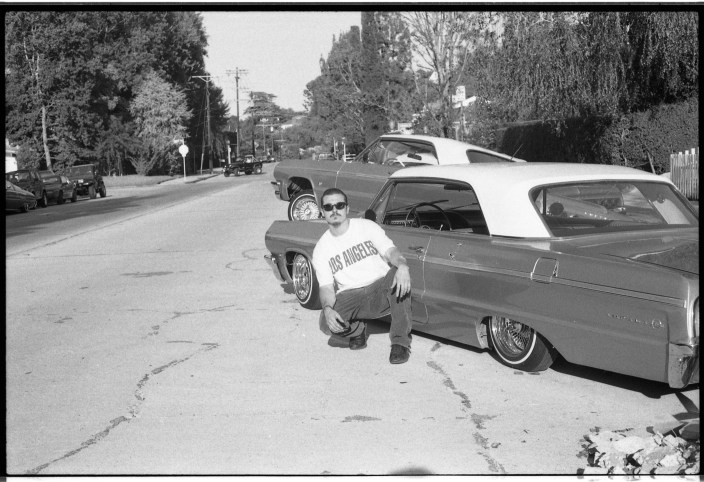

When it comes to Los Angeles, Estevan Oriol has seen it all. The photographer, director, fashion label head, and entrepreneur was there when DIY punk rock and new wave culture spread throughout the southland in the ‘80s. He was there during hip-hop’s rise from a niche hood sub-genre to a global dominating force. He watched the landscape and skyline of Los Angeles grow and transform into what it is today.

Oriol, who has taken many an iconic LA photo (including the best documentation of the LA fingers symbol in our opinion), first got into photography at the urging of his father, who gave him an old camera and told him to document his experiences as a tour manager for ‘90s hip hop groups like House of Pain and Cypress Hill. Oriol hasn’t put his camera down since.

