Geoff Rickly was open to memorializing a $200-a-day heroin addiction, but not as an addiction memoir. That literary subgenre tends to subject itself to the same moral quandary as anti-war films – no matter how gory the action, no matter how high the body count, the mere process of turning it into art almost invariably ends up glorifying the very thing it claims to be against.

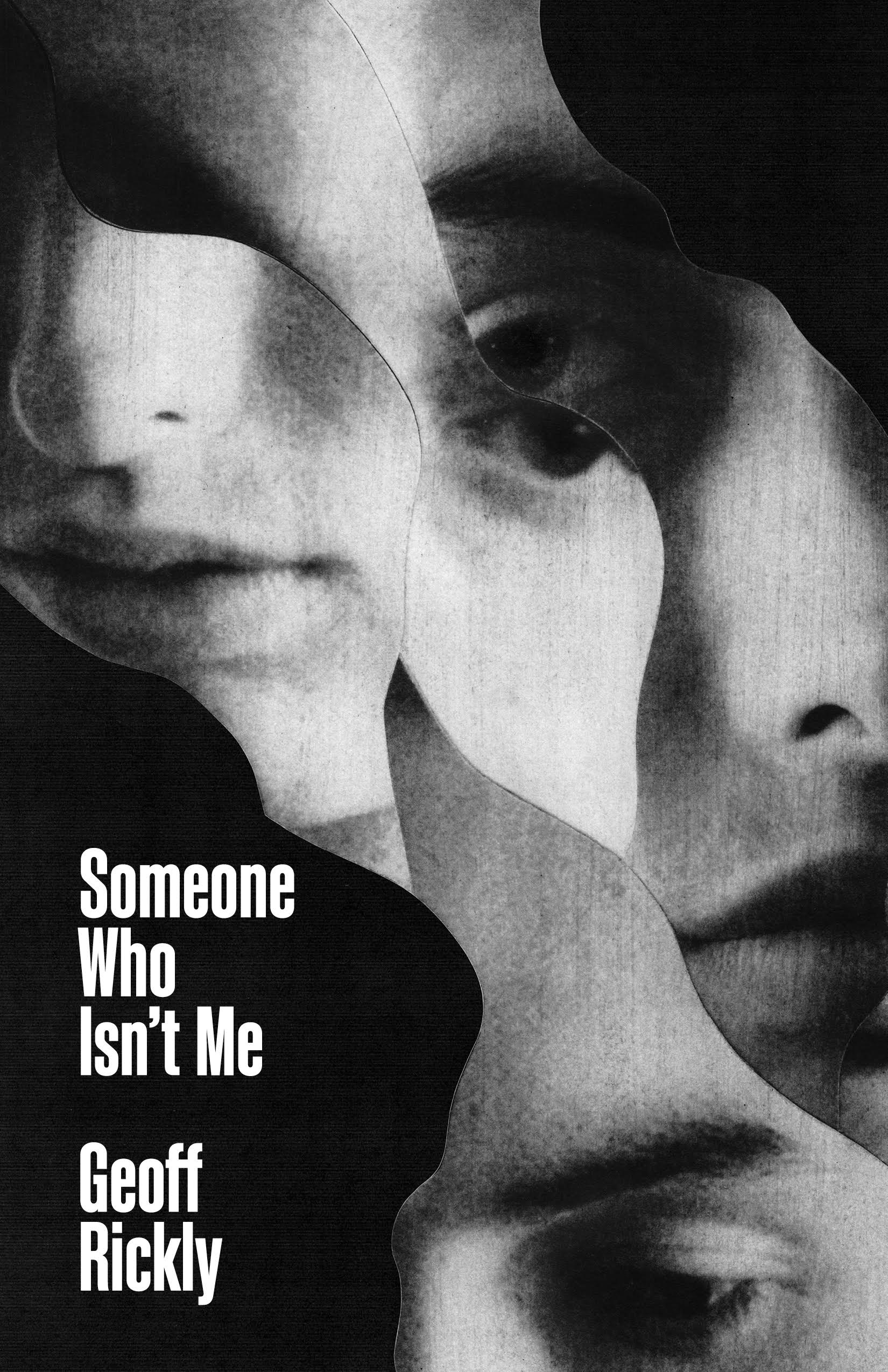

If the past 50 or so years of rockstar overdoses haven’t sufficiently dimmed heroin’s allure, I’m not sure Rickly’s debut novel Someone Who Isn’t Me will either. It’s not for lack of trying, as the autofictional Rickly hits many bottoms that are a matter of public record. For example, getting robbed at gunpoint while trying to cop, or sleeping under his desk at the Collect Records offices before it implodes in spectacular, public humiliation once Martin Shkreli is revealed as its primary financial backer; Shkreli indeed makes a cameo as a diabolical manifestation of Rickly’s self-loathing. I don’t recall ever seeing any news clip about Rickly fishing a bag of dope out of a clogged public bathroom, but I have to assume something sorta like that probably happened in real life.

The bigger challenge for Rickly lies in trying to avoid romanticizing the cure, which just so happened to be a Schedule I controlled substance in America. Both Geoff Rickly and meta-Geoff get sober after a weeklong, intensive clinic in Mexico where they ingest ibogaine – a psychedelic from the iboga shrub that has held promise as a cure for drug addiction since the CIA studied its effects in the 1950s. He compares the process to defragging the hard drive of personal memory, coming to terms with the most formative, traumatic experiences of your life while also seeing bugs crawling out of the wall. Also, after several days of group therapy, you smoke DMT with a shaman.

