It’s always bugged me that Matthew McConaughey had to play a rodeo cowboy dying of AIDS in Dallas Buyers Club to win an Oscar, when he’d already given one of the defining performances of an entire decade two years earlier. I’m speaking, of course, of McConaughey’s turn as “Dallas” in 2012’s Magic Mike, whose second sequel, Magic Mike’s Last Dance, opens this weekend.

I can understand audiences maybe not being able to fully appreciate Magic Mike for what it was in its own time. People showed up expecting a fun romp about male strippers with lots of dance numbers, and what they got was more like The Wrestler with pleather speedos. Male stripping and professional wrestling are both heavily kitsch, but both movies are about exploring and examining that kitsch for what it says and what it means rather than simply reselling it. I don’t begrudge anyone for just wanting to see the dicks shake (for those people, there’s Magic Mike XXL), but I also think that bait-and-switch is an acceptable strategy if you’re tricking people into appreciating art.

Magic Mike was a financial crisis movie. Steven Soderbergh (who directed the original and returns for Last Dance) was so unsubtle in making Magic Mike a financial crisis movie, in fact, that it’s only a testament to how good the stripping was that anyone could’ve been so dumbstruck as to miss that this was a financial crisis movie.

Magic Mike was set in Tampa, Florida, which is partly a semi-autobiographical reflection of the fact that ex-male stripper Channing Tatum grew up there, but also partly a reflection of the financial crisis, which hit Tampa particularly hard (to paraphrase Billy Corben, Florida has always been, first and foremost, a real estate scam). Tatum’s character in Magic Mike is an aspiring furniture designer who works in construction and owns a car detailing business, who moonlights as a male stripper. Partly for the money, but also partly because Dallas (McConaughey) has promised him equity in a future club Dallas he’s opening in Miami. “I want to hear you say the word,” Mike says to Dallas in their first scene together, “Equity.”

Basically, Mike wants to own something. Because what was the foreclosure crisis if not the event when so many Americans realized that the houses they “owned” were actually just rented from a bank? There’s a reason that one of the climactic scenes in Magic Mike is Mike trying (and failing) to charm a bank representative into giving him a small business loan. It doesn’t matter how much cash Magic Mike puts on the table, he still can’t trade it for trust or assets. His money is no good here; he can’t escape his circumstances.

Tatum plays the whole thing beautifully and I could write a whole separate essay here about how Magic Mike was the moment when Channing Tatum achieved the actor’s version of his character’s dream in the film — not just starring in it, but owning a piece of it. Producing his own semi-autobiographical starring vehicle that spawned a franchise. Not only was it a smart business move, it was good art. Every heartthrob and sexpot, or maybe just every heartthrob and sexpot’s agent, dreams that they’ll be able to hone their craft — through all the extra opportunities show business naturally affords beautiful people — and one day become real actors. It’s hard to imagine a starker example of that actually coming to pass than Channing Tatum in 2012, who went from a mumbly himbo we loved making fun of (C-Tates, as we called him on FilmDrunk) to two legitimately brilliant performances in Magic Mike and 21 Jump Street (on which he was also a producer).

Channing Tatum feels like everyone’s “local boy makes good.” Yet there’s a reason Magic Mike opens on McConaughey’s character. As both movie characters and public personae, McConaughey represented Tatum’s potential, realized. Casting is probably half of acting, and Matthew McConaughey as Dallas is one of the most cosmically perfect mergers of acting performance and public persona in cinema history. (Maybe the Academy voters just got confused when they gave him the Oscar for Dallas Buyers Club instead of for playing a club buyer named Dallas).