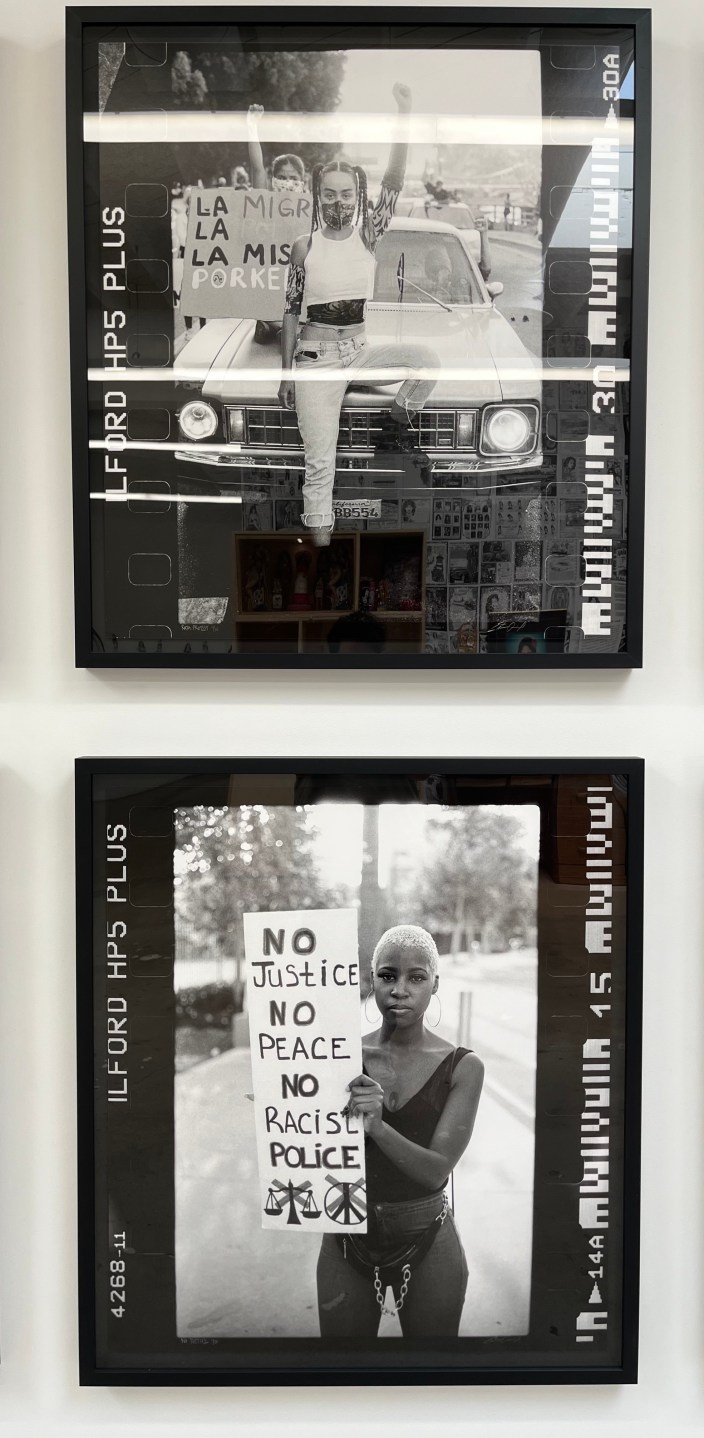

During the George Floyd marches in 2020, Oriol was where he’s always been — in the streets with the people, finger on the pulse, documenting it all with his camera. Even a rubber bullet to the chest during the protests couldn’t dissuade him from telling the story of the streets.

Throughout his career, LA isn’t the only place Oriol has been; he’s established a name for himself that spans countries and cultures, whether that means documenting the burgeoning Japanese low-rider scene, taking portraits of everyone from Al Pacino and Robert De Niro to Kim Kardashian, Chloe Grace Moretz, Eminem, and Snoop Dogg, to working with big brands like Nike and Cadillac. His work has been shown in galleries and institutions worldwide, establishing himself as one of the most influential documentarians of Los Angeles Chicano culture.

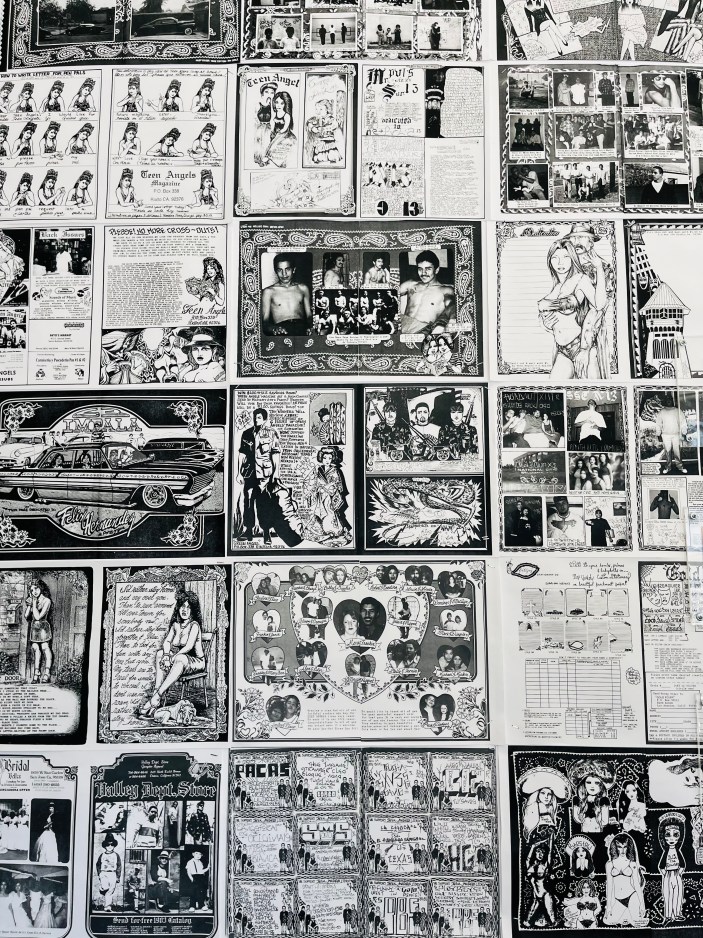

Only one other name comes to mind when I think about influential artists who helped shape and chronicle Chicano culture in LA — Teen Angel. For those not in the know, the late Teen Angel cut his teeth working for Lowrider Magazine before branching off in the early ‘80s to create the eponymous self-published zine Teen Angel’s.

Teen Angel’s was a special magazine for kids and young adults growing up in the barrios of Los Angeles. The magazine featured hand-drawn art, photographs, poems, dedications, and writings that focused on and celebrated Chicano culture. It challenged stereotypes but it also didn’t shy away from the reality of life in the underserved communities in Los Angeles.

