Women are not mysteries. That argument has been made dozens of times to many well-meaning men complaining they simply can’t grasp the mechanics of existence when it comes to the fairer sex. They never seem to get it, instead complaining that our minds are enigmas, our emotions uncontrollable, our bodies ticking time bombs in need of more governance. We’re even jokingly told we hail from a different planet, as if our natures are so alien, that they chart separate elliptical paths.

Women are not mysteries, and nor should our bodies be.

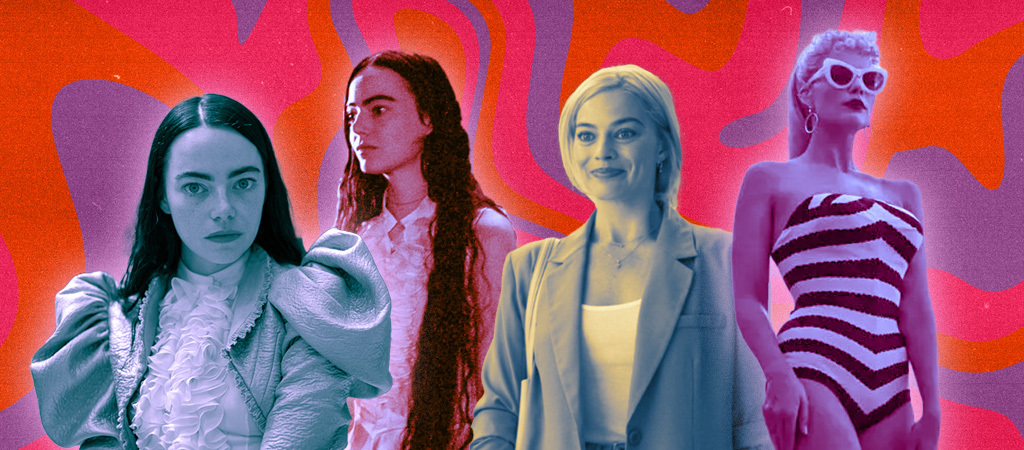

Maybe that’s why films like Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Yorgos Lanthimos’ Poor Things felt so revolutionary, so shocking when audiences saw them last year. One was a fuchsia-soaked existential crisis in commercial doll form, the other a steampunk feminist Frankenstein. But both, oddly enough, gave us a liberating depiction of the female body – its hungers, its flaws, its perfections, its power. In a medium like film, a woman’s body has rarely merited three-dimensional thought. It’s been a tool for pleasure, sure. A battleground, a punching bag, a seductive weapon, a maternal incubator, but rarely has it served as the main character of its own story. And yet, the body is what drives much of the discovery in both Gerwig’s and Lanthimos’ “coming of consciousness” films.

For Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) — a natural-order-flouting experiment conceived by a brilliant, tortured scientist who answers to the name God (Willem Dafoe) – that discovery begins, as Eve’s did, with an apple. With her childlike brain inhabiting the reanimated body of her dead mother, Bella spends the earlier parts of the dark comedy jerking and stumbling through a posh London mansion, breaking dishes, soiling herself, and wobbling her way to adulthood. When she uncovers the bliss of sexual pleasure via a flesh-covered fruit at her creator’s dinner table, she finds happiness. Her body is what informs her of a key aspect of human existence, something that becomes all the more confusing as she’s shamed and restricted from indulging in the masturbatory act again.

When she’s offered freedom by the soft-bellied cad, Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), Bella seizes her chance to question her body further, asking its limits as she “furiously jumps” – a phrase used to convey her naïve understanding of penetrative sex –her way across continents, sampling from an orgasmic buffet of positions and partners, much to the dismay of her original paramour. But Bella’s body doesn’t simply stop once it receives its carnal education. Her insatiable appetite expands, to Portuguese pastries rebelliously stuffed in her yawning mouth, to flailing limbs interpreting the strange, pulse-pounding sounds of a ballroom dance, to the flurry of words in philosophy books, to the social injustices wrought upon those deemed different or less than. In Poor Things, Bella’s body is both a sponge, absorbing the joys and horrors of life, and a tool she uses to dismantle the invisible, patriarchal shackles meant to “protect” and “save” her from her own debased nature.