I could bring up the potential side effects, which include ataxia, cardiotoxicity, and, not infrequently, death. Then again, when has this might actually kill you ever dissuaded the most desperate drug addicts? In both Someone Who Isn’t Me and its related press cycle, Rickly is quick to puncture the substantial and paradoxical appeal of doing illegal drugs to cure an addiction to other illegal drugs. “You’ve seen the worst things you’ve done in your life and people get suicidal and start trying to call someone to pick them up in Mexico because they’re like terrified, like, ‘what am I doing here, these people are trying to kill me’,” he explains during our Zoom conversation. “It’s such a harrowing experience and when you come out of it, you’re like, ‘for real, you did that to me on purpose?’”

Someone Who Isn’t Me begins as a deceptively straightforward historical account of Rickly’s wilderness period, populated by his former bandmates, his real-life girlfriend and parents, and also, a loose network of drug dealers who speak in frightening deadpan. Certainly, Thursday fans will geek out as Rickly recalls the time he got a concussion swinging a mic Long Island-emo style and the tragedies that inspired “Understanding (In a Car Crash)” and “Counting 5-4-3-2-1.” But the emergence of Rickly’s authorial voice occurs in the midst of his ibogaine trip, a surrealist, vivid conflation of actual memory and dramatic license, part Sheila Heti, part Cervantes – a self-described tragicomic figure who truly believes he’s on a mystical quest.

The title of Someone Who Isn’t Me nods to the book’s meta angle, a preface used on Reddit’s drug-seeking forums where people (wrongly) assume it will provide them legal immunity. Writing in autofiction was a purely artistic decision at the beginning, similar to the way his band Thursday achieved massive influence and respect amidst the early 2000s Warped Tour scene by avoiding most of its cliches, taking a more oblique and literary approach to the genre’s tried and true subject matter. “If I tried to write a memoir where I just laid it bare, it would feel quite false to me,” he offers. “It doesn’t have that fictional element of what life had become for me.”

