It’s been a weird year. I know we say that a lot, but it bears repeating. The weirdness of this year is impossible to ignore when attempting to choose your favorite movies. A handful of movies came out in theaters like normal at the beginning of the year, mostly in the January/February months that are the traditional studio dumping ground for their schlockiest schlock. After that, everything got either delayed indefinitely or delayed and then released online.

Except for Tenet, of course. Christopher Nolan is a strict theatricalist, and so Tenet opened in theaters, as if Christopher Nolan willing things to become normal would make it so. Hardly anyone saw it until months later, myself included, and when I finally saw it in an empty theater during the brief window when theaters were allowed to open, it ended up being the most incomprehensible nonsensical big budget blockbuster I’ve ever seen. I would’ve loved to see the conversation surrounding Tenet if everyone had seen it around the same time.

The reverse has basically happened with Wonder Woman 1984. Normally, different critics groups see the superhero movie in successive waves, and then the fan reactions gradually roll in from different times and places, and the conversation plays out predictably. This time around, Wonder Woman 1984 went online the same week as the first reviews hit and it seemed like half the country watched it at the same time. As a critic, it was rare to instantly have that big of an audience for all the jokes I wanted to make. Which is, ultimately, something I care much more about than whether you believe in my “rare expertise” as a movie-enjoyer.

Those are two specific examples, but in general, the salient factor this year was that it was impossible to tell which movie was the “important” one in a given week. Usually there are two or three wide releases in theaters and two or three more limited ones or simultaneous limited/VOD releases. This year, it seemed like every week brought with it 5-10 new movies, all online, and it was hard to tell which ones were someone’s labor of love and which were some megarich failson’s glorified tax shelter.

As much as I find Christopher Nolan’s hard line theatrical-or-nothing stance both obnoxious and over-precious, I do think there is something to the theater-going experience that you can’t quite replicate at home (my pandemic solution would be to close the theaters, but subsidize them enough that they can eventually reopen). It’s not so much the size of the screen or the quality of the sound (though there is also that), it’s more that the theater-going experience still requires a different level of attention span. Your phone is stashed away (unless you’re an asshole), no one is dropping off packages at the door, your dog isn’t rolling around on your lap looking for scratchies, and rewinding is out of the question. Ironically, going to see a movie in a room full of people is still the purest way to create the most direct relationship between you and the movie. As a filmmaker, how could you not want your film to be seen that way?

It’s probably no coincidence that the top two movies on this list were movies I saw in a theater. Even beyond just being able to pay closer attention to them, seeing a movie in a theater cements the viewing in your mind as an experience, rather than just a mundane thing you do at the end of the day before bed. When I write up my end-of-the-year lists, I don’t just tally up my initial rating. “Memorability” is a key part of the equation. Thus movies I actually saw in a theater have a distinct advantage. As do movies I didn’t see as part of my end-of-the-year rush to catch up. Those always have the distinct disadvantage of reminding me of homework — things I have to do because someone else said they were important. That’s tough, a less “important” movie is always more fun. That being said, every once in a while, we do get a streaming release

that takes a few sittings to digest and/or a few watches to appreciate, where streaming-first is actually an asset.

On that note, there were a lot of critically-acclaimed “important” movies this year that to me just didn’t seem that good. It’s always nice when a movie I love also lines up with my politics, and I do find it slightly harder to love good movies with terrible politics, but good art and good politics are not automatically synonymous, or vice versa. It does tend to be easier to criticize a movie with bad politics and harder to criticize one with good politics — hence the existence of all those awards movies we secretly hate. That’s true to some extent every year, but 2020’s overheated political climate, mixed with a rise in displays of feigned corporate accountability and a relative dearth of options, not to mention the ever-more precarious career options for most professional critics, has seemed to exacerbate the situation. Or, you know, to each their own and what not.

Phew. Now that we’ve outlined my seven hundred words of meticulous caveats, we can get to my actual list. Art is subjective and blah blah blah, but suffice it say, if you think any of these are wrong, it’s probably only because you’re a big, dumb baby. Agree to disagree.

