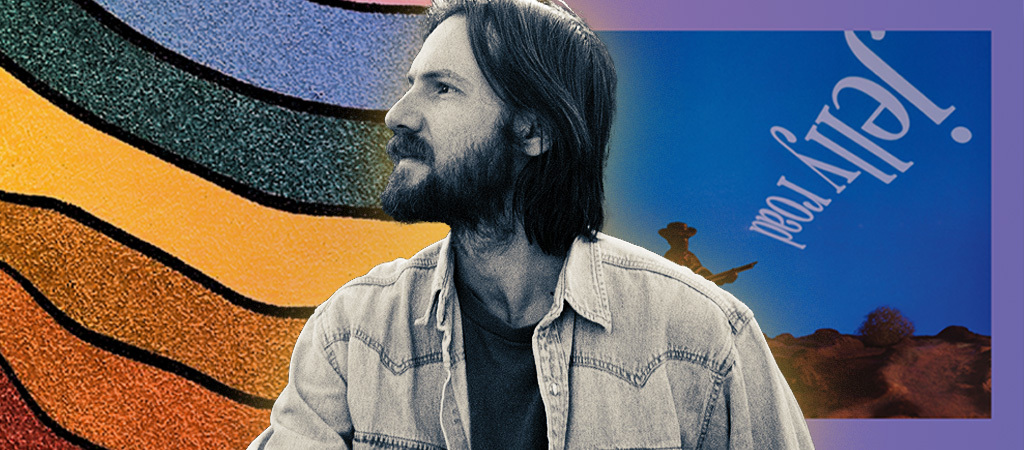

Blake Mills is the rare jack of all trades who also happens to be a master of many. Whether as a solo artist, collaborator, songwriter, or producer, the Los Angeles-born guitar virtuoso has become a singular force in the music industry. His recent work includes writing, performing, and producing the songs featured on Daisy Jones And The Six, which is how he connected with reclusive Vermont songwriter Chris Weisman, his co-writer on the new Verve Records release, Jelly Road. Mills first heard of Weisman during the Notes With Attachment sessions — his 2021 album with legendary bassist Pino Palladino — and shortly after inquired if Weisman would want to collaborate on some Daisy Jones music. Mills was expecting a pass from Weisman, but was hoping the connection would be fruitful down the road. Instead, the super-prolific musician agreed to work with Mills, and sent a dozen or so songs within a week. Very quickly, Mills knew they had music that wouldn’t fit the Daisy Jones scope, and thus Jelly Road was born.

This is how Mills’ world tends to work. He appeared on stage with Joni Mitchell at her concert at The Gorge Amphitheater in Washington, her first ticketed concert in over two decades. When Bob Dylan got ready to record Rough And Rowdy Ways, he recruited Mills to play guitar. Many of these connections come from Mills helming the boards at the studio he co-runs with Tony Berg called Sound City Studios in the San Fernando Valley. There, he’s become one of the most celebrated producers in rock. His credits include co-producing Feist’s Multitudes from this year, and producing Marcus Mumford’s Self-Titled and Jack Johnson’s Meet The Moonlight from 2022, Perfume Genius’ Set My Heart On Fire Immediately, and more. Mills has very quietly become a defining voice in rock and rock-adjacent music, attracting artists from all across the industry to his studio; as such, the world of left-of-center music sounds increasingly like the music Blake Mills loves to create.

In his spare time, he plays host to session staples like Sam Gendel and Abe Rounds. He’s built a community that is quickly expanding by the day, featuring any artist who wants to work with him and comes in with an open mind and willingness to experiment. As Blake Mills explains to UPROXX a few days before the release of Jelly Road (out today, July 14), recording with him is “more like a conversation and catch up, and almost invariably something wonderful comes from it.”

Ahead of release day, is your mindset different with Jelly Road versus something like Daisy Jones? Is there a different level of anticipation or nervousness? Or is it all bundled in the same realm?

There are definitely some differences between when you’re writing for a fictional character, or even when you’re writing for somebody else to be the performer. But what was interesting about doing the TV show stuff before this record was that there’s some freedom that I think you can allow yourself when you’re not the performer. You can be a little less critical of some things.

I don’t mean to say that you phone it in, but there aren’t quite as many drafts as when you’re making a lyric and you’re anticipating it being something that you’re going to sing yourself. I probably tweak a little bit more than I do if I’m co-writing with somebody and I’m making a suggestion, and I can imagine them singing it and imagine how it would sound coming through them.

But this record was also different from previous ones in that it was much more collaborative. So, there’s a co-writing element going on where you are passing something back and forth. That process alone makes it a little bit more outside yourself as well.