It reminds me of one of my favorite Andre 3000 bars from Stankonia’s “Humble Mumble.”

“I met a critic, I made her shit her drawers. She said she thought hip-hop was only about guns and alcohol. I said ‘Oh hell nah,’ but yet it’s that too. You can’t discrimi-hate ‘cause you done read a book or two.”

Teen Angel’s showed that underneath the grime and grit of Los Angeles’ barrios, there was art, love, passion, and a fascinating and uniquely American experience while giving equal space and voice to cholo street culture. It didn’t depict an idealized form of the Chicano experience in America but sought to depict life as it was, warts and all.

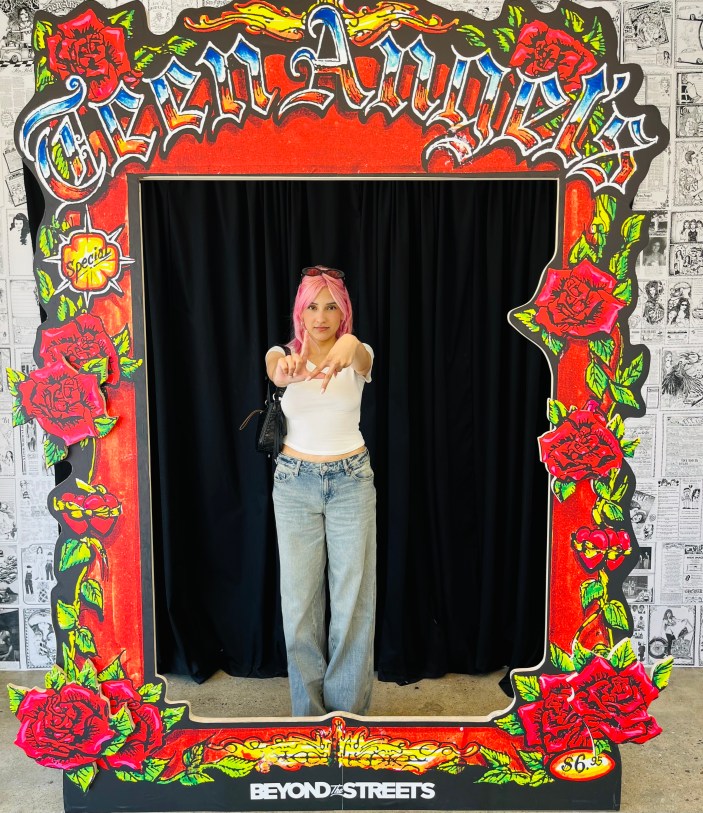

For Oriol’s latest exhibit at LA’s Beyond The Streets Gallery, he has teamed up with the Teen Angel estate for Dedicated To You, an exhibit that celebrates Teen Angel’s Magazine by pairing its style, ethos, and artwork with some of Oriol’s most iconic photographs. We met up with Oriol at the gallery — which is enjoying an extended run until October 27th — to talk about the exhibit, how to keep Chicano culture alive and growing, and got a bit into his clothing brand and future projects.

***

What is the main thing you want this exhibit to convey to people?

This part of LA or this part of the culture in that era [the ’90s]. I just want people to see what it was like, what we were living like and what we were doing, the kind of stuff we were into, the style of everything at that time.

It’s cool that a new generation is trying to emulate it now. Everybody’s bringing back the same style of dress, the low-riding, the cars are still here. We’ve kept the music going. We don’t want to let people forget about that era and this culture.

What was your relationship to Teen Angel, the magazine, early on?

I used to collect it. I loved it and I thought it was cool. It’s like the way people say, “if you know, you know.” That magazine was really that shit. If you know, you know. And 99.99% of the people don’t know.

It was a small thing in our community that we knew about and we collected it. It was only in select liquor stores or newsstands and only in the hood. You couldn’t get it in Beverly Hills. You had to know the stores. It wasn’t a big publication with distribution. His distribution was out of his car in his trunk.

Teen Angel was a real DYI, do it yourself, kind of a guy. Everything was cut and paste. There was no computer, no apps, no nothing. Everything was done by hand.