Moreover, it was intended as a savvy business decision: major publishing houses have saturated the “current events” section of Barnes & Noble with Opioid Epidemic explainers, while dozens of ex-addicts strive to write the next Cherry. Not that it initially worked out for Rickly. “Getting so many notes back [from publishers] like, ‘we already have one of these’ was such a devastating experience,” he admits. Eventually, his manuscript found its way to renowned essayist Chelsea Hodson, who appealed to Rickly’s DIY punk roots and made Someone Who Isn’t Me the inaugural release on her new Rose Books imprint. “She was like, ‘They don’t have any fucking books like this,’” he recalls. “I’m not saying it’s gonna be a hit, but they’re stupid – that’s why they’re the majors, because they’re stupid.”

The initial response has been overwhelmingly positive – the reviews, the presales and the publicity behind Someone Who Isn’t Me has far exceeded what Rickly imagined he’d ever achieve as a debut author on an indie press, though most debut authors never made Full Collapse. Indeed, much of Someone Who Isn’t Me owes its actual creation, not just its inspiration, to Thursday’s success; he couldn’t get much work done in his “get in the van” mode with No Devotion or as a solo act, “whereas when I’m with Thursday and we’re touring on a bus, I wake up and start writing, I can chill in bed and write.” But Rickly quickly retracts that image – nothing about the creative process of Someone Who Isn’t Me was chill for Rickly and nothing about being an author has been either. “I’ve been on tour with Sparta, I’ve been out with No Devotion, I’m out with Thursday, we were only doing festivals and now we’re doing a month of shows stringing them together,” he beams. “This was supposed to be my slow year, instead it’s just packed.”

Regardless of how “personal” your music has been portrayed as over the years, this book is likely the first time you can’t use plausible deniability – the narrator’s name is Geoff, Thursday and its band members are mentioned by name. Has it been more difficult to do interviews where you’re literally the subject matter?

With music, it can be quite personal and you are talking about yourself but there is a level of poetic license and blah, blah, blah. This feels, in some way, like the most nakedly vulnerable thing I’ve done, but I also think there are so many levels of fictional tissue paper laid over things. The life that I was living as an addict was almost fictional, it didn’t seem real. So writing a fictional book about this fictional life that I was having seems like the most real way to talk about the state of that life.

With so many people from your actual life in this book, were you concerned about whether they might be harmed by their inclusion?

Most of the people I included were either public figures or I talked to them – “You wanna read this thing before it goes out?” Not that I was going to change it, but they were all like, “it’s great, cool.” There’s a novelist who I really admire, Juliet Escoria, she wrote this book Juliet The Maniac, and I was able to get her to blurb my book. It’s a fictionalized novel about a girl living with, and understanding, a schizophrenia diagnosis in high school. It was a huge inspiration for me, I love the way she wrote it and the way that she dramatized inner states. When you’re inside them, it’s not “what you have is schizophrenia,” it’s like… “okay, now there’s black lines moving down the hallway.” I really admired how she was able to put you there inside, how the book was so beautiful and poetic and made me understand a state of being that I couldn’t imagine. I loved it so deeply and it gave me credence – I can do this, I can figure out how to dramatize this thing that is both real and also fictional. But with the fictional part, how do I portray it in a way that’s experiential?

Memoirs don’t make you feel like you’re in it, they explain it to you. I wanted to make people feel like they’re in it and can understand and empathize with it. So when I finally talked to her, and asked “why didn’t you include this thing in your book,” she said, “I wasn’t allowed to, [my lawyer] said it was too close to reality, I had to change it.” Chelsea’s lawyer didn’t tell me to take this thing out! We’ll see! We’ll see who’s got the better lawyer! More will be revealed about whether I needed better clearance, but on a moral level, I feel pretty good about it.

There’s a romantic ideal young people have of authors – particularly experimental writers inspired by drugs. How did the experience of being a sober, 40-something author compare to the one you had as a teenager?