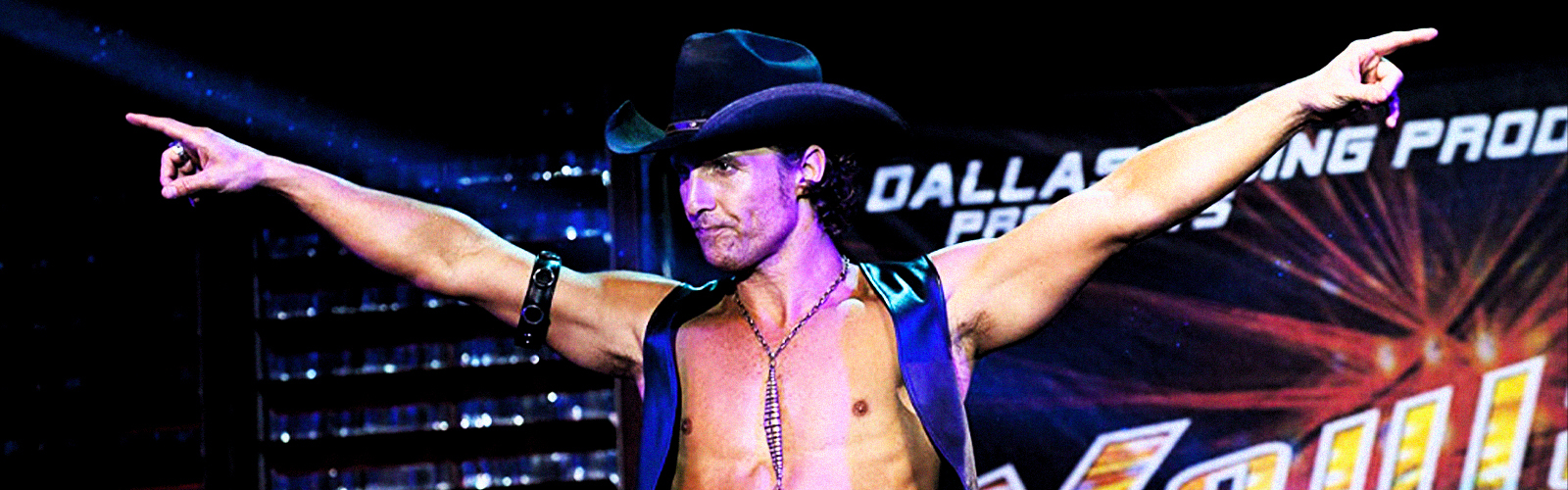

McConaughey, a one-time fresh-faced leading man (A Time To Kill) turned rom-com punchline (Failure To Launch?) turned dude known for playing the bongo drums shirtless, opens the film in front of a screaming crowd of women. The first shot of his face is him grabbing his crotch (in leather pants). He asks the crowd, “Can you ever touch this? Well, the law says that you cannot touch. …But I think I see a lotta lawwwwbreakers in the house tonight.”

Iconic. How many movie cold opens have ever gotten you as pumped as this one? McConaughey is not just a great actor and a great character, he’s a human redemption arc, the entire movie in a nutshell represented in a single man. McConaughey is 41 years old and dressed in a wide-open leather vest with leather pants and cowboy hat in this scene. You know how sometimes it feels like you can see smells? McConaughey looks for all the world like a guy you could smell from across the room in this scene, and yet somehow, not in an entirely off-putting way.

The cowboy thing is thematically important, and McConaughey’s drawl, coming from a born-and-raised Texan, is genuine. Magic Mike is a movie about a generation of men who have been, essentially, emasculated by an economic downturn, stripped of the things they’ve been raised to believe are the totems of modern manhood — homeownership, being the primary breadwinner of a household, qualifying for loans — attempting to become whole by acting out these kitschy, over-the-top parodies of masculinity: cowboy, construction worker, Ken doll, Tarzan. And they’re doing it in a profession that, essentially, they learned from women. The opening dance scene cuts on a sound, which turns out to buzz of Mike’s trimmer while he grooms his pubes. When he wears a shirt and tie onstage, it’s a kitschy joke and women through money at him. When he tries to wear a shirt and tie for real in the loan office, it doesn’t work. It’s still a joke.

