“The Bum Out Front,” the 14th episode of the CBS series Frank’s Place opens with a character fearing for his life and closes with him silently pondering the nature of life itself. Centered, like every episode, around the New Orleans restaurant Chez Louisiane —known simply as The Chez, pronounced “shez,” to its regulars — its 22 minutes detail an ongoing confrontation between the restaurant’s owner, Frank (Tim Reid), and a rag-clad homeless man (Abdul Salaam El Razzac) who calls himself simply a “bum” and takes up residence in the alley behind the Chez.

Startled by the visitor’s noisy late-night arrival, Frank calls the police on him, only to watch in frustration when the bum returns the next day and begins singing (if that’s the right word) outside The Chez during its lunch rush. Unsure what to do, Frank turns to his employees for advice then watches every possible tactic fail, from a threat of legal action to the suggestion of physical harm to an offer of employment to bribery — each attempt staged with expert comic timing by Reid and the series’ talented and deep supporting cast. Resigned to the situation, Frank ultimately begins feeding and talking to the bum, who accepts but doesn’t exactly welcome the overture. Then the bum disappears, and Frank finds himself just as troubled by the absence as the ongoing campaign of harassment. After belatedly recognizing the bum’s voice coming from a customer dressed in white, Frank hurries back to the restaurant’s bar to discover the man has vanished. Stepping outside, Frank finds only an empty street and a familiar-looking scrap of rag. He dusts it off then walks back inside The Chez.

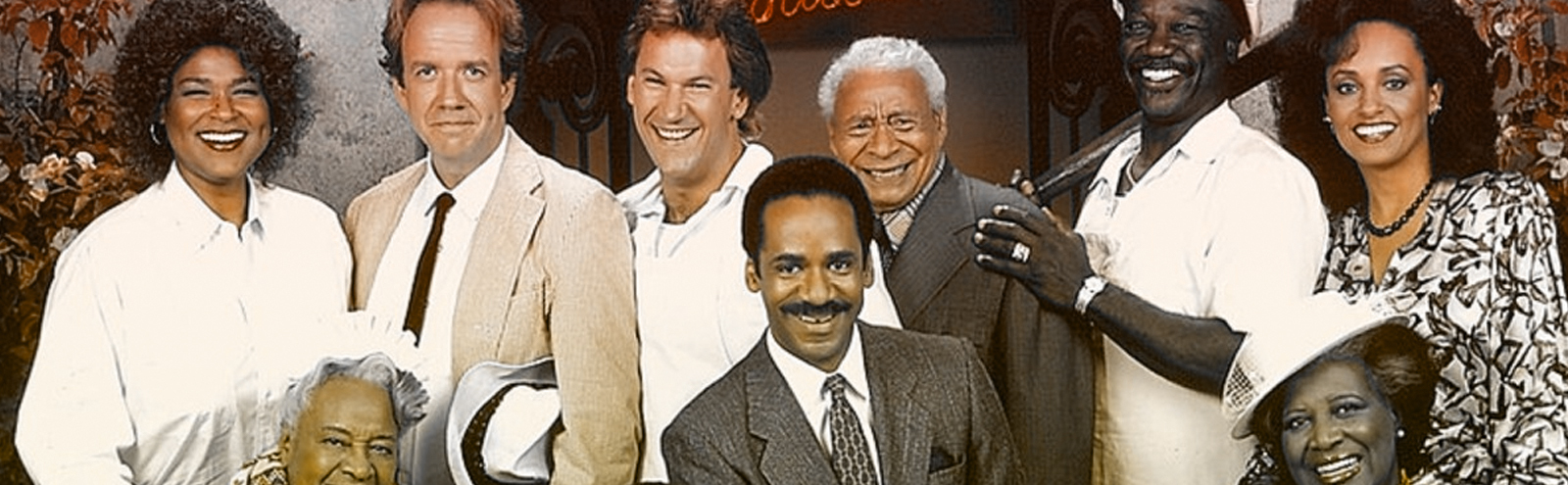

One of Frank’s Place’s best episodes, “The Bum Out Front” aired on CBS on January 4, 1988. Though it looked far removed from the more traditional fare surrounding it, it wasn’t a particularly unusual episode of the series, a single-camera comedy that freely incorporated dramatic elements, sometimes forgetting comedy entirely. Created by Hugh Wilson and executive produced by Wilson and Reid, who’d previously worked together on the Wilson-created sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati, the show featured a diverse but mostly Black cast that reflected the make-up of the city in which it was set. It was funny without ever straining for laughs — Wilson originally told the network he’d include a laugh track but later admitted he was lying — poignant without ever becoming maudlin and shot with graceful camerawork in umber tones then associated more with movies than television. It was a great show, but one seemingly doomed from the start. By the time “The Bum Out Front” aired, the series was already struggling in the ratings. In many ways, its run was defined by struggle. A show embraced by critics and largely ignored by viewers, it lasted a single season before cancellation.

