We probably wouldn’t have The Beatles without Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and Elvis Presley. And we wouldn’t have rock and roll as we know it without The Beatles. If you agree with the school of thought that we build off the accomplishments of our predecessors, then Cecelia Payne is as rock and roll as they come.

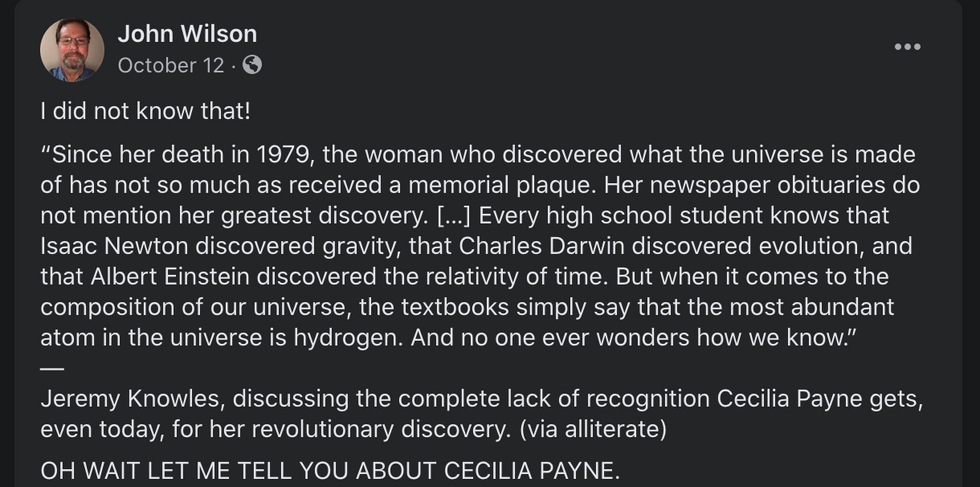

In a Facebook post making the rounds again after the original went viral two years ago, Cecelia Payne is once again having a light shined on her accomplishments. And yet, it still doesn’t seem close to what she deserves.

Born in 1900 in Wendover, England, Cecelia was always fascinated by the stars. According to Harvard Magazine, when in high school she actually approached a local bookbinder in London to put a fake cover that read “Holy Bible” on the book she was supposed to be studying so she could pursue her true passion, which was science. Her silent defiance would eventually get her kicked out of school. After being accepted at the St. Paul School for Girls, she recalls walking through the doors and thinking to herself “I shall never be lonely again. Now I can think about science!” In 1919 she was awarded a scholarship to Cambridge University, which had only recently started to accept women. And while they accepted women, they were a far cry from taking them seriously in the field Cecelia uncontrollably passionate about.

One night, after hearing Arthur Eddington, head of the Cambridge Observatory, give a lecture regarding Einstein’s theory of relativity, Payne raced back to her dorm. She thought, “For three nights, I think, I did not sleep. My world had been so shaken that I experienced something like a nervous breakdown.” And if nervous breakdowns get you into Harvard, then we should all start taking crazy pills, because that is where she would continue her studies.

During her tenure at Harvard, astronomers were trying to answer the riddle that had evaded them and everyone before them: what are stars made of? As they were staring at the stars, befuddled as they looked through their high tech telescopes, Cecelia Payne figured it out. Using a jeweler’s loupe.

What she discovered was that hydrogen was a million times more present in the universe than anyone had realized. When she presented her thesis, the famous Russian-American astronomer Otto Struve called it “the most brilliant PhD thesis ever written in astronomy.” Henry Norris Russell, dean of American astronomers and head of the Princeton Observatory did not agree.

In response to Payne’s book Stellar Atmospheres, Russell called her hypotheses “clearly impossible” and that her results were “almost certainly not real.” Four years later, after using his own methods, Russell came to the same conclusion as Payne’s original idea. He then took the credit giving her an unceremonious honorable mention. Heaven forbid he said, “She was right and I was wrong.” It is kind of like reading someone’s book idea and saying there is no way that would work, and then coming up with that same book idea four years later and calling it brilliant.

Cecelia Payne, you were way ahead of your time. You are the Nina Simone of astronomy.