First Attempt: Noah Kahan Is Interesting Because I’m Writing About Him (Probably) A Little Too Late

“Have you heard of Noah Kahan?”

It was May of 2023. My editor was quizzing me on Slack. I was not prepared.

“No.”

“Look at the billing this guy is getting.”

My editor shared a screenshot of the Austin City Limits Music Festival poster. On the left side of the poster were the headliners, listed vertically: Kendrick Lamar, Foo Fighters, Mumford & Sons — all the way down to The 1975 and Hozier. Then, to the right in a big block of horizontal lines packed with text, was “this guy” at the very top, between the singer-songwriter Maggie Rogers and the British rapper Labrinth. This was, indeed, a very notable billing for some dude I had never heard of.

I punched the words “Noah Kahan” into Spotify. “His streaming numbers are strong,” I Slacked back to my editor. I clicked on one of his songs and gave it a half-listen. “He’s very much in the Hozier/Lumineers vein” was my snap judgment.

“That kind of crap is always popular,” I deduced.

My editor replied that none of the other people he asked about Noah Kahan had heard of him either. “Apparently his fan army is called the Busyheads,” he said.

“Gag.”

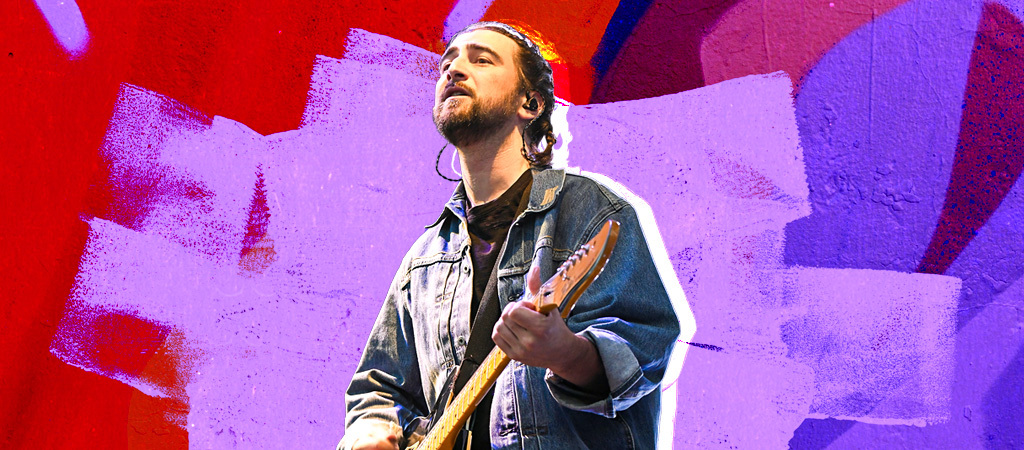

After that, things got pretty catty between me and my editor, as things do when you’re commiserating online with a co-worker about a successful though seemingly under-the-radar folk singer. Let’s just say that we both expressed unkind sentiments about his music and the earnest demeanor of his press photos, which depicted Mr. Kahan as a “soulful nature guy” type with long black hair, a black beard, and quietly intense dark eyes.

“This kind of music seems particularly prone to this sort of phenom — twee/boring folk singers who are secretly huge,” I typed. “The kind of shit nobody likes to write about and tons of people like to put on in the background.”

Looking at these Slack messages eight months later, I still (kind of) agree with them. But I was also clearly wrong. Because here I am, somebody, writing about Noah Kahan. Worse, I’m writing about him (probably) a little too late.

Better late than never? Let’s see how well the rest of this column goes.

Second Attempt: Noah Kahan Is Interesting Because He’s Huge

He was already huge in May of 2023. But he’s even bigger now. And he is going to continue growing enormously throughout this year. I just know it. It feels inevitable. If there is one thing I know about Noah Kahan it’s to never underestimate his potential to grow enormously.

Have you heard of Noah Kahan? He’s a 27-year-old singer-songwriter from Vermont. Up until very recently, Kahan fell into a category I refer to as “popular but not famous.” These are artists who are not generally recognizable to the average person because they haven’t been publicized by the mainstream media. But when you look at their streaming numbers you realize that they’re somehow ranked among the most successful musicians in America. (The inverse is “famous but not popular,” which applies to acts that get a ton of press but don’t have a big audience. The kind of artist that used to be described as a “critic’s darling.” Stephen Malkmus is the anti-Noah Kahan.)