It’s now easy to call Frank’s Place, a series whose stylistic and thematic ambition anticipated a more creator-friendly TV era, ahead of its time. Except, in some ways, it was very much of its time. In the fall of 1987 network TV was ready to make some changes — or at least thought it was. Fall TV previews buzzed about the coming of the “dramedy,” a hybrid format that broke with the set-up/punchline/everybody-hugs-at-the-end format of the standard sitcom, bringing cinematic touches to half-hour shows that mixed elements of comedy and drama. Where once there were no dramedies, suddenly there were many, shows like The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd, Hooperman, and The Slap Maxwell Story that resisted easy definition but attracted a new label.

The turn “dramedy” had been around for a while, even if it had never really taken root. Lucille Ball used it to describe her acting style and ABC briefly tried to use it to describe the short-lived ’70s series FutureCop, in which Ernest Borgnine played a human police officer partnered with an android. In 1987, however, the term was suddenly everywhere. “I don’t think any of us had a summit conference and colluded to come up with this kind of trend together,” NBC Entertainment president Brandon Tartikoff told the New York Daily News. But it could feel a bit like they had. Tartikoff also admitted that the search for something new had much to do with a sensed threat from cable, saying “There are clear signals that just putting on the same old shows is only going to exacerbate that problem.” Nonetheless, the dramedies of ’87 all struggled in the ratings. (The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd enjoyed a five-season run, but only after moving to a cable network.) In some ways the format outlived the term, paving the way for shows like The Wonder Years and Doogie Howser, M.D. that didn’t make a big deal about labels.

Paving the way for the future did little to help Frank’s Place during its run, of course, but its short existence hardly diminishes its accomplishments. The series used a familiar fish-out-of-water premise as a jumping-off point for seemingly any sort of story Wilson and a writing staff that included playwright Samm-Art Williams and well-traveled sitcom veteran David Chambers wanted to tell. That ranged from a raucous holiday episode in which Frank joins his lawyer and friend “Bubba” Weisberger (Robert Harper) for a fraught Hannukah celebration to a flashback episode detailing the triumphs and temptations of The Chez’s resident man of God/hustler, Reverend Deal (a showcase for series standout Lincoln Kilpatrick), to the Emmy-winning “The Bridge,” in which a customer’s seemingly-drunk driving accident threatens the restaurant until later revelations spotlight some of the indignities of growing old and sick without money in a country with a clear-cut divide between haves and have-nots.

A Boston professor who inherits the bar from the father he never knew, Frank provides an outsider’s perspective on the show’s colorful but never cartoonish depiction of New Orleans. Though he only reluctantly takes over the business — pushed by a voodoo curse organized by The Chez’s elderly waitress emeritus Miss Marie (Frances E. Williams) — the place quickly wears down Frank’s resistance. The presence of Hanna Griffin, a charming mortician played by Reid’s real-life wife Daphne Maxwell-Reid doesn’t hurt, nor does the staff’s eagerness to adopt him as one of their own, even as they laugh at his naïveté about New Orleans and the restaurant business. The supporting cast includes everyone from Charles Lampkin, an actor from the earliest days of TV in his final role, to Don Yesso, now an experienced character actor, then a Louisiana high school football coach Wilson took a liking to after meeting him on an airplane.

Despite being championed by critics, the show never found its footing. CBS bounced it around on the schedule and pulled it for weeks at a time. Wilson came to see its end as inevitable. Speaking to the Television Academy Foundation in 2015 he recalled, “I knew it was coming. You can only have the New York Times write so many things about you.” Reid, however, tells a slightly different story in the book Tim & Tom: An American Comedy in Black and White. Though it primarily focuses on Reid’s early-career partnership with white comic Tom Dressen, the book includes Reid’s account of a conversation with CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite who revealed that it was the series’ final episode — “The King of Wall Street,” in which a junk bond trader laments the sorriness of his profession during a trip to The Chez — that sealed its fate, thanks to CBS CEO Laurence Tisch’s taking offense thanks to his own Wall Street career.

Tisch may have killed the show, but time and copyright law have virtually erased it. Frank’s Place reruns aired on BET for a while in the ’90s but the series never made the leap to DVD when seemingly every show ever made was receiving full-season box sets (even Hooperman). And apart from some VHS-quality YouTube uploads, it’s never been available on a streaming service, held up by music rights issues. (Similar problems plagued WKRP in Cincinnati.) You could think of it as a missing link between what TV was and what it became, but that too seems unfair. Frank’s Place was determinedly its own show for as long as it lasted. Then, like the Chez’s uninvited guest, it disappeared, leaving those who remembered it to puzzle over where it went, what it meant while it existed, and what might have happened if it had stuck around a little bit longer.