Gerwig’s treatment of the body is less salacious and more subtle. The concept of death, the idea that the body may one day die, is what sparks Barbie’s (Margot Robbie) transition from blissful ignorance to a sobering reality. When gravity grips her perfectly arched feet, her matriarchal utopia is thrown into chaos. She experiences physical pain, perhaps for the first time, as she tries to contort her disgustingly flat appendages into her beloved heels. She begins finding imperfections in her form – her breath that stinks, her hair that knots, her thighs that carry fat deposits called cellulite. Gerwig uses a glossed-over form of body horror to push Barbie out of her comfort zone, dropping her in Venice Beach in a brightly-colored leotard that pulls the leering, objective focus of men. It’s here – with her body on display, being consumed for other’s entertainment and enjoyment – that Barbie begins to suspect the real world is not a perfect mirror for the safe, nurturing environment she’s cultivated in Barbie Land.

“I feel kind of ill at ease, like I don’t know the word for it but I’m…conscious, but it’s…myself that I’m conscious of,” Barbie innocently tells Ken (Ryan Gosling) to which he enthusiastically replies, “I’m not getting any of that. I feel what can only be described as admired but not ogled. And there’s no undertone of violence.”

“Mine very much has an undertone of violence,” Barbie clarifies.

It’s a darkly comedic moment, one meant to land more with female viewers than anyone else. The threat of bodily harm is one that hounds every woman. It can dictate our daily habits – from how late we stay out at night to what we carry in our bags to who we accept help from. Our bodies are constantly judged – if not by others, then by ourselves. Did I cover up too much? Did I not cover up enough? Did I send some kind of signal? Did I not pay enough attention? Did the way I look, speak, or act somehow invite that dangerous attention? It’s maddeningly unfair, a woman’s reality, which is why it feels so cathartic to laugh at Barbie’s naivete in this scene. Here’s a gorgeous woman learning, for the first time, that her beauty doesn’t just belong to her as her himbo sidekick skates merrily along, completely oblivious and all too happy to reap the rewards of their reversal of circumstance.

That communal relief of being seen is what helps the film’s final scene – Barbie’s first trip to the gynecologist – land so perfectly. Despite being controversial among some swaths of audiences and critics, Barbie’s never more relatable to female viewers than when she excitedly arrives for her appointment, believing it to be a wondrous right of passage. She’ll learn the uncomfortable truth soon enough, but again, it’s the body and how womanhood means constantly learning about it, taking care of it, listening to it, and accepting it, that pushes Barbie to take this next life step.

Connecting with the body is what empowers both Barbie and Bella in their respective journeys. Bella’s stint at a Parisian brothel helps her to understand power dynamics as she fights for her right to say yes and when during her many sexual encounters. She discovers what pleases her, what doesn’t, and most importantly, why that knowledge is so threatening to men like Duncan and her estranged “husband,” a man eager to rob her of bits of her anatomy to better control her. Without a clitoris, without pleasure, perhaps she will shrink herself, but Bella’s body has already realized it’s not simply sex that makes her happy – it’s freedom. To choose, to hunger, to consume, to taste, to feel, to experience. And while her anatomy acts as a key to unlocking the larger world, Barbie’s evolution from artificial to organic teaches her about herself – her desires, her abilities, and her purpose.

In demystifying the female body, Gerwig and Lanthimos buck a troubling cinematic trend – one that’s sterilized some of the messier parts of being human. Movies and TV shows are constantly being criticized for sporting too much sex, superfluous nudity, or for putting bodies on display. Some do so needlessly, warranting that pushback. But if we ignore the body – especially the female body – in stories meant to confront stereotypes and challenge societal conventions, we lose a key element of womanhood. Worse, we relegate the female body to something unknowable, devaluing it, and making it easier to misunderstand, misdiagnose, and misuse.

Both Barbie and Poor Things know that there’s power in the female body. It’s time we own it.