Matt McCormick can still remember the sound his childhood basketball hoop made when the ball thudded against it. He describes it as a rumble, the result of the looseness of the cheap hoop, and a sound that even in memory can dredge up the anxiety of chasing a ball that ricocheted hard off the backboard down a slanted driveway before it had the chance to bounce onto any cars parked nearby.

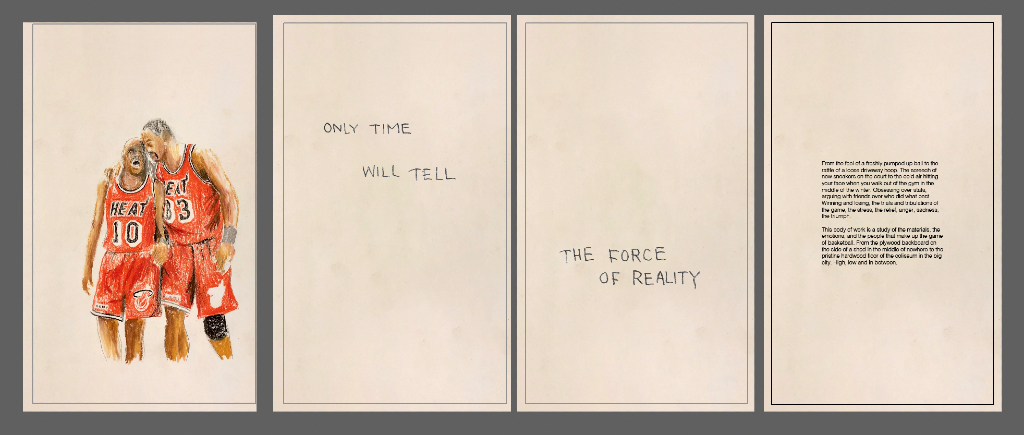

It’s a visceral memory many people who grew up as basketball fans can relate to. It’s also the heart of McCormick’s upcoming show during Miami’s Art Week, opening December 1st and running until the 4th. Presented in tandem with Bleacher Report’s Artist Series and the NBA, McCormick has created a space at The LAB in Wynwood in homage to his earliest memories of NBA fandom. One part traditional art show, with large-format paintings of the icons of his youth in Dennis Rodman and Allen Iverson, another part experiential installation in the form of a “sports bar dive bar” McCormick’s cobbled together from the places he frequented when he was younger, the show, he hopes, will ultimately create a bridge through NBA fandom into fine art.

“A lot of that stuff is a part of the foundation that we subconsciously don’t even realize is building the experience for us. All these different noises, touches, feel, smells, et cetera,” McCormick says over Zoom, taking a brief break from installing the show. “And I think that is a very integral part of being a fan that we may not even pay attention to until years down the line, when you’re like, ‘Oh yeah, I remember that noise the backboard made.’”

Growing up in the Bay Area, McCormick remembers the years when he and other fans were “just kind of dragged along” by a middling Warriors team. Lean seasons of fandom where a 2007 playoff appearance felt like winning a title, but otherwise a team no one would have predicted turning into the golden juggernaut of the West. But like so many other fans of his generation, McCormick had already been hooked by the larger-than-life Rodman and audaciousness of Iverson.

“They were tattooed, they were loud, they very much had a personality that extended to the way they dressed, the way they looked, and then just the way they carry themselves,” McCormick says. “And that to me was like highly influential as a young person. I’m covered in tattoos to this day, so I’m sure it had some effect on that side of it too.”

For him, they were caricatures of an American individualism. Tough, audacious, independent and alluring outlaws, all themes that would later come to stick in McCormick’s work with its Western motifs and American iconography — cowboys and their rearing horses, stock cars, old motel signs and Coke bottles, all dreamily collaged over canyon lands and open plains, aflame in the day’s last or early light. Those symbols and what they’ve come to reference, both in McCormick’s work and wider imagination, have parallels within sports, and certainly the NBA.

Line wolf players, relegated franchises, gunners and lights-out shooters — the terms we’ve coined as colloquial in basketball are borrowed from our broader, collective understanding of desperados but more than that, their expansiveness and sense of possibility. McCormick remembers the first work he ever had published, in Sports Illustrated for Kids, was a “made up version of a basketball team”. The cover of that issue featured Tim Duncan and David Robinson, meeting midair, both with basketballs in one hand and cowboy hats in the other, as a shadowed cowboy attempts to lasso their arms. An armadillo looks up from the ground at them in awe.