I can’t even imagine how long it must have taken-

Look at that alone (gesturing to a wall adorned with Teen Angel’s art.) It was so intricate. It’s overwhelming and this is not even a 1% of what this guy did. And as far as the photos go, this is not even 1% of my photos. I was doing this on the daily and still do, I’m not like a pack rat or hoarder of photos, but I just keep shooting every day for no reason. I just love to do it.

I mean, that’s a reason.

Yeah, that is the reason, but there’s no end goal for it.

What do I need more? I don’t need more photos for anything. It’s like millionaires and billionaires, they’re going to die with so much money in their bank that do they need to make any more? No, but they don’t want to stop working. They don’t want to stop the challenge or the game. So it’s like that for me. I don’t want to stop taking photos. I love it and that’s why I do it.

What do you think has been lost with the end of a publication like Teen Angel?

It was one of a kind. It was original and there’ll never be another like it, even if you tried to carry on the legacy or duplicate it. People have told me, “You should try to start it up again.” I could, but I want it to be authentic to what it was and would anybody want it?

People don’t seem to have a need for magazines any more. They just want an Instagram page. You can find one that’s dedicated to this kind of stuff. You don’t have to pay for anything. It doesn’t take up space in your house.

But I thought it’d be a great idea to keep the legacy going and put him in a place like this. He deserves to be in this place or a museum. I am in 28 museums. Smithsonian bought 13 of my pictures two years ago, so I’ve been in museums and will always be a part of museums because I collected my stuff. Teen Angel, all the work that he did and part of the culture he was, he needs to be in a high-end gallery like this.

I just wanted to ask a little bit about how you developed your photography skills. I know you started taking photos when you were the tour manager for House of Pain and Cypress Hill. How would you say your photos have changed from the early ’90s to now?

I don’t think they have. I haven’t changed anything about the way I take them. I haven’t really changed the equipment and I still shoot the same genres. I still shoot hip-hop, street life, low-riding. I would say just the time has changed, the date, but I’m still shooting some of the same people and the same types of people.

I would say that’s pretty well reflected in your photos from the George Floyd marches. If you want to nitpick, you can tell the difference between a photo like that and one of your early photos, but at the same time, there is a timeless quality about both of them that I think is really interesting.

Yeah, I love that. You don’t know when these photos were taken. It could be any time.

What would you say the state of Chicano culture is in 2024? The term “Chicano” is something that I heard a lot growing up in Los Angeles. My mom was very proud to be Chicana. But as I grew up, its a term I heard less and less. Do you think the culture is as vibrant as it was before?

Yeah, it’s just not new. Everything was new back then because there was the 70s movements, the 80s and in the 90s, they were all brand new and now it’s a mixture of all that plus what’s going on now. So you’ve got all kinds of people that argue about what the word “Chicano” means or who’s Chicano, not Chicano and all kinds of stuff.

We want to argue about everything online and who’s right, who’s wrong. I just want to live. I just want to live in peace and positive and non-toxic people and that’s what I see a lot of online, a bunch of toxic activities.

So what does that term, Chicano, mean to you?

To me, it means this era back then. Now people rip the words apart so much and meanings and who’s this and who’s that and where’s your mom from, where did your grandma live? It’s just so much drama. I just like to stay drama-free.

(Pointing out a family walking through the exhibit)

See, it’s cool seeing that lady. She grew up in this time and now she’s showing her kids all this and you see they have a style, the kids, reminiscent of the style back then. They’re trying to keep it alive, which is cool.

That’s exactly what I was going to ask next. How do we preserve that culture?

Like this.

Try and tell the story the way you know it and don’t let somebody else tell it. For example, I want to do a documentary on my dad. I want to do it now while he’s alive, he’s 82. But I want him to tell his story, not us telling it after he’s dead and gone.

I want to give him the opportunity to tell what it was like for him because he was a big part of the Chicano movement in the 80s in San Diego. He was part of a group called the Chicano Federation in Logan Heights and the way he got into taking pictures was he wanted to document the way that industrial people were treating the neighborhoods where our people lived.

There was a lot of pollution, a lot of dangerous shit. Nobody gave a fuck. Kids were walking to school and there’s barbed wire hanging on fences or stuff that could hurt a kid just walking out of school. My dad was an activist and a community leader.

He opened up a bunch of dental and medical clinics free for the people and he started taking photos, documenting all that stuff. A lot of his friends were the ones who did the murals in Chicano Park. I want him to tell that story. And he has the photos to back it up.

