Much has been written about The Menu (our review). Its cultural impact has truly been deep as food lovers (like me) recreate the iconic cheeseburger from the film while others note the possible influence it has had on the industry, with globally renowned chef René Redzepi deciding to close NOMA (again). Plus, it’s one of those films that seems to have made most critics’ “best of 2022” lists — means the discourse is just ramping up as we head into awards season. But one thing that feels like it’s been missed by most critics and the public discourse is the deeper meaning and theme of the film.

PLEASE NOTE: This post will 100% spoil the film. Head over to HBO Max and watch it first if you don’t want it spoiled.

While there are a lot of folks calling The Menu a remake of Ratatouille, that comparison is a bit flimsy. Yes, Ratatouille’s Remy has to let go of all his “training” and cult-like adherence to the dictates of a master chef and cook what he loves to be a truly great chef — the theme being “be yourself to succeed” which is true Disney fare. But The Menu’s Chef Slowik — the exec chef at the island-located restaurant Hawthrone — is already miles beyond that when we meet him. He feels victimized by the world of fine dining to such a degree that he’s going to burn it all down and take all the people around with him — not even Anton Ego in Ratatouille is that far off the deep end.

At the climax of The Menu, Margot — the sex worker who’s brought along at the last minute by one of Chef Slowik’s fanboys named Tyler (whom he actually loathes) — gets Slowik to cook him something he loves before he finishes his “masterpiece” of destruction. But cooking a beloved dish doesn’t change Slowik the way it changes Remy or Ego in Ratatouille. Instead, the theme that drives the The Menu is actually about re-finding pleasure through an act of service. The “Ratatouille” scene — if you want to call it that in the way the sense memory evoked when Chef Slowik cooks the cheeseburger echoes the sense memory evoked when critic Anton Ego tastes Remy’s ratatouille — is not a return to a childhood love of food for Slowik. Instead, it’s a return to the joys of pleasuring a customer.

Beyond the theme of hating particular customers to the point of wanting to murder them vs. a return to actually pleasing the customer, Slowik doesn’t have an arc in The Menu. Margot does, however — it’s her movie after all since she’s who we see first, last, and follow through the whole narrative. And it’s in Margot’s arc that the true crux of the movie lies. It’s about finally choosing to truly be part of the service industry (in this case, as a sex worker) and using her skills to help a broken-down old chef find one moment of true pleasure before he dies.

Like the old creep who wanted to be told he was “good” while he masturbated (more on him later), Chef Slowik just wants to be told he’s “good” not at cooking but at pleasing the customer.

PART I — THE SETUP

The film sets this up via the two exchanges that Margot and Slowik have on their own in the film (before the finale). The first one comes at about the 37-minute mark when Margot is in the restroom and Slowik accosts her. He bluntly asks her “I’d like to know specifically what you don’t like about the food. You’ve barely eaten any. Why? I need to know. Why don’t you eat?”

Margot replies, “Why do you care?”

Slowik comes back with, “I take my work very seriously and you’re not eating. That wounds me.”

This is setting up the finale in that it is teaching Margot (and us) that Slowik does actually want to bring people the joy of a good bite of food for real, not just show off his elite kitchen skills. It also draws Margot closer to Slowik with her literally opening a door that was between them and addressing him face to face (though still in a stand-off-ish manner — shouts to her for not being afraid of him for a second).

Slowik continues to interrogate Margot by asking “who” she really is and where she’s from for which Margot offers her escort cover story. Slowik senses this is a cover and straight up tells her “No, not who you want me to think you are. Who are you?” Margot holds to her story and there’s a moment of true concern on his face when Slowik says, “You shouldn’t be here tonight.”

Margot says, “Please, get the fuck out of my way” and the scene ends.

This whole ordeal sets up a ticking clock wherein Margot has to decide if she’s with the staff or the diners, i.e. a giver or a taker. More violence ensues. And finally, the ticking clock ends and Margot and Slowik take refuge from the chaos in his office so she can make her decision.

This scene, which is around the 55-minute mark (basically the mid-point of the film), is where Margot and Slowik connect in a way that demonstrates — or “foreshadows” if you want to get all screenwriter-y about it — the finale. Glass Onion does the same thing around the 33-minute mark when Ed Norton’s Miles literally lays out beat-by-beat how Janelle Monae’s Helen “disrupts” everything in the finale. (It’s a common trope, is the point.)

Margot starts off by telling Slowik what she thinks he wants to hear about her not belonging there and him being “brilliant.” Slowik asks her to cut the shit immediately with, “You’re not sure I’m brilliant so don’t say it. It’s false.”

Margot rolls her eyes and says, “Fine, you’re not brilliant.” To which Slowik almost hisses, “Oh, I expected more of you…” before softening with, “You belong here, with your own breed.” Margot asks what he means and he plainly says, “With the shit shovelers. Oh, you think I couldn’t tell? I know a fellow service industry worker when I see one.”

This starts to melt Margot’s facade and she sits down next to Slowik when he asks about another patron at the restaurant, “Mr. Leebrand.” Then Margot tells Slowik about her time as an escort for the billionaire (which sets up the “pleasure” of it all). Margo first tells him he liked to “jerk off” in front of her while holding eye contact. Then she goes into more detail about what he wanted her to say while “servicing” him as a sex worker. This is where Margot and Slowik connect in a “we’ve all been there” sort of way.