The boys in Magic Mike are trying to become their idea of what a man is by being, more or less, male male impersonators. They’re all acting out “fake it till you make it,” both as a business strategy and as a lifestyle. Soderbergh and screenwriter Reid Carolin make this about as plain as it could be in a later scene when one of the other strippers describes reading Rich Dad, Poor Dad and going to a Robert Kiyosaki convention. Masculinity is a performance, and “The Kid,” played by Alex Pettyfer, hunky and appealing as he is, has to be taught. Naturally, it’s McConaughey’s character who does the teaching, in Magic Mike’s most enduring scene. If they’d played this to introduce McConaughey’s deserved Best Supporting Actor award on Oscars night, it would’ve brought the house down.

Again, in terms of looks, acting prowess, and public persona (the assumptions we carry into the film about McConaughey before he even says a word), I’m convinced that no other actor on Earth could’ve achieved quite what McConaughey achieves in this scene. He’s teaching The Kid how to perform masculinity, how to own the magical power of his cock and balls and seed (a power Dallas is trying to manifest into reality through sheer force of will), and doing it in a swim cap, spandex t-shirt, drag speedo, and jazz shoes. And he makes you believe. I didn’t even know what jazz shoes were before Magic Mike.

A lot of movies are about “daddy issues,” and Magic Mike isn’t not about those, but it’s more specifically about male mentorship — both the exhilaration and dubious nature of it. McConaughey is about 40, Tatum about 30, and Alex Pettyfer about 20. It’s easy to imagine that they’re basically the same dude at different points in the timeline. Every one of them is basically trying to convey what he’s learned about being a man to the generation just below, which is in turn coming of age in a place and time where not all of the previous generation’s wisdom may apply.

McConaughey in particular is able to evoke this with remarkable economy. Probably my favorite shot of the film is the one or two-second shot of McConaughey’s face when Mike first pushes “The Kid” out onstage for the first time. The Kid, not knowing exactly what to do, turns back to Dallas for guidance. At which point Dallas offers him a reticent, wary nod of conditional approval (the 00:27 mark of this video):

It’s a look of both fear and excitement, anticipation and trepidation. One that says “I know you’re not ready for this and I probably shouldn’t let you do it, but the universe has given you this moment, so sink or swim.”

Whatever your “scene” is, whether it’s music or sports or comedy or whatever, chances are you’ve experienced some version of this moment. I loved it when I first saw it 10 years ago and now I experience it on a few added levels as a father and stepfather. This theme, of trying to follow and set examples simultaneously, the exhilaration and terror of losing control, works doubly or triply well with the actors in Magic Mike. Because it’s true not only for McConaughey/Tatum/Pettyfer as characters in this movie, but also as actors and public personae.

McConaughey is the himbo turned artist in the midst of a redemption arc. Tatum is the himbo just taking control of his own narrative, and Pettyfer is the fresh face in his first blush of himbodom with a future still to be written. In a case of art predicting life, Pettyfer, just like his character in Magic Mike, may have learned the wrong lessons or just fucked up the right ones, and as of yet hasn’t quite had that second act. One of the complex emotions Tatum was surprisingly (at the time) adept at conveying in Magic Mike was Mike’s dawning realization that he might not actually be good for his protege.

Auteur theory says everything is planned by an all-knowing, God-like creator. I’m more of the opinion that true greatness requires more than a blueprint (and sometimes even happens at the expense of one). It requires a confluence of time, place, people, perceptions, and serendipity to come together just so in this unrepeatable way. A kind of “magic,” if you will.

Am I surprised that Academy voters overlooked Matthew McConaughey that year (when the award went to the admittedly brilliant Christoph Waltz for Django Unchained)? I suppose not. A good way to think about movie awards is that they’re essentially just focus groups by another name. If the voters were distracted by Magic Mike’s dick-shaking (its dick-shaving, its dick-pumping…), well, that was partly by design, wasn’t it? A bait and switch that worked too well. I don’t know if Matthew McConaughey’s performance in Magic Mike was underrated, overrated, or properly rated, but it will always stand out to me as an example of how great a great movie can be.

‘Magic Mike’s Last Dance’ opens this Friday, February 10th, in theaters everywhere. Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can read more of his reviews here.