Like me, I have photos to tell my stories. I tell people stories and they think I’m bullshitting. They’re like, “Oh, there’s no way.” Six months before this show opened, a young person that is a fan of Teen Angel was telling me about a story of this guy that went to Teen Angels’ house after he died and sho pictures of the way Teen Angels’ house was, exactly the way everything he left it.

I go, “That was me.” And he goes, “Fuck out of here, you’re full of shit.” And they don’t believe it. But I have backup.

You have the photos.

I got the photos. The photos backup all this. I was at Woodstock when there was 500,000 people in the 1994. I was at the riots in ’92 and 2020. I was there when so many things started. Been low riding since I bought my car in ’89. So I’ve seen the nineties, 2000, 2010, 2020. I’m in the culture, I”ve seen punk rock, hip-hop, all that shit from the 80s when that started.

So why are you always putting yourself in these places? Is it just curiosity?

I don’t know why I go. I just go with the flow. Where else should I be? In my house? I want to be where the pulse is. I want to be where the heart is pumping and that’s LA.

As a kid, you want to go to concerts, clubs. I ended up going to punk rock concerts, clubs, all that shit. Ended up working at the clubs, ended up meeting guys that went to the clubs and ended up meeting and working with bands. We toured around the world. Through all that, I met people that were in the low-riding scene and wanted to low-ride since I was a teenager and then ended up getting my own low-rider.

And then I started taking photos after that. Other photographers have shot this culture, but they were coming from the outside, just thinking “Hey, that looks cool. I’m a photographer. I know exactly how to document.”

But I was already in the culture and then I started taking photos. I get mad at myself because I didn’t take enough and I wasn’t a real photographer, I didn’t approach it that way. I could’ve thought like, I’m going to shoot a segment of girl gang members and then guys and I’m going to shoot details of the hairstyles and the kind of shoes they wore and the jewelry they wore. I didn’t think of it like that. I was just like, “Hey homie, that looks cool. Let me get a flick of you in your car that I’ve seen you working on for two years.”

It was just a different approach for me. I got some good shit, but I missed a lot of shit.

How do you feel about Japanese low-rider culture? I know you worked with a lot of Japanese mags back in the day.

I love it. They’re fucking incredible. They’re great. I almost want to say they do shit better, but–

People will come for you.

Yeah, I don’t want everybody to get butt hurt. But the Japanese, fuck, man, they kill it. Food, design, style. They took what we did to the highest level and how are you going to be mad at them for that?

People look at it like, “Oh, they’re taking our shit.” They’re taking our shit and making it look better. What’s wrong with that?

I wanted to talk about your clothing brand, Joker. Tell me a little bit about that.

Well, how it started was that originally me and my partner, Big Lucky, were doing construction and working on this guy’s house in Hollywood Hills and he liked the way we dressed, Dickies, Levi’s, Nike Cortez and stuff.

He liked our whole thing and said “I want to open a store.” So we opened a store called Super Max in 1992, and it was in between Martel and Poinsettia on Melrose. We carried 501s, Dickies, Cortez’s, Chucks, pro club T-shirts, old school clothes, and then we brought in Cypress Hill and House of Pain merch in there.

The owner of that store got cocky and started trying to act crazy with us, treated us like shit because he was the boss. We weren’t going for that. We’re trying to do something cool and he was being a dick. We were like, “fuck him.” So we shut it down and he moved out.

Then we started a clothing company called Not Guilty, and we didn’t know anything about business so we incorporated it and we had this book with a stamp and we thought we were in the business game. I graduated high school with like a 1.8, which was just the highest D you could have, and my friend graduated with that or less. He didn’t give a fuck about school either.

So we didn’t know anything about trademarking, copywriting, incorporating, llc, none of that shit like they should teach you in school. We came out with this incorporation book and we thought we were doing it and ended up getting shut down by this lady that had the trademark worldwide. So we went to her office and we’re like, “Hey, let us do the hip-hop version of Not Guilty and you can do the lame shit that you do.”

We had just been on fucking TV for Woodstock, Be Real was wearing a Not Guilty shirt. But she ended up shutting us down. Then in ’95, me and Lucky had got Everlast from House of Pain to invest and then I stopped working with him and started working with Cypress.

B-roll was like, “Hey, why don’t we start a clothing line and I’ll be the investor.” So we got Joker… Lucky was in prison. When he came out, we had him running Joker.