10. (Tie) Extraction / Borat 2

Extraction, a Netflix release starring Chris Hemsworth, is a fairly straightforward action movie, and well done. The action sequences were some of the best executed I’ve seen in a long time, and that includes the John Wick movies. The best action scenes aren’t just about how tough the hero is or how badly the bad guys get beaten. They should have rhythm and a sense of humor. A good stunt is like a good joke, or a good magic trick. No matter how short or simple it is, the best ones usually have a beginning, middle, and an end, and maybe a twist. They rely on novelty and surprise and play on your expectations.

Extraction, directed by stunt coordinator Sam Hargave, did a wonderful job focusing on the execution of the action. In one scene, Chris Hemsworth’s character leg kicks one bad guy practically in half, choke-slams another into an end-over-end roll, kills a third with a coffee mug to the throat, and nearly decapitates a fourth with a table’s edge. It has suspense, surprise, slapstick, shock — it’s an entire story in miniature. That‘s how you do a stunt. Meanwhile the camera functioned like an effective referee — good enough that you didn’t much think about it. I’m sure the movie also had a plot, but who really cares?

Borat Subsequent Moviefilm (original review)

There was a lot working against Sacha Baron Cohen in this 14-years-later sequel, starting with the fact that Borat is mostly too famous to do stunts in character as “Borat” anymore. In his place we had Cohen double disguised as Borat in a series of second disguises, including my personal favorite, a singer named “Country Steve” with a string of onions around his neck. Meanwhile, Borat’s daughter, played by Maria Bakalova, someone most of us had never seen before, did much of the heavy lifting. I don’t know if it’s entirely an actor‘s skill that made Bakalova so great, as Borat stunts seem to involve equal parts clowning, improv, and ambush journalism, but Bakalova was shockingly good. It seems like I’m not the only one saying she should be in the awards conversation, which is nice. Though it does also raise the question: shouldn’t Sacha Baron Cohen get awards consideration for doing what he does all these years? I don’t know that Borat movies are necessarily a triumph of acting, per se, but I do know that Sacha Cohen is about the only guy in the world who can do it.

Sure, Borat’s brand of cringe isn’t for everyone, and even as a Borat fanatic, Borat 2 probably isn’t the high-water mark of Borat. But it is still endlessly compelling — spontaneous and surreal in ways few things are, and full of unforgettable moments. A rightwing rally emcee breathlessly running backstage to ask a guy in an obvious fatsuit and dutchboy wig “are you Country Steve?!” is one of those perfectly idiotic moments that will be forever seared into my brain. God bless Borat, God bless America.

9. The Devil All The Time (original review)

Admittedly, you may need a slightly wicked sense of humor to appreciate this one. Sure, on the face of it, The Devil All The Time is an unrelentingly grim tale of violence, dysfunction, murder, and mayhem. It’s also, at least to me, darkly comedic. Terrible things happen, but always with a punchline. It’s as unsentimental about its characters as George RR Martin and as “sensational” as it is, something about it just has the whiff of authenticity. Directed by Antonio Campos, The Devil All The Time was adapted from a novel by Donald Ray Pollock, a guy who worked in a paper mill in Meade, Ohio (where the story is partially set) and didn’t publish his first work until he was 53. The film, starring a geographically eclectic cast of young stars including Robert Pattinson as a horny preacher (nothing against R-Pattz, but I don’t really understand why he gets so much acclaim when the rest of this cast was arguably even better) is partly notable for doing things other movies have attempted, only much better.

The Devil All The Time includes basically the same scene as this year’s higher-profile Appalachian Netflix release, Hillbilly Elegy, both illustrating the adage “never start a fight, but finish one.” Only The Devil All The Time’s version is intense, disturbed, and actually has a point. In a lot of ways, The Devil All The Time feels like the movie Three Billboards was trying to be, just not as self-regarding or reductive. But sure, probably too bleak and morally ambiguous to hear much about it during awards season, which is a shame.