“And they were in, it was like them superposed in front of Monument Valley, which has become a huge part of my visual language in my non-basketball related work, so it’s kind of a full circle moment right there,” McCormick recalls, smiling. “So that’s kind of what I’m generally referencing back to is this kid, you know, trying to like learn how to be a man and a person and being obsessed with these larger than life characters.”

“Being a fan is more than just like what happens on the court,” McCormick says. “we kind of look to these people for everything.”

There are plenty of nods to that full-circle meeting of early fandom, in all its well-worn sentimentality, in his show, because McCormick was intent on distilling fandom down to its anchor points.

“Materials are highly important. It’s funny, I sat courtside for the first time recently and touching the court is almost like a religious experience of some kind. That’s why I love basketball so much,” he says. “All your senses are on overdrive. So the feeling of that court, the squeaking of a shoe, those noises. There’s a feeling of the wood floor, it’s so much different than say a concrete or asphalt court. There’s the differences between a metal chain link net versus a cotton net.”

Concentrating on materials, he wanted to channel the tactile and sensual elements of the game, and built four “pretty much regulation sized” backboards out of things like house siding and portions of an old boat. McCormick painted each backboard carefully — and quickly, over just one weekend — and purposefully, with homages to art that’s become the most influential to him in his practice, as well as his life.

“It was kind of a way for me to insert the new fandom for me, which has become the most important fandom in my life, and blend these two worlds where like, I grew up as a fan of this sport and now I’m a fan of this art, and how can we make the conversation come together,” he says. “I’m really excited about those.”

The hoops he sourced individually, and each have their own unique patina, reflective to real-life reps.

“They’re supposed to emulate the homemade backboard that you’d find on the side of a barn or something, like middle of nowhere. ‘Cause I find it fascinating, the reach of these sports, you know, you’ll have people in the inner city, and then you’ll have people like in the middle of nowhere, and there’s still the same kind of obsession and gravitation towards this thing.”

To house the work and cap off the sensory experience he’s aiming for, McCormick built a sports bar referential to the real thing as much as the dogma of them. He notes that within the duality of a dive bar — a place with its low points as well as one where everybody knows your name — there’s accessibility: they exist everywhere.

“But what is even more appealing to me is the decor, which is essentially anti-decor and anti-design. It’s basically building spaces of the most affordable, least considered, in a high brow sense kind of elements.”

McCormick, who became sober after his own bout with addiction, describes those elements with warmth. Fake wood panelled walls, Christmas lights that get left up, “and then what I love is the spaces kind of grow,” he says. “So it’s like the people that own the spaces, start acquiring, you know, what some people might see as junk, these of mementos. There’s family photos, some things are framed, some things are not. And there’s a real beauty to that kind of space.”

Creating a welcoming environment was crucial to McCormick when conceptualizing the show, and not just having it be free in contrast to Art Week’s exclusive tentpole convention of Art Basel. As someone who came to fine art in his own, roundabout way, he understand the barriers — both perceived and actual — in the art world. It’s why he’s so passionate about making and presenting art in a way that encourages people to come in.

“I think that one of the major problems with art and something that needs to change is this exclusionary mentality, because it doesn’t encourage people to participate,” McCormick stresses, mentioning the inroads basketball and contemporary art have made through artists like Tyrrell Winston, Jonas Wood, and the art basketball magazine turned gallery and record label, Franchise. But he also doesn’t knock something like basketball bobbleheads which, while people understand they aren’t getting a piece of art, do represent an entry point and “easy moment” for people to enjoy. Those little undulating figures spark something. Likewise, clothing with McCormick’s designs for the show will be available at the event, and online afterwards.

“Not to keep going back to those backboards,” McCormick chuckles. “but that was a big reason why I wanted to make this allusion to these artists that I find so important, so that someone could maybe be like, what is that about?”

Fandom, for McCormick and within the themes of this show, is an open avenue rather than something meant to be restrictive. It’s where his own practice sprang from, however unbeknownst to him then, flipping through a magazine with his art in it and a rootin’ tootin’ Tim Duncan and David Robinson on the cover. It’s where he learned, as a young punk kid reading the linear notes of his favorite albums, where the cool tattoo and skateboard shops were.

“And so if some kid who cares about basketball, but knows that it’s Art Week and this is all happening here, comes in and they have a moment anywhere close to that, that would be a win,” McCormick smiles. “I want people to love art as much as I love art, and I want people to love art just as much as they love basketball.”