So me and B-roll were taking care of marketing and all that shit while on tour and blasting it out to the people. Lucky handled the shit back home. But we didn’t realize we were essentially being influencers, doing marketing… but to us we were just like, “Hey homies, let’s just wear the shirts on stage and we’ll give them out to all the homies that are on tour with us.”

That’s how we were thinking. But in the scheme and scale of things, the way businesses work, that’s crazy. That’s what every company wishes for. It was a fucking multi-platinum band wearing the clothes on every single tour and giving it to other bands that they’re on tour with.

So as we were building up Joker, B-roll wanted to use his money toward the music instead. So we paid him back and then I got other investors and that was a shit show, a fucking circus act and ended up getting burned a couple of times and now it’s just me and I’m keeping the legacy going.

With those other investors, the brand had gotten watered down and ran into the ground by people that were only interested in the money. They didn’t care about the integrity of the brand or preserving the culture of it. They’re just like, “fuck it, let’s do it cheaper and make the most money.” And if it’s shit quality, who gives a fuck?

But me, I gave a fuck. I was working with guys in Germany and Japan, they cared about the brand and the integrity and the quality.

But once I had a partner in that deal, he killed himself in a car crash, fell asleep at the wheel and ran and into the back of a semi. But once he was done, the other money people and me were on two different pages. So it took me a while to get it back from them, but once I got it back on my own, now I can do whatever I want.

If I want to make 10 shirts, I can make 10 or 10,000.

If I get a couple of thousand extra bucks and I just want to do a shirt for that, I do that. If somebody wants to do a bigger thing, I’ll do a bigger thing. But now I keep the quality what it’s supposed to be, how we started it.

What would you say the touchstones of Chicano and Chicana fashion are in your opinion? What does the uniform look like?

Right now, it’s all over the place. I’ve seen skinny jeans and guys that used to wear 2XL shirts wearing a small shirt. But me? My clothes haven’t changed since the 90s. These jeans have a 46, 48 waist.

My daughters took me to a store in the mall saying “Hey dad, you need to get with the times you’re stuck in the 90s, you’re wearing 2-3 XL shirts and 46, 48 pants.” I used to wear bigger ones, but I’ve toned it down a little bit now that I’m older.

I went to try on all those clothes and I came out looking like a fucking clown. And I was like, “Okay, I got my Jordans on and my fit, how do I look?” And they go, “Shit.” Even the girl, her job is to sell clothes, it’s the number one store in the mall. She’s like, “Nah, nah.” She goes, “Sir, can I be honest with you? My job is to sell clothes. You look better with what you came in than anything that I could think of putting on you, it ain’t even worth me making the money. You look cool how you are.” Thank you. I got to tell my daughter, “you see?”

Does your daughter have a Chicana influence in her fashion sense, or is it her own thing?

She’s on her own, but she grew up in it, so she gets it, but she also is staying with the times. She’s relevant, current. We always have to learn from the young people, but at the same time, you have to be you, that’s what I try to do.

For my final question, I wanted to ask — I know you make documentaries. This is LA, we’re a movie-making town. Have you ever thought of making a movie? And if you did, what era would it be set in?

I do want to make movies, that’s why I started doing documentaries because I thought if I made a documentary and I directed it, in my mind, I figured taht means I directed a movie so I could direct a TV Show, or a movie or whatever.

But Hollywood, they don’t give a fuck what you’ve done before. If I’ve done two number one documentaries, they’re like, “Oh, that’s cool. You did documentary, but you’ve never done TV before or you’ve never done a feature, so we don’t know if you could do that or not.”

What are you fucking talking about? How can that not be you watch it the same? As a person, I go and I sit down and I watch what, and I’m looking at the cameras and the color and the style, the way it’s edited. I’m listening what the people are saying and the music that was chosen. But to them, it’s like a documentary is a documentary, movie is a movie and TV’s TV.

I get that now, but it doesn’t mean that I can’t do it because those are different things. It’s just like acting. Could you do a comedic movie? Once you did a comedy movie, would you be able to do a drama, a thriller, a horror, or a romantic movie?

That’s how they think. To me, I think if you can act, you can act. If you can direct, you can direct.

But I do have ideas for movies and definitely want to do one. And I’ve been pitching movie ideas for about 20 years. So like everybody else in LA or Hollywood, I’m waiting for my big break.