Kahan currently has 33 million monthly listeners on Spotify. That’s 13 million more than the Foo Fighters, one of the top headliners on that Austin City Limits poster my editor Slacked at me. But that’s only the beginning. This guy is no longer “popular but not famous.” He’s getting to be popular and famous. Kahan’s 2022 album Stick Season has gone platinum, and the expanded 2023 reissue slotted all 18 songs on Billboard‘s Hot Rock & Alternative charts. The album is currently lodged in the Top 5 on the Billboard 200 albums chart, and the title track is moving toward the Top 10 in the singles rankings, nearly a year and a half after it was originally released. Last month, he was the musical guest on Saturday Night Live. Next month, he’s up for a Best New Artist Grammy. Given the kind of music he makes — plucky, tasteful, and aggressively uplifting folk rock that is to Mumford & Sons what Bob Dylan was to Woody Guthrie — there’s a strong chance he will win the award.

Oh, and you should look at the billing this guy is getting at music festivals in 2024. (Or his upcoming tour of arenas and stadiums, which is so big it has created a Taylor-esque Ticketmaster crisis.) If you are planning to see live music in a large field packed with sunburned Zoomers this summer, you will likely have Noah Kahan in your life.

Third Attempt: Noah Kahan Is Interesting Because He Explains How Music Gets Popular Now

Here’s a joke: A music critic is found brutally murdered in his apartment. Two detectives show up to investigate. In desperation, one of the detectives asks the music critic’s pet parrot if it saw anything.

“Because of TikTok! Because of TikTok!” the parrot says.

The detective is confused. “This parrot thinks that TikTok murdered his owner!”

The second detective shakes his head. “The parrot is just repeating something he heard a music critic say a million times.”

The point of the joke is obvious: Music critics in 2024 love to give TikTok credit for everything that happens in pop music. It’s the most convenient cliché, the “defense wins championships” of music criticism. Though in the case of Noah Kahan, the credit is warranted. He started previewing the song “Stick Season” on the social media app all the way back in the fall of 2020, nearly two years before it officially came out. In that time the song’s popularity grew as scores of would-be Noah Kahans posted their own covers.

The regional specificity of the track also attracted an audience in the Northeast — the title alludes to a phrase that New Englanders use to describe that bleak period between fall and winter when temperatures drop but it has not yet snowed. (Kahan is like the Whole Foods version of Jonathan Richman.) In the lyrics, Kahan shouts out his home state of Vermont and laments that he can’t travel to alleviate his seasonal depression “because there’s COVID on the planes,” a still-timely reference that felt extra relevant when “Stick Season” first popped up in TikTok feeds.

But the construction of Kahan’s career goes beyond just one app. The rollout for the Stick Season album and the followup reissue has been clever, innovative, and unrelenting. Last summer, one of Kahan’s best songs, the spritely bad boyfriend apologia “Dial Drunk,” received a boost when he recorded a duet version with Post Malone. In the fall, he started releasing duet incarnations of Stick Season tracks with big-name collaborations on a monthly basis. And he chose his partners wisely, switching between established stars (Hozier, Kacey Musgraves, Sam Fender) and young up-and-comers that populate Kahan’s buzzy “popular but not famous” cohort (Lizzy McAlpine, Gracie Abrams).

This strategy has paid off incredibly well in two important ways. One, it has kept Stick Season on the charts. Two, it has made Stick Season (unlike virtually every other album that is released now) feel like a momentous “event” record with serious legs. An album so impactful that even Kacey Musgraves is moved to perform one of its songs. It’s an LP that signifies an “era,” to borrow a phrase used and transformed by one of Kahan’s key influences.

Fourth Attempt: Noah Kahan Is Interesting Because (Some Of) His Songs Are (Pretty) Good

In case it wasn’t obvious from how I have avoided the subject for about 1,200 words I will state it definitively now: I am ambivalent about Noah Kahan’s music. Though I do like exactly four of his songs, which also happen to be four of his most popular. “Stick Season” (more than 487 million streams) typifies Kahan’s talent for setting a scene with some well-chosen details. (The line about an ex’s mom forgetting that he exists is good observational songwriting, particularly if you are a former unremarkable boyfriend.) “Dial Drunk” (155 million streams) demonstrates his seemingly effortless knack for writing anthemic songs that deliver Pavlovian emotional surges with every soaring oh-oh-oh. “Northern Attitude” (55 million streams) is his funniest song. (He appears to blame acting like a jerk on bad weather, which is sort of the opposite of what Shirley Manson does in Garbage’s “Only Happy When It Rains.”) And “Homesick,” my personal Noah Kahan tune (nearly 100 million streams), is the one time he (almost) rocks.

On these songs (as well as the voluminous number of lesser Noah Kahan numbers) he reminds me of a northern Zach Bryan. Both guys present a sensitive but still traditionally masculine image that melds fashionable terminology about trauma and addiction with more old-school ideas about solitary men who stoically nurse wounded feelings about failed relationships and troubled childhoods. Though Kahan, mercifully, isn’t as prone to churning out mid-tempo downers. Rather, he’s more inclined to inspirational maximalism. This starts with his voice, a keening tenor that resembles Robin Pecknold of Fleet Foxes after an extra large cup of Dunkin’ Donuts coffee. Even Kahan’s most introspective and depressive tunes bop along with briskly plucked guitars and banjos as well as hand claps and boot stomps, a formula borrowed from the Mumford wave of jaunty and suspenders-wearing folk-rockers of the early 2010s. (At least Kahan, to his credit, dresses like someone from the current century.)