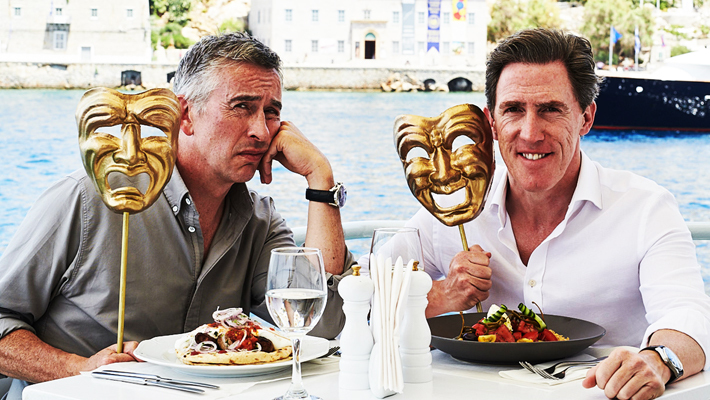

8. The Trip To Greece (original review)

Few movies are as well-suited to streaming as The Trip series. Which is probably because they’re not really movies at all, but British TV shows recut into movies for their American release. Someday we’ll work it out so that Americans can watch British shows without pirated DVDs or VPNs. But for now at least we have The Trips, in which Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon travel to exotic locales doing impressions at each other over fine food. It’s a testament to these guys that many Americans have come to enjoy these movies despite not at all understanding the origins of the celebrity that underpins the whole endeavor. Rob who?

The Trip To Greece, which is actually the fourth installment of The Trip series (The Trip, The Trip To Italy, The Trip To Spain), is a little more melancholy than its predecessors, but also joyful, and without losing the low-stakes charm that makes them so appealing. The Trip movies almost make me wish I was British, just so I would understand all of the references. Almost.

7. Mank (review)

Mank led to one of my most memorable emails from a reader this year, which I shall now share (in slightly edited form):

“Are regular people supposed to watch this movie? Netflix gives its artists total freedom, and I want to think that’s a good thing, but a lot of these movies — I also saw Charlie Kaufman’s movie on Netflix, and that stunk — and Mank didn’t stink, but I just don’t understand how the average person is supposed to watch this movie and get any enjoyment out of it. I just wonder if Netflix is making a case for some of these big studio dinks to come in and commercialize these movies a little bit.”

Oddly, it’s possible for me to agree with this emailer’s sentiment almost completely and still love Mank. It took me a few sittings to finish Mank and some additional context to entirely appreciate it (as I pointed out, 1999’s RKO 281 makes an ideal double feature, provided you can actually find a copy somewhere), but once I did, there’s a lot to love. Mank tells the story of Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz’s friendship with William Randolph Hearst, disillusionment over the 1934 California gubernatorial race, and his eventual crowning achievement with a brutal portrait of his ex-friend in Kane. It’s a little arcane, but that 1934 governor’s race is worth remembering — arguably the first time Hollywood used its might to affect politics, the supposedly-liberal libertines snuffing out an insurgent socialist in Upton Sinclair. It’s a memorable portrait of that time, with great performances from Amanda Seyfried and Charles Dance.

That being said… did David Fincher have to do it as such a stylistic homage to Citizen Kane? The black and white, the heavy shadows, the echo effect on all the dialogue… between that and Gary Oldman playing a navel-gazing alcoholic in the first batch of scenes, even I had to battle the urge to shut it off and do something else for the first 15 or minutes. Ultimately I’m glad I didn’t and was eventually rewarded, but I’m not sure it had to be that way.

6. The Invisible Man (original review)

Yes, I wish this one had had a slightly different ending, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t something special.