Is it fair to say you’re maybe a bit more self-conscious with your own writing, than when you’re working with other people or working on a hired project?

Definitely. I think there’s an element of self-consciousness, and there’s also an element of thinking on my solo records. Far fewer people are going to be hearing this than the audience for a Marcus Mumford record. So, yes and no. There are previous solo records I think I’ve viewed under the lens of more autobiographical for the most part. And then when there are songs that are not autobiographical, they still fall under the umbrella.

They’re viewed through the same lens as the other songs, or at least I’m perceiving that that’s how they’re going to be heard. So, there’s a mindfulness there. On this record, it was much easier to work on a song without fully understanding the literalness of the lyrics, for example, without knowing what we were writing about and just trying to access a certain feeling, as opposed to a certain story.

As opposed to your other collaborative albums — Notes With Attachment, for instance — was this songwriting process much different?

It was very unique in the way that having a conversation with somebody might be unique. The process, if you zoom out, might seem similar, but it has an organic sense of direction. It was unique from really anything in that way, as each record is. I think the nature of collaboration is something I find to be much more natural for me than the alternative, whatever you’d call that, the kind of monologue, solo statement, where I’m playing everything and writing everything.

Luckily, I’ve gotten to do that a lot over the course of my career. I enjoy collaboration much more. I feel like it’s easier to access things that are more interesting to me that way.

It’s pretty interesting how your solo releases have gotten more experimental. Break Mirrors, your first solo record, is pretty poppy and more straightforward than something like Mutable Set.

If you have a tendency to get hung up on something that’s a detail and you’re fixating on it, working with other people helps break that feedback loop. There’s a bit of a push and pull between the things that you might feel are worth your attention, and the things that they might feel are worth attention. I think the blend of those two end up creating something that’s unique, has a mind of its own or a personality of its own.

There’s something very inspiring when you’re playing with somebody or you’re writing with somebody, and something that they play or say resonates with you and feels like it’s a part of you…It’s like hearing your favorite song. There’s a quality to your favorite music that feels very personal. As I was saying earlier, there are aspects of Jelly Road that feel closer to me than anything I’ve put on a solo record before.

Did you know that when you first invited Chris Weisman to collaborate that it would work this well? I imagine there are a lot of sessions where you invite people you respect, or people whose music you like, to work together and it doesn’t always work out to the extent that it does here.

Honestly, when I reached out to him about the TV show, I thought he was going to pass, but maybe he would pass in a way where he would appreciate the invitation, and that we would just be in each other’s good graces.

It was an excuse to make contact with somebody who was notoriously reclusive. When he said he was game and actually really excited about the idea, that was when I actually started to formulate a more realistic picture of who he is, that wasn’t just based on reputation or what his music sounds like. When he sent like 12 songs a week later, I realized this guy is a fountain and it’s all over the place.

He’s one of the more eclectic artists I think I’ve ever worked with. I think he’s just an inspired individual, and is always writing and creative no matter what he’s doing. So, I quickly realized that he’s somebody who, in any setting, he’s probably not going to ever be short of ideas. It’s fascinating to just put him in different situations and see what he comes up with.

I think a lot of my career has probably been people doing the same thing with me, and maybe we relate on some level in that way, and maybe he can see that in what I do and find some kind of kinship in that.

Did you rely on the folks that you normally recruit for your records to play on this one? Or did Chris warrant different collaborators?

Bringing Chris coming out to LA, there was definitely something I was looking forward to with bringing certain musicians in, knowing that they were going to interact with Chris. He had already been in touch with Sam [Gendel]. They had known each other for a little while. Abe Rounds was somebody that Chris was aware of through me and playing with Pino [Palladino]. Larry Goldings came in because he was actually originally responsible for turning me onto Chris’s music.

When I was working on the Pino record, Larry just said, “You’ve got to hear this guy Chris Weisman.” So, that was something I was also looking forward to. The people on this record are less about an expectation of what they can add to the record or the music, and more about who they are as people.

Sam is full of so many ideas. The things that we didn’t keep from him you could make an entire record out of. There was no fear of, “Well, what if they come down and they’re not going to know what to play?” It’s not really how those guys operate, and certainly not how I operate.

It seems like everyone on this record is someone who brings joyousness to music.

When I’m calling somebody to come down and play something, it feels a lot like I’m calling them to meet up for lunch, not because I necessarily have a specific thing I want to talk to them about all the time. It’s more like a conversation and catch up, and almost invariably something wonderful comes from it.