As a dedicated Wilco fan, I have watched I Am Trying To Break Your Heart at least eight times. And that apparently is enough times to actually get sucked into I Am Trying To Break Your Heart. At least that’s how I felt 11 years ago when I had the opportunity to visit the Wilco Loft.

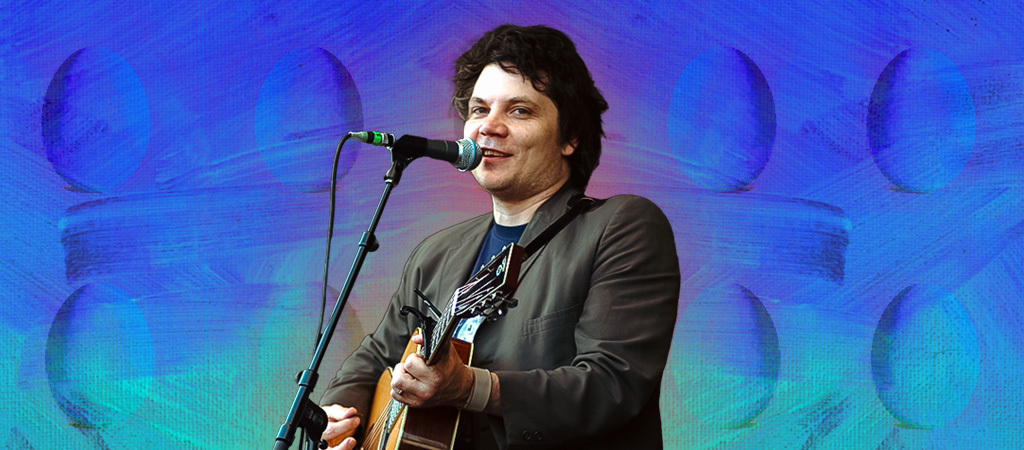

If you love the band, you know about the Wilco Loft. It’s the space on Chicago’s north side where Wilco plays, records, stores about a million guitars, gets filmed for classic rock documentaries, and does all the other Wilco things. I was there to interview Jeff Tweedy about his side project band Tweedy with his son Spencer. It was the second time (out of four) that I spoke with Jeff, and it was the instance where he seemed the least guarded and most vulnerable. (His wife Sue had recently been diagnosed with cancer, and he was understandably emotional about it.)

At some point during our nearly three-hour conversation, I pivoted from the subject at hand to ask about my favorite Wilco record — possibly the least guarded and most vulnerable LP of Jeff’s career — A Ghost Is Born. I did this under the guise of commenting on the album’s 10th anniversary, but honestly I would have used any excuse (the existence of ghosts, the difficulty of child birth, etc.) to bring up A Ghost Is Born. The record means a lot to me.

I shared my own theory about Wilco’s career — which happens to be an opinion shared by many other Wilco fans — that posited A Ghost Is Born as a point of demarcation. Pre-A Ghost Is Born, Jeff Tweedy’s songwriting is rooted in his persistent unhappiness, I argued to the man himself. Post-A Ghost Is Born, there is more clarity and comfort on Wilco albums, which presumably also derives from his personal life.

Now, I didn’t fully grasp this in the moment, but there’s an implication here that must have been offensive to Tweedy on some level. And that is the suggestion that his personal unhappiness made those pre-A Ghost Is Born records “better.” I didn’t mean it that way, exactly, but that was the undeniable point at the root of my cute little critical theory. After all, the album I said I loved the most was the one he made while in the most harrowing throes of addiction, when he was struggling to manage his chemical intake so he could remain sentient in the studio while also singing and playing through mind-crushing migraines.

Jeff Tweedy, to his credit, did not laugh at me or escort me the hell out of his musical clubhouse. Instead, he answered me thoughtfully. “The way I see it is that I was always pretty comfortable with being vulnerable, but not particularly confident. I feel like I’m a lot more confident, but I still embrace the fact that I am pretty vulnerable, if that makes any sense. I don’t have to be somebody else. I don’t have to be as good as somebody else, I just have to keep making stuff that I am excited by. That is one of the only things I have had control over. I am more aware of it — I am more aware of the things that I have control over.”

While I didn’t put it in these exact terms, I was basically applying the “tortured artist” mythology to Tweedy’s work. And that’s the very mythos that Tweedy has for years tried to dispel. He has done this repeatedly in interviews. And he wrote about it in his 2018 memoir, Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back). As he told a reporter the following year, “I don’t just think it’s unhelpful, I think it’s harmful and dangerous for people to believe it. Suffering obviously doesn’t create anything other than misery. There would be a whole lot more art in the world if it was only the product of suffering – I think artists create in spite of suffering, like anybody else.”

This is personal for Tweedy. If you care about Americana-adjacent indie rock, he is one of the foremost examples of the “tortured artist” archetype, especially since he was able to survive said torture and persevere for decades as a healthier and happier person. But what to make of A Ghost Is Born? Why am I attracted to this record? Do l like it for the wrong reasons? Do I misunderstand something I profess to love? If so, what am I missing?

I’ve been thinking about these questions lately, and this time I actually have a good excuse: A massive 10-disc deluxe edition of A Ghost Is Born drops on Friday. It includes outtakes, a concert album from 2004, and several very long jams spread out nearly half of the box set. It’s as fascinating, brutal, moving, thrilling, and challenging as the proper record. It’s given me more of A Ghost Is Born to love, which I appreciate. But more important, it gives a fuller and more accurate picture of Jeff Tweedy’s “tortured artist” masterpiece, and in the process rebukes the “tortured artist” part of that equation.