Is Leigh Whannell the best pulp director working? Whereas most directors as good as Whannell want to make us think, Leigh Whannell is content to merely make us shit our pants. In Whannell’s The Invisible Man, the umpteenth Hollywood take on the Invisible Man, the title character is, just as in Paul Verhoeven’s Hollow Man (2000), a villain rather than a hero. But whereas the central question posed in Hollow Man was “what would you do if you didn’t have to look yourself in the mirror every morning?” The Invisible Man asks “what would your psychotic ex do if he didn’t have to look himself in the face every morning?”

Elisabeth Moss plays the tormented heroine, turning in yet another nearly perfect awards-worthy performance in what may be the ultimate gaslighting thriller. In fact, just as the term “gaslighting” itself was becoming so overused as to be almost meaningless, Invisible Man and Elisabeth Moss came along and made it terrifying again. The Invisible Man is one of those horror movies so well done that the main consideration in recommending it is whether it’s too intense.

5. Babyteeth (original review)

Babyteeth is an offbeat Aussie drama, anchored by the great Ben Mendolsohn and Essie Davis from The Babadook, that seems to have flown way under most people’s radar. It’s a shame, because it’s one of the year’s great ensembles, in a film that’s both indelible and exquisitely painful. Mendelsohn and David play the parents of a teen daughter, who’s dealing with some problems way above her maturity grade, and who eventually gets involved with Moses, a sort of feral child/drug addict who is equal parts What About Bob and every parent’s nightmare. Or, to use a more obscure analogy, he’s a lot like Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s character in Hesher, the wild card that shakes up a family in the midst of a tragedy. This one is now available on Hulu so you have no excuse.

4. Portrait Of A Lady On Fire (review)

I’m an impatient person by nature, but that doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate a patient movie. The beauty of Portrait Of A Lady On Fire, from French director Céline Sciamma, is that it actually rewards your patience. A story about a painter sent to paint a portrait of a countess’s daughter in 1700s Brittany (fun fact, the countess is played by Ramada from Hot Shots), with whom she eventually falls in love, it is in many ways the female analog to Call Me By Your Name. As I wrote in my initial review, “Obviously, attempting to know your crush’s features by heart in order to paint her from memory is a much subtler form of seduction than, say, f*cking a peach with a hole in it while thinking of Armie Hammer.”

And yet… it’s somehow also more satisfying? Amor fou this ain’t. It’s more like the love equivalent of day by day, little by little convincing a chipmunk to eventually eat out of your hand — the love shared by the easily spooked. It’s also immensely gratifying when it finally happens, a doomed, self-abnegating kind of viewing experience. I can’t remember the last time a movie was this patient in revealing its charms; reeling you in so slowly and with such a gentle hook that one minute you’re swimming around and the next you find yourself flopping around in the bottom of the boat. Check it out the next time you’re feeling unhurried and slightly morose. This one is also available on Hulu.

3. Dick Johnson Is Dead

One of the difficulties of putting together these lists is knowing what to do with the docs. There were so many good ones this year — 537 Votes, The Swamp, Boys State, The Dissident — but I suppose I limited my documentary inclusions to the one that felt like an achievement in creative storytelling as much as a straightforward reporting (not that movies shouldn’t be celebrated for that!).

In Dick Johnson Is Dead, which is destined to be forever confused with another favorite of mine, The Death Of Dick Long (I guess I just love dead Dicks), documentary filmmaker Kirsten Johnson deals with her father’s recent dementia diagnosis and impending mortality by having him play himself in a series of death scenarios that she has imagined for him. The movie jumps between those scenes that they’ve filmed, and the documentary version of those scenes as they’re being filmed.

Movies about death and dementia are often too sad or painful to sit through, but Johnson’s method of turning it all into an extended flight of fancy, living in the grey area between fiction, fact, and possibility, actually gives us a language to discuss those awful things in ways that aren’t depressing. It ends up being not only not sad, but weirdly life-affirming. At times even hilarious, like during a staged funeral for Dick Johnson, during which one of his genuinely grief-stricken friends plays for him what can only be described as a “mournful kazoo dirge.” It helps that Dick Johnson himself is a lovable old charmer. It’s a must-watch, especially in a year where everyone has had to contemplate mortality. Long live Dick Johnson!

