When making movies, Michael Mann doesn’t compromise. And judging from his filmography, I tend to believe this is true. (I even love The Keep, a movie that is not Mann’s favorite.) Though my point was more the compromise of having to wait a few decades to get Ferrari made the way he wanted it made, but, as Mann points out, this is semantics. And this is definitely true.

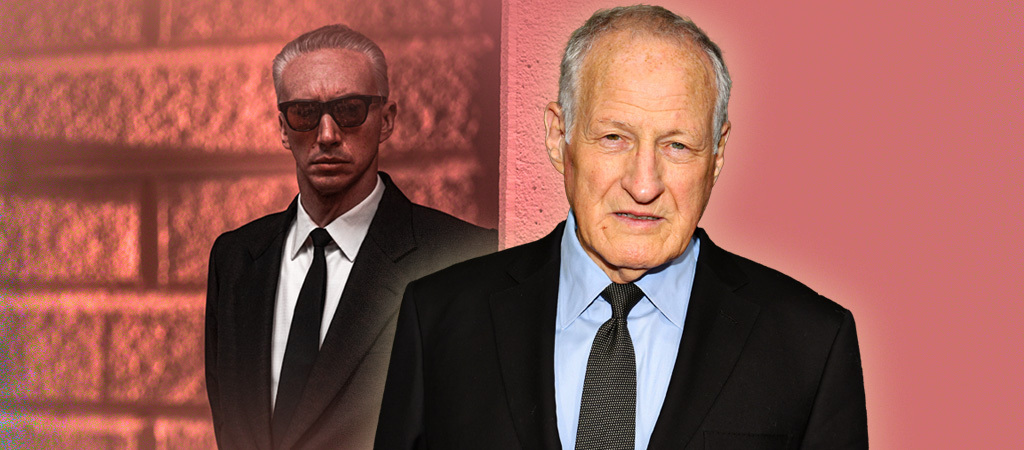

In Ferrari, Adam Driver plays Enzo Ferrari, a man obsessed with making race cars, hiring race car drivers, and winning races. It’s hard not to see the parallels between Enzo Ferrari’s drive and Michael Mann’s drive – to the point Mann even halfheartedly agrees with this. Mann has been wanting to tell Ferrari’s story for decades now, but it had to be on Mann’s terms and Mann has finally derived the film he envisioned. Ferrari himself is a complicated individual and the story is not anywhere near a traditional biopic – focusing on Ferrari’s obsession with winning the Mille Miglia in 1957; the last year that race was ever held for reasons the movie explores – but would anyone expect a traditional biopic from Michael Mann? Also, Mann is a long way from being done as a director, listing off a litany of projects that we know about like Heat 2, and some we don’t really know about when he mentions he wants to make a sci-fi movie.

I kept thinking this while watching Ferrari, do you think there’s a connection between Enzo Ferrari trying to build a perfect race car, find the perfect driver, and you trying to get this movie made after all these years? I feel like there’s a parallel there.

Well, it’d be nice to draw that parallel, but probably the only… I think it’s just the fact that maybe there is a parallel, but it’s the fact that whether you’re making a movie or wanting to have a race team that’s succeeding – or if you’re an architect and you’re trying to build a building – it’s the same thing. You have an aspiration that’s dependent on some other people’s money.

That’s a good point. Enzo makes compromises to get what he wants. So I keep thinking, probably all your movies, the compromises you have to make to get what you want and like him you don’t make a lot of them, but when you make one, they’re about as perfect as they can be. But maybe I’m off base…

Yeah, I don’t make many compromises. The reason it took so long to make Ferrari is because I had opportunities to make it years ago if I wanted cut back the concept; cut back the imagination of what the film should be. And I decided I would only make the film if I could make it the right way or I wouldn’t make the film. So that’s one of the reasons it took so long. Because it could have been independently financed as a $35, $40 million dollar movie many years ago, but to do it the right way, there are a lot of hard costs like building the leather replica cars, for example. And so it had all be done right or I wouldn’t do it.

Waiting all these years to get it made is still sort of a compromise, with yourself…

That’s kind of semantic. It’s not really a compromise. Usually, there are a number of movies I want to make and I make those, but the nature of it is you want to make something and you can’t make it right now, but you can put it aside and go off and make The Last of the Mohicans, Heat, Collateral, Ali, The Insider. Out of those movies, I wanted to make them just as much as I wanted to make Ferrari. It’s not something you just want and you’re in a constant state of desire. What hooked me into Ferrari was the quality of the story. And so every time I thought, “Why don’t I just abandon this?,” I’d open up that screenplay and get to page two and got hooked into the people’s story all over again. But I also wanted to make Ali as much as I wanted to make Ferrari, as much as I want to make Mohicans and Heat and everything else.

And I know you were involved with Ford v Ferrari, and I read the interview where you talk about the differences your version would have had. I’m curious, if that actually happened, do you still make this one? Or would that have been your Ferrari movie?

I don’t know. That’s a really good question. I really don’t know what would’ve happened if I had made Ford v Ferrari. Ford v Ferrari and Ferrari both have one singular virtue: They’re very good stories. And the reason that movies that are in any way related to racing have never worked before, meaning that they weren’t successful – think about Grand Prix and Le Mans. There’s a lot of great work in it, but they’re really lacking in a fantastic story and the benefit of what Jez Butterworth did for Ford v. Ferrari is that, at the core of it, it’s a really great story.

But it does sound like this is the story of Ferrari you wanted to make, even though they’re both great stories. Is it better that it wound up that you didn’t make Ford v Ferrari?

Yeah, I think so. It’s a funny question because, I don’t know, I would’ve made a probably different Ford v Ferrari. I was very taken with the story of Ken Miles. That’s the story of Ford v Ferrari and the evocation of his life, which I found really interesting. But just comparing apples and oranges, I mean, they both exist simultaneously at the same time. They’re different and you put yourself into one thing, you put yourself into something else. I want to make something on the Battle of Wai in 1968 during the Vietnamese war. I want to make Heat 2. There’s a science fiction film I want to make…

Oh, what’s the science fiction film you want to make?

[Laughs] I can’t talk about it!

Watching this, you work so well with Adam Driver it feels like you’ve worked together, before, but you haven’t. But all your movies kind of feel like that. Other than working with Al Pacino and Jamie Foxx twice, you really don’t work with the same lead actors often.

You cast a movie, you cast a movie for the actor. Who’s the best actor if he’s going to play this part? Will they inhabit a certain character? And that’s the decision you make. And it has to be new every time. You don’t work with people out of… you have friends. I mean, I’m as friendly with Daniel Day-Louis today as I was when we were doing Last of the Mohicans. But each time, the authentic way to do this job is to find the actor who, if he embodies this character, is going to work within that narrative in the most powerful way.

I feel a lot of filmmakers do that. And I think it’s why your movies feel so unique.

What, just working with your friends?

Well, you said you cast who would be best in the role. And I don’t think every director does that.

Sure. Well, the way I do it… it’s very, very difficult, by the way, you’re talking about. I mean, I have a cameraman who’s my close friend. We’ve done four movies together. But he may not be the right cameraman for this next movie. And he has to understand that I have an obligation to the movie to do the best I possibly can. And that may mean not using him. And if that’s a problem, then he is not your friend. So that’s something that happens. That happens frequently.

You can contact Mike Ryan directly on Twitter.