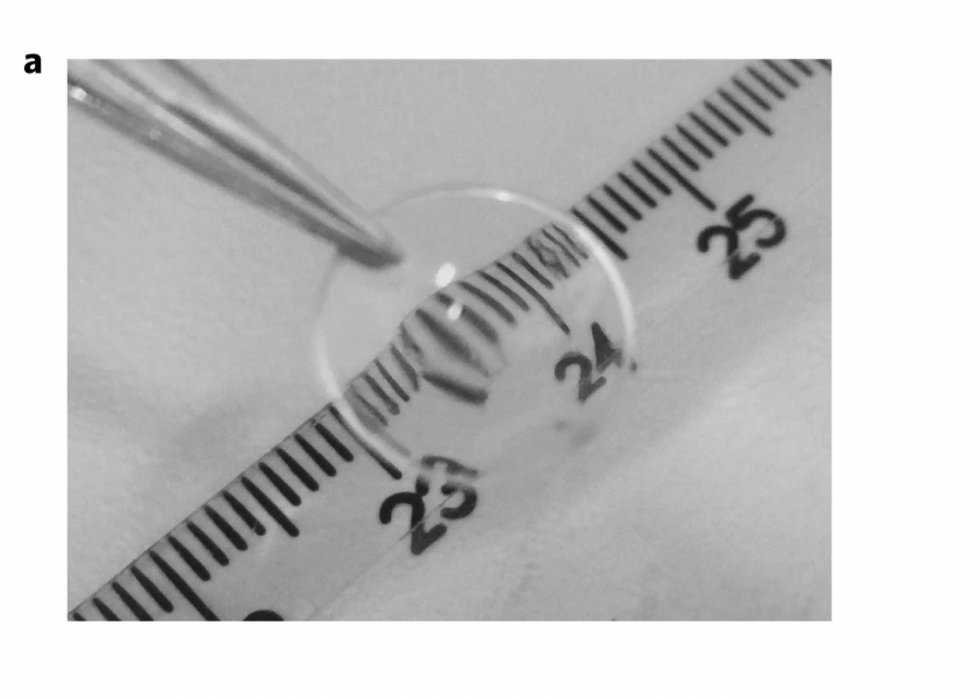

How scientists created the implants is cool too. Pig collagen was first liquified. This in itself is no easy task, as the material is “prone to degradation.” But after using the same techniques that keep collagen-based skin grafts stable, researchers created a transparent, implantable hydrogel that can mimic a human cornea. On first glance, it could be mistaken for a contact lens.

After surgeons make a small incision into the patient’s cornea, the hydrogel is inserted, which thickens the cornea and allows doctors to improve its curvature. The results, though varied, were dramatically positive. Meaning, at worst, some still had to use corrective lenses. And at best, some gained perfect vision.

Overall, this procedure could be cheaper, quicker and less invasive than traditional cornea implants. And perhaps safer, considering there were no adverse reactions experienced after two years following treatment. Neil Lagali, a professor of experimental ophthalmology at Linköping University in Sweden who co-authored the study, told NBC News, “There’s always a risk for rejection of the human donor tissue because it contains foreign cells. Our implant does not contain any cells … so there’s a minimal risk of rejection.”

There have been several technological advances allowing those with visual impairments to interact with their environment in new ways: apps that allow users to listen to, rather than view, a map of the world around them, smart glasses for both those who are blind and colorblind, even new legislation to make electric cars safer by mandating artificial engine sounds. Even Braille, arguably the oldest form of vision tech, has been given a modern spin with easy-to-use e-readers and electronic toys that teach Braille to preschoolers.

This innovation is yet another huge step for inclusion. According to CBS, Mehrdad Rafat, the researcher and entrepreneur behind the design and development of the implants, said in a press release, “We’ve made significant efforts to ensure that our invention will be widely available and affordable by all and not just by the wealthy. That’s why this technology can be used in all parts of the world.”

Science never ceases to amaze or move us forward.