2. Palm Springs (original review)

Speaking of people who should be in the awards conversation, Cristin Milioti’s delicate dance of sardonic wit and genuine vulnerability as Andy Samberg’s love-interest-sucked-into-a-time-loop in Palm Springs stands out as one of the year’s MVPs. Of course, as is true for most of the movies on this list, the entire cast of Palm Springs is delightful, from JK Simmons’ intensity to Andy Samberg’s goofball charm, not to mention a cameo by Conner O’Malley, a sight gag for anyone aware of his other personae.

Palm Springs is, obviously, something of a riff on Groundhog Day, which is unimpeachable in its own right. But to call it derivative is missing the point; it hijacks an existing premise to comment on something new. Whereas Groundhog Day is mostly a light rom-com, Palm Springs is an introspective meditation on relationships that feels closer to Eternal Sunshine than When Harry Met Sally (and it’s still pretty funny).

Palm Springs is a movie about… being able to find happiness in what can feel like meaningless, repetitive drudgery; about the abiding loneliness of existence, and about ultimately being stuck with yourself. With not just your own tendencies but with the ever-present weight of your history. How much of what you do is because it makes you happy and how much is you building towards some future goal? How much do those future goals really matter, aren’t they ultimately meaningless? What if you stripped away all possibility of any future goal or the normal external benchmarks of personal growth? Would that make your life more meaningful, or less? It’s a movie that stares into the abyss and finds… well, love and humor, mostly. What would we do without The Lonely Island boys?

1. Sylvie’s Love (original review)

For cinematic comfort food you can’t do much better than Sylvie’s Love, a sweeping romance set in 50s-60s Harlem. It’s a film in which the soundtrack, story, and glowing cinematography are all inseparable, and somehow more than the sum of their individual parts. It’s almost an arthouse jukebox musical, with some of the most insanely charming performances ever committed to film and a montage set to Sam Cooke that truly wrecked me. Also, if you liked Lance Reddick in his intense performances as Daniels in The Wire or the boss on Corporate, you’ll love him as a gregarious jazz dad in Sylvie’s Love. Seriously, Lance Reddick should play nice guys more often.

One of the interesting things about Sylvie’s Love is that it almost didn’t get made. Though it’s a simple and seemingly classic story, as star Nnamdi Asomugha and writer/director Eugene Ashe told me, studios and financiers didn’t have a model for a black love story that wasn’t really a rom-com and isn’t really about Civil Rights. Thus they were hesitant to finance it. So what is it? As Ashe told the New York Times, he was partly inspired by the period photography of Gordon Parks, including his 1956 photograph, Department Store, Mobile, Alabama.”

“When I first met with Tessa,” he said, “I had that picture on my iPad and showed it to her. It had the whole picture with the colored entrance sign. I said to her, ‘We’ve seen this movie. I want to make this movie,’ and I zoomed in to where the sign was gone and it only focused on the woman and her child. We talked about making a movie that wasn’t framed through our adversity, but that focused on our humanity.”

Even in an industry that claims to be all about representation these days, it seems as if there’s still only room for certain kinds of representation. Sylvie’s Love didn’t want to depict black people defined by adversity, and so people didn’t know what to do with it. Even though there’s already been a Brooklyn, even though there’s already been a La La Land, there hadn’t been that story with black people. Somehow the moneyed interests still saw them as inherently different. Luckily, Ashe found Asomugha, and they made it happen, and Amazon eventually released it.

The beauty of Sylvie’s Love is that even though it’s kind of like Brooklyn, it isn’t derivative in any way, and even though it’s not strictly about the civil rights movement, the doesn’t exactly pretend it didn’t exist either. Instead, it’s a movie that’s the best thing a movie can be — true to itself and its own specific vision. It’s a testament to the filmmaking that a romance with a bicycle-built-for-two scene can somehow come off not saccharine.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.