Slowik asks Margot, “Do you enjoy providing your services?” She takes a beat and replies, very honestly, “Yes. Or… I used to.” Then asks, “Do you enjoy providing yours?”

The openness between the two in this half of the scene is palpable as Slowik says, “Oh, I used to but…I haven’t desired to cook for someone in ages. And one does miss that feeling.” Again, the brilliant acting — little flourishes of half grins and even the tearing up of Ralph Fiennes’ eyes — helps this scene land as something real between two providers of a service.

This is also clearly setting up the finale, in that both Margot and Slowik are true-born service industry folks — providing their own brand of pleasure — who’ve lost their love for their game. It’s clear she’s barely putting up with Tyler’s shit during the first half of the movie (playing into her loss of enjoyment in her life). This is their connection and this is what Margot will give Slowik to allow her to escape later in the film. It’s the door she’s tasked with opening but she doesn’t have the key to open it just yet.

PART II — THE PAYOFF

The next sequence between Slowik and Margot isn’t private but lays the groundwork for the finale. Slowik tasks Margot with fetching a barrel from the smokehouse. The stern host, Elsa, disagrees with Slowik’s seeming trust in Margot and follows her as she breaks into Slowik’s cottage. After a struggle, Margot ends up killing her with a boning knife before returning bloodied and rolling the barrel into the kitchen.

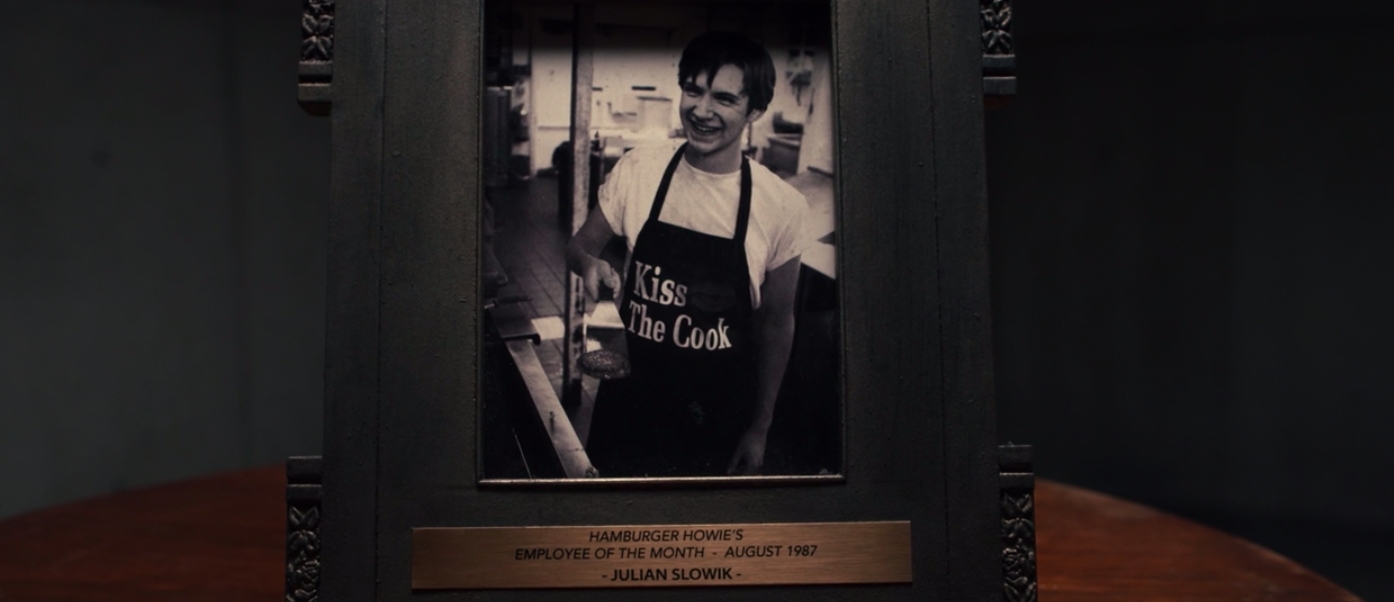

In between all of that, Margot spies an old photo of Slowik when he was very young. In the photo, he’s truly happy and flipping hamburgers at Hamburger Howie’s back in the late 1980s. This lovely little plant is paid off later and is the key that Margot needs to open up that lock and set herself free in the finale — though Margot doesn’t realize this just yet. In fact, she finds a radio and calls for help. Which is, of course, thwarted by Slowik’s well-constructed plan.

Still, that photo plays into the key theme of pleasure derived from serving people. A thing we know Slowik feels has been stolen from him. Even though each set of characters at the dinner seems unique as individuals (good writing!), to the chef they represent archetypes who have stolen his joy and love of the kitchen in one way or another:

- Slowik’s mother introduced him to cooking, which led him to his demise, essentially showing him joy/pleasure but leading to this all-encompassing pain.

