There is good and there is Oscars good. The Substance is GREAT. Like, disown members of your family if they don’t love it great, but writer/director Coralie Fargeat’s utterly fascinating and shocking film is absolutely not going to win any major Oscars.

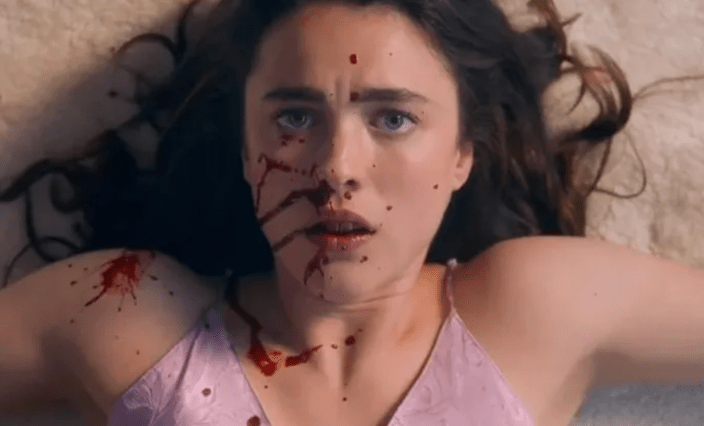

For anyone in need of a refresher, The Substance is about a faded star (Demi Moore as Elisabeth Sparkle) fighting a full-scale war against age-aided irrelevancy. When a mysterious solution is presented, she buys in and unleashes the most monstrous creation imaginable: a vibrant, perfect younger version of herself who isn’t great at sharing (Margaret Qualley as Sue). The film is a penetrating satire about toxic male-gaze-defined beauty standards in Hollywood and youth obsession. It’s also a body horror story that evokes comparisons to the works of Sam Raimi and John Carpenter.

Were it not for that last part, you might think the film would have better odds for gold, but horror almost always has to deal with a respect deficit and the truly berserk back half of the film – a 25-minute blitz of blood and mayhem – puts a definitive end to any Oscar dreams. This fact calls into question (for, perhaps, the one millionth time) the relevance of these awards.

If your celebration of cinematic excellence runs through narrow channels defined by decrepit ideas about what is and isn’t award worthy, you’re not really in the business of celebrating excellence, you’re in the business of jerking off. And that business has a cooling effect on innovation at a time when white noise and focus-group tested templates for success fill the space – a deluge of ephemera or content, nothing classic or worthy of discussion or remembrance.

Fargeat is two full length films into defining a specific style that is allergic to that kind of movie. Instead, she uses shock to say something. In 2017s Revenge, a story about a woman violently assaulted who goes on a rampage in pursuit of justice, the volume of blood turns a house into a slip and slide, and extreme closeups of wounds prove jarring. The film is raw, but the message is crystal clear about the distrubing way women are treated (on screen and off) as disposable sex objects as you root for Matilda Lutz’ Jen to keep fighting and keep surviving, displaying an almost supernatural resilience.

In The Substance, Fargeat deploys some of the same methods – tanker trucks full of blood, slow motion hyper-focus on things like rotting flesh and Dennis Quaid shoving prawns into his maw. But it shifts from a literal desert to a moral one in Hollywood – brighter, bolder, and causative of the psychological torment and physical devastation wrought by the aforementioned unrealistic beauty standards that twist people inside out.

The horror comes from a spine split the length of Demi Moore’s torso (and all that comes next), but also from a scene where Qualley’s character becomes paranoid while exposed during the shooting of a fitness video.

Both actors are so often exposed that they have to deeply trust Fargeat’s vision and methods. Moore is relentless in her portrayal of a character’s descent into madness and rot. Qualley (who we rightly labeled as “our most adventurous young star” recently), like Moore, puts her body on full display, sometimes in scenes that push up to the boundaries of actual objectification, but it’s all in pursuit of the larger point about how the character is viewed.

Men, lacking all awareness of self and surroundings, project their grubby lust onto her without consideration for her wants or needs. Sue is made into a doll, posed and placed where they want her. Elizabeth Sparkle, on the other hand, is 50, and so they look right past and dehumanize her. These sins are all committed by a band of indistinguishable old white dudes led by a lizardly Quaid, who it seemed we had lost to movies about miracles and baseball, but who has just enough twinkle in his eyes to sell the vision of this slovenly monster.

Fargeat is using a broad canvas here, pulling a massive slice of culture under the microscope. And it works so well, grabbing hold of and shocking the audience. Seriously, see it with as many people as you possibly can (as fast as you can as it seems to be falling out of theaters fast). Let the cascade of unusual audience noises – audible cringes, shrieks, wildly inappropriate giggles, and shouts at the screen – enhance the experience.

The Substance is bold and confrontational while also being highly stylized (the sparse packaging of the literal Substance, the Kubrickian hallways, the boldly colored jackets and spandex, UK composer Raffertie’s entrancing and thumping EDM score). It wants to be remembered in such a way that you leave the theater a zealot who is excited to tell people about what you’ve just seen. You want them to see it too so you can talk about it. That buzz is the mark of a truly special film. Hardware or no.

At some point in the process, many specific moments in The Substance could have been sanded down to create a horror story for Oscar voters who seem to only occasionally elevate psychological horror, but who get squeamish when gore and shock enter the chat. Thank goodness and thank Fargeat for being uncompromising. This is a visionary who is exciting for her sensibilities and disregard for our discomfort. If I read people saying she should direct a Marvel movie next, I’m going to put my head through a mirror.

The Substance is a film that wanted to bury a message within the juicy entrails of a sicko symphony, indifferent to if it got the gold star that too many people think represents the only pathway to cinematic immortality. It isn’t, and The Substance‘s run as an influential cult classic is about to prove that.

‘The Substance’ is in theaters now.