When I started the book, I figured I should get an old typewriter, do it the old-fashioned way by hand and get a blazer with elbow patches. There was definitely the romance of writing, and the reality of writing hit me in several stages – first of which is that I do my best writing in the morning as soon as I get up. I need to give this book five hours a day in the morning, every day, five days a week and some weekends. Steadily, I gave the book five hours a day, five days a week, for five years. That’s a lot of hours for one piece. I can sell it probably on the same margins as a record and I can probably make a record working five hours a day, five days a week, for two months and be done. It would be done and it’d be sick, I know that experience. I’ve been there, I can confidently say I can make a good record in those two months, so this is a lot more time. I had to learn a new craft, I had to go back to school so to speak. I took classes, I took on mentors and I read books and listened to Masterclasses. I really studied. I got an agent and she gave me huge reading lists, and I read 50, 60, 70 books that my contemporaries were doing that she thought were comparable in style. And I made notes and tried to understand what their project was doing and how they accomplished it, I looked up notes of the interviews.

The most helpful note I got in the space of what I could do in autofiction was after reading Sheila Heti, she said, “If you can show me where the funny is, then you know where everything is.” It’s gotta be funny, it’s gotta be funny! It’s not gonna be a joke book, but I gotta find what the humor is in my situation. Luckily, I was able to find the Don Quixote character who believes himself to be on a holy quest but is actually the fool. I can make that funny. I’m the first person and you see my point of view, but you can also understand that point of view is limited by his drug use to where he only sees within the blinders and everyone else sees him clearly. I can dramatize this in a way that can be funny – the difference between what the narrator sees and what every other character sees and I think the reader will pick up on, “Oh man, the narrator is trying to tell me how it is but he doesn’t know how it is. He’s lost, I can see it.” There’s also the reader feeling a little bit superior to the narrator, “Oh man, what a fool.”

I’m curious about how you were able to recreate the ibogaine experience, were you allowed to keep notebooks during the procedure?

So your limbs don’t work when you’re in the care of the ibogaine clinic, your ataxia is so extreme that even lifting your head isn’t a good idea. The whole room spins, you lose control. Like, getting people to the bathroom, I watched other people go and when I had to go, it was a nightmare. So writing was impossible, there was no way to keep notes. It was a very vivid experience, like nothing I’ve ever experienced in my life, so in that regard, it stuck with me. I decided early on I would take huge liberties with the trip and I would substitute hallucinations for fiction. So instead of being psychedelic, it’s surreal.

How would you describe the difference?

I think psychedelia is more experimental, you can see it in the text with how it fractures and fragments, whereas surrealism starts in realism and bends slightly. So rather than being an onslaught of imagery that you can’t make sense of, it’s this slow bending of reality around an emotional state. The first part is the closest we get to memory and I took liberties putting memories in there instead of what I saw on the trip because I thought I could tell this story in a more linear way. The trip itself was very chaotic and a lot of pictures, stuff that no reader would want to sit through. The truth itself [of the trip] was “now there’s bugs, now there’s this, now there’s that.” So I decided this middle section is going to be more epic and the next section is going to be about the emotional truth of places. Like, I’m gonna try to model it after Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino.

Did you have any experience with psychedelics before this one?

In high school, I had several pretty heavy psychedelic experiences. The biggest one was when my high school girlfriend was like, “We have a half day of school on Friday and I got us mushrooms, so let’s take them and chill out together.” And I was like…“Okay!” She was going to meet me at my house, it was maybe 11:30 AM and I took my half and was waiting for her. And she was like, “Hey, uh…I can’t come today, I got called into work.” What do you mean, I already took my half of the mushrooms! And she’s like…“Half? You know that was for four people, right?” I tripped so hard, I went through a full death-and-rebirth process and had full-length mirrors where I thought I found spirit guides. I thought, “Oh, I’m invincible now, I’m gonna take acid,” that kinda thing. I had been a little bit down that road before but it’s not my preferred method of being, I’ll tell you that much.

It’s well known that Bill Wilson [the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous] believed that LSD could be used in the treatment of addicts and had taken supervised trials himself when it was still legal in the 1950s. Still, do you have any ambivalence about using this type of drug as a cure for drug addiction?