- Lillian (the critic) and Ted (the publisher) suck the pleasure of cooking by making it for their own gain and bringing pain to so many who just want to nourish people.

- The finance bros funnel money into their own pockets instead of helping to create a system where the staff is paid a fair wage in the industry, creating the illusion of constant famine that rules the service industry.

- The “angel investor” uses money as a carrot and stick to commodify any pleasure of the people who love(d) cooking in the first place. And also trojan horse’s his “angel investing” into a more intrusive sort of partnership.

- The billionaire patrons only dine at Hawthorne to boast about their status.

- The food blogger/influencer who knows nothing about food but thinks he does because he’s watched Chef’s Table and performs pleasure when eating. Freaking Tyler.

Chef hates them all. Which comes out, either via tortillas (seriously) or Slowik flat-out saying it.

Then there’s John Leguizamo’s “Movie Star” who made a bad movie that wasted one of Chef Slowik’s only days off with a terrible comedy called “Calling Dr. Sunshine” (hilarious). Slowik wanted a moment of pleasure away from work but was instead assaulted with a terrible film that wasted his time and chance at having a moment of pleasure. So John’s gotta die — he represents an artist who doesn’t care, which chef can’t abide either.

The point of all of these characters/villains (in Slowik’s eyes) is that they’ve taken pleasure from him, and he’s had enough. This is all supported by a staff who’ve seen the same ringer destroy their dreams and pleasure and are ready to burn it all down too. Even the stabbing between Katherine (the female chef who stabs Slowik) and Slowik plays into all pleasure being drained from life via an awkward flirtation and rebuke. Every single turn in the script is about pleasure being destroyed or denied in one way or another. All of these side characters are simple window-dressing for that running theme.

At this point in the story, Margot has realized that calling for help is futile. So she starts to think of how to get out of the final course of this dinner from hell. You see her thinking, her wheel’s turning in her head as the camera inches toward her, and, finally, it hits her. The “I know a fellow service industry worker when I see one”; the “I haven’t desired to cook for someone in ages”; and the image of Slowik truly happy flipping burgers all lock into place.

She’s a service worker, a shit shoveler, so she jumps to work. Serving Slowik.

Margot stands up, claps like Slowik to get everyone’s attention, and tells Slowik the “truth” about his food and that he’s an obsessive. Slowik insists they/he always cooks with “love” and Margot calls his bullshit out. Both Slowik and we, the audience, know this to be untrue because he told Margot (and us) that he lost his love for cooking a long time ago.

Once Slowik is put in his place, Margot pivots to the service part of it all with a cutting, “And the worst part is that I’m still fucking hungry.”

This “wounds” him, truly. Then Margot really starts “servicing” Slowik to bring him pleasure. Not by looking into his eyes while he jerks off and saying she’s his daughter and that she loves him as with the billionaire Leebrand but by looking into his eyes and asking him to feed her and to be a customer that he can nourish with his “love.”

The scene plays out like a mini-play of a john and escort negotiating their terms before the act.

Slowik: “You’re still hungry?”

Margot: “Starved.”

Slowik: “Well, what are you hungry for?”

Margot: “What do you have?”

Slowik: “Everything…”

Margot: “Do you know what I’d really like?”

Slowik: “Tell me…”

Margot: “A cheeseburger.”

The camera moves into a close-up, Ralph Feinnes cracks a crooked smile of desire and says with a raspy, anticipatory voice, “We can do a cheeseburger.” She’s getting him off. Slowik cooks the cheeseburger with ease, because of course. But more importantly, Slowik cooks — something we’ve yet to see him actually do. Something he’s told us/Margot he’s lost the desire for.

Now, the desire is back and he’s loving it. He’s experiencing pleasure. His sense memory is firing (just like Anton Ego!).

Margot acts the scene perfectly by really laying on the fake joy of eating. She even giggles and moans as she eats like she’s watching someone finish in front of her. Look at his face when she says his burger is good.

He’s happy. He found that moment of pleasure that has eluded him for so long thanks to Margot literally servicing him. This is the face of a happy customer.

Thanks to the “service” that Margot provided, Slowik lets her go. She is truly a shit shoveler. She’s not a taker. She’s a giver to her core. This earns her her freedom.

From the sex worker’s perspective, the fact that Slowik’s pleasure is via a cheeseburger is nothing more than Margot figuring out Slowik’s kink and letting him get off on it. He flat-out says as much with a sly smirk after she challenges him to make a real, no-bullshit cheeseburger and he says, “I’ll make you feel you’re eating the first cheeseburger you ever ate. The one your parents could barely afford.”

He may as well be a john telling a sex worker he’s actually going to make her climax while she services him. It’s that on the nose.

In the end, though Slowik still kills the patrons (his cooks all commit suicide, as does Tyler — thereby allowing him to be “one of them” in death), this film isn’t a tragedy, really. Margot gets a happy ending by giving Slowik one last moment of pleasure. She plays the role she needed to free her and save her life — a role she was not as willing to play with Tyler earlier in the film because Tyler sucked and we all know it.

She truly became a shit shoveler and she has a damn good burger to enjoy for all her hard work. Also, she’s not dead.