As for Taylor Swift, Kahan adopted the form of songwriting that she popularized and codified for the present generation of singer-songwriters, from Olivia Rodrigo (a noted Kahan fan) to Conan Gray to the members of Boygenius. It’s a style based in extreme literalism, in which the singer presents the lyrics as straightforward diaristic confessions about romantic misadventures. Language-for-the-sake-of-language songwriting is the antithesis of this approach; the result, if not the intention, is to build a parasocial relationship with an audience that sees themselves (and just as important sees the artist) in the lyrics. Ambiguity, metaphors, or poetic incoherence are unacceptable. These songs have to be explainable or at least “solvable.” Relatability is a requirement. The artist doesn’t have to always “be a good person” in their songs, whatever that means. But they must be self-aware and self-deprecating about their misbehavior. Binge drinking, personal pettiness, romantic volatility — these things need to ultimately signify something noble, a cathartic expression of truth in pursuit of health.

On Stick Season, Kahan writes about sobriety (“Orange Juice”), taking his meds (“Growing Sideways”), and the unsettled state of his parents’ marriage (“All My Love”). It’s impossible to miss what these songs are about when you listen to the record, though Kahan has also spoken with admirable openness about his own mental health struggles. He even started an organization to propagate emotional wellness. These are good and positive lifestyle choices, and I commend him for it. He comes across as a solid guy. But as art, many of Kahan’s songs fall into the “songwriting-as-posting” zone, in which individual lyrics appear to be expressly designed for sharing via tweets and Instagram posts, like a status update set to three chords.

Kahan is undoubtedly good at coming up with a memorable line, like “I’m mean because I grew up in New England” from “Homesick,” which I am sure has enchanted countless self-justifying Massholes in the greater Boston area. What’s less endearing is his overwhelming solipsism. Nothing is more fascinating to Kahan than the minutia of his own screw-ups. Like the other Swift-adjacent artists who work in this vein, his songs start to feel suffocating when you listen to a whole album’s worth of them. I certainly ran out of patience during the annoying (and very Swift-like) “She Calls Me Back,” in which Kahan runs through his inner monologue while pining over yet another girl who got away. “Does it bite at your edges? / Do you lie awake restless? / Why am I so obsessive?” I don’t know but here’s a guess: Because this sort of performative fretfulness pays?

Fifth Attempt: Noah Kahan Is Interesting Because He Is A Human Streaming Algorithm

Of all the interviews Kahan has given during his momentous rise, the one that sticks out most was posted on Grammy.com at the end of 2023. The premise was for Noah to single out the most crucial moments of his career so far. The success of his breakout song “Stick Season” naturally made the cut. Here he is talking about how quickly his audience responded to the track:

A lot of my set at the time was more pop-leaning, and this song is definitely more folk-leaning. I could really see the desire for sing-along folk anthems after that performance. [I remember] talking to my team and being like, “I think this song is gonna be around for a long time.”

Here, again, Kahan displays a Swiftian tendency, though in this instance he echoes her impeccable business sense. I could really see the desire for sing-along folk anthems, he says. And that’s what he delivers, over and over, on Stick Season. Even songs that might have benefitted from a scaled-down approach, like the lilting “Orange Juice,” eventually give way to the hand claps and the ohhhhs. He can’t help himself. It’s what people want. And his team agrees.

Sixth Attempt: Noah Kahan Is Interesting Because Resistance Is Futile

Have you heard of Noah Kahan? You certainly have now. And he might already be your new favorite singer-songwriter or the latest dude you despise above all the other white dudes with guitars. Ten years ago, during the height of Mumford & Sons, I regularly mixed with two camps of people: Music critics who could not stand Mumford & Sons, and “regular people” who would not shut up Mumford & Sons anytime they performed on an awards show. I have had a similar experience with Noah Kahan. My brother-in-law — a man who always seems to know about “huge on Spotify” singer-songwriters before I do — is a casual Busyhead. I’m guessing at least one of your in-laws is one, too. Noah Kahan is a man built for streaming platforms. If a Noah Kahan song comes up on a playlist, it will grab you. That’s what it was built to do.

And there are a lot of other “popular but not famous” guys who are ready to fill the secondary Lumineers/Head And The Heart slots in the long tail of Kahan’s success. People like Warren Zeiders and Briston Maroney are waiting in the wings to serenade us about their hang-ups. This kind of music is back. This kind of music never went away. Get used to it.