I was looking into [going to the ibogaine clinic] for a year. I had a friend who confronted me with it and said, “This is probably the only way you’re going to get it,” because we lived together for a while and he watched me struggle. After being like, “No this is stupid, I wouldn’t take a drug to cure drugs, I’m going to do this the old fashioned way, going to meetings high or copping after a meeting,” I started to really think…I am those unfortunate few that are constitutionally incapable of being honest with myself. Oh shit, I guess I’d better take the most extreme course of action. That was it. I can’t do anything more extreme than this and it scared me senseless. It’s so scary, some of the documentaries show a ritual practice in Gabon where they’re force-feeding people so much iboga shrub bark and the person is throwing up and being dragged through a puddle and their head is dunked in water and people are blowing smoke in their face…I don’t want to do that! I didn’t think there’d be people who’d make sure I’m OK, but they’re gonna give me an IV to stay hydrated. It was a tough decision but I think it speaks to how, by the time I went, my friends and family were like, “What are you gonna do man, you can’t stay here any longer. You go do whatever, because there’s nothing for you here.” When you get that from your friends…“Oh, it kills some people? Yeah… well, you’re definitely gonna die, so you better go.” [laughs]

There’s a great bit in the new John Mulaney special where he jokes about going to rehab and being kinda disappointed that no one recognizes him. Was there anyone in the group in Mexico that knew you were a musician?

I did get close with the other people and learned about their lives, they kinda knew that I was maybe a musician. After the DMT session where everyone’s crying and smiling and I started believing in god – which is a pretty intense experience – we were sitting in a circle and they gave everyone little things, like a fruit juice. They blend strawberries and you’re like…“Oh my god, this is the best, I can actually taste what fruit tastes like, fruit is amazing.” You’re having that experience together, “Look at the sun, look at the beach! Why were we so upset last night, the world is so beautiful!” And I noticed for the first time, there’s an acoustic guitar and I picked it up and played a song. None of them knew Thursday. I played a song I wrote or whatever and I was in it, it was especially vivid. And they were like…“Wow, you’re a musician like that? You’re a real musician?” That was a really cool experience for me because sometimes I think all of my success is based in the cultural context of the early 2000s and the way we changed certain things to an extent. I’m sure that’s true. But I don’t think of myself as having talent of some kind. I don’t think, “Oh, you’re actually good at this and you have a gift for communication through song,” but that moment was one of the first times I realized I do this because I love it and I am good at it. It changed the way I thought about myself.

Do you still keep in touch with any of them?

We kept in touch pretty regularly for the next year. The woman in the bed next to me who said that she saw Cleopatra [during her trip], she came to see Thursday play at the Roseland Ballroom in Portland. She was like, “Fuck yeah, that was awesome!” She was also really drunk and I was worried…“Oh no, is this ok, is this bad?” I’m doing 12 steps now, so I’m kinda sobriety-pilled so to speak, you gotta be 100% completely sober. We haven’t kept as much in touch since, I know not all of them have stayed sober but I think any method is gonna work for some or not for others.

Is the sole purpose of the ibogaine clinic necessarily to help people achieve sobriety or is there a component of simply trying to “expand people’s minds” or help them develop a clarity about their lives?

There are different ways to look at it, there’s a 7-day program for addicts to get clean and there’s a 3-day program that they were offering for C-suite executives to have an experience and…learn how to master the world. “You wanna know the truth? Check this shit out!” For me, it was, this has to be it. And to that extent, as long as I was looking at it like “This is the thing that has to work and I don’t have any other chances,” I had that gift of desperation that people talk about is so important.

Given how it worked for you, do you feel compelled to advocate for mainstream acceptance of ibogaine?