To be clear: I don’t just love A Ghost Is Born for the behind-the-scenes pathos. When I wrote about the record this summer for its 20th anniversary, I noted that Wilco (like many of my favorite bands) has an “art gallery” side and a “county fair” side. Meaning that they sometimes make difficult and esoteric “art” music, and sometimes they make catchy and strummy “fun” music. And then there’s A Ghost Is Born, where they manage to do both things simultaneously. “Handshake Drugs” depicts the mindset of an addict slowly losing his grip amid a wave of skronky guitars that at song’s end devolve into anxious waves of wiry noise. It also makes you want to sing-along with your arms in the air on a humid July evening. These qualities are not in conflict. They perfectly complement one another. That’s what I love about it.

My friend and fellow Wilco fan Ryley Walker has a different term for it: simple man’s progressive rock. What Ryley meant is that this is music with adventurous artistic aspirations that’s grounded in workaday Midwesterness. (He was referring to the self-titled Loose Fur album but the term obviously fits A Ghost Is Born, a close cousin to that record.) For anyone whose musical sweet spot resides between crunchy Grateful Dead jams and foundational underground guitar bands like Sonic Youth and Television, A Ghost Is Born is a core touchstone of modern American music, a record that connects many dots that previously seemed incompatible.

It was also made by a man whose life was falling apart. And that’s not just mythology — it’s also pertinent to the sound and character of the record. As Tweedy discusses in his memoir as well as the liner notes of the deluxe edition, A Ghost Is Born was originally conceived as a concept record about Noah’s Ark (hence all the songs about bees and spiders and hummingbirds) that he hoped might explain his life to his kids once he was gone.

“I thought I was going to die,” he writes in his book. “Every song we recorded seemed likely to be my last. Every note felt final.”

The most obvious musical manifestation of Tweedy’s condition is “Less Than You Think,” the 15-minute penultimate track made up mostly of electronic drone and mechanical noises. It was so extreme that even the album’s co-producer, the experimental music godhead Jim O’Rourke, didn’t think it should be on the album. But you can also hear it in the screaming guitar solos that Tweedy plays all over the record, particularly the surly bolt of six-string lightning surging through “At Least That’s What You Said” and the panic attack-inducing feedback that swallows “Muzzle Of Bees.” And then there’s “Spiders,” which Tweedy claims was simplified to include fewer chord changes because “my ability to remain upright” was compromised during recording. “This allowed me to just recite the lyrics and punctuate them with guitar skronks and scribbles to get through the song without having to concentrate past my headache too much.”

Jeff Tweedy doesn’t like “tortured artist” mythology. But he was, genuinely, a tortured artist when he made A Ghost Is Born. But is that what makes A Ghost Is Born great? After immersing myself the deluxe edition, my feelings on this subject have evolved.

When I wrote about A Ghost Is Born last June, I argued that it was “a quasi-solo record” for Tweedy. “Not only does the narcotized vibe of the lyrics and music feel extra-specific to Tweedy’s headspace, but Tweedy’s voice and guitar playing are even more dominant than usual,” I wrote. There’s some truth scattered in that sentence, but I now believe the overall sentiment is incorrect. A Ghost Is Born is not a solo record, quasi or otherwise. It’s yet another example of Wilco working together as an excellent band, even if this particular version of Wilco was short-lived.

When most people think about the aughts incarnation of Wilco, they typically envision the transition from the Jay Bennett-era Wilco seen in I Am Trying To Break Your Heart to the current lineup with Nels Cline and Pat Sansone. But there’s a missing link in that chain that’s preserved on A Ghost Is Born, with Tweedy and stalwart bassist John Stirratt joined by recent addition Glenn Kotche on drums plus multi-instrumentalist Leroy Bach and keyboardist Mikael Jorgensen.

Similar to the landmark Yankee Hotel Foxtrot box set, the outtakes discs on the expanded A Ghost Is Born demonstrate how skilled these musicians were at taking Tweedy’s songs and reshaping them a million different ways. Familiar favorites like “Hummingbird” and “Muzzle Of Bees” are variously presented as mentally unwell psych-pop, spooky country, and Byrds-style folk rock. Obsessive fans will delight in tracing the evolution of these songs, but it’s amazing how enjoyable these alternate roads not taken are in their own right.

The most polarizing part of the box set will surely be the eight massive jams spread out over four discs. Dubbed “Fundamentals,” these meandering tracks typically last about a half hour and make “Less Than You Think” seem like a punchy toe-tapper. As veteran music journalist Bob Mehr writes in the liners, these excursions would often unfold with Tweedy on the studio floor with a notebook of lyrics and an acoustic guitar and the rest of the band in the control room extemporaneously responding to what he was doing, without Tweedy being able to hear them. For Tweedy, this was a way to discover the best stuff in his pile of material. On the box set, you occasionally hear songs emerge from the morass of whirs and ambient noise, like the fan favorite “Bob Dylan’s Beard” and “Impossible Germany,” which ended up on the next Wilco record, 2007’s Sky Blue Sky.

If that sounds self-indulgent, Tweedy doesn’t disagree. “I felt encouraged and emboldened by the whole saga of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot to give myself permission to be as esoteric and as pretentious as I wanted to be,” he says in the liners. It also speaks to the willingness of his collaborators to follow his lead, while at the same time supporting and even protecting him during one of his lowest periods.

That is my takeaway from this version of A Ghost Is Born: The rest of Wilco stepped up to rescue the record from an otherwise certain oblivion. The box set underscores each man’s vital contributions — the rollicking piano lick that opens “Hell Is Chrome” pitched in by Jorgenson, the songwriting contributions made to “Wishful Thinking” by Kotche, some of the best basslines ever on a Wilco record by Stirratt, and the myriad instances of low-key instrumental genius from Bach. This was a great band that produced a classic in spite of the hardships, not because of them.