This is gonna maybe sound bad and I don’t mean it to be. But I think a few years ago, MAPS or one of the other psychedelic centers that are interested in the research potential might have been like, “Yeah, there’s potential here, why aren’t we doing this?” Whereas now, there’s more of a political angle to the promotion of psychedelics. “We’re really close to making psilocybin work for X amount of people in a clinical setting in the US…if we can get this done, let’s normalize it and make it sound safe and effective which it can be…but let’s not muddy the waters with this fucking 36-hour space odyssey and maybe it kills some people type of drug.” The psychedelic community might say, “Let’s be quiet about that one, alright – that’s not gonna help us right now.” That’s understandable and unfortunate because I think there is a potential and we’ve known since the 1960s about that potential. There’s a doctor, Howard [Lotsof], he was able to cure his own heroin addiction with [ibogaine] and realized how powerful it was and wrote to Eli Lilly and applied for a patent. And Eli Lilly’s like, “You’re using what? It’s not really worth it for us, how much will we charge to make it worthwhile, we’re working on methadone or whatever.” I don’t remember all the specifics, I’m not trying to smear Eli Lilly, it was that kind of response. “I don’t really see where the potential is for this drug to be profitable or work in a way we need it to, it’s too uncontrollable. We have this thing where people can see us every week and we can keep an eye on them, you know?” I do understand the clinical angle of wanting to keep an eye on people when they’re getting treatment, it’s not stupid.

I suppose there’s also the moral stigma attached to drug addiction, that people wouldn’t want to have something as simple as a pill that could cure it.

Even the resistance to harm reduction like Narcan – how can you be against Narcan when it saves people’s lives? “It’s saving the wrong people’s lives!”

Bands will often talk about how much easier making a second album is after they’ve spent years figuring out how to do the first one, do you have that sense after completing your debut novel?

I’m working on some short stories, I got a few people who’ve asked me for them, it’s just so different. I wrote this book, which is such a specific thing, and now I’m like, what’s writing in third person like? There’s a learning curve, and I’m trying to figure out what the next idea for a book would be, something that captivates my attention enough that I would throw myself into it. It’s quite a commitment, I’d better be interested in the subject matter. This is a great situation but I’m like…maybe I can get the next one on a major, because then I could get a starred Kirkus review and “staff pick” in Barnes and Noble or some stupid thing that I don’t need. I talked to Sam Tallent, who blurbed my book, he wrote this amazing book called Running The Light, he self-published and sold I think 100,000 copies and he had the #1 Audible audiobook…and he said, “But all I really want is acceptance in the literary community.” Dude, you’re making a living writing, everyone that’s “accepted in the literary world” wishes they could do what you’re doing!

In the parts of the book where you recall writing music in Thursday, the importance of collaboration and immediate feedback is very clear. How do you recreate that element of the creative process into something as solitary as writing a novel?

I wasn’t [getting feedback] on the bus, but I was in a workshop on the 92nd Street Y, which is sort of a famous New York institution for writing. I got a lot of critique, some it was very good, some of it was like…nah, you’re clearly wrong [laughs]. But even getting clearly wrong advice was helpful in being able to evaluate feedback. In the beginning, I needed a lot, I kept telling my agent I usually have a band member who’ll tell me, “That sucks.” And she was like, “I’m your band member, you got a question, hit me.” And when I found Chelsea as my other band member, I’m like I got the sickest band now. Power trio!

Do you read your own reviews?

I always read the reviews. When I was younger, I was probably too sensitive and I shouldn’t have read them all. But I just think if there’s anyone who is a smart, thinking, caring person who engages with your art, I wanna know. It’s important now that I have some self-respect – “I can see why you would want that, but I’m gonna do what I need to do. Respect.”

Literally everything I’ve seen about the book has been positive so far.

It’s been really surprising because Thursday really had to fight for any kind of respect and having people be like, “Yeah, this is good” is weird. Okay, I’m new to this, shouldn’t you hold my head underwater until I can’t breathe and then be like, “Okay, you can get up now?” I guess the other shoe isn’t gonna drop? Hopefully, we’ll see!