For years, organized religion was mostly a source of derision for mainstream Hollywood, and, justifiably, for liberals in general. Ronald Reagan and Jerry Falwell spent much of the 80s and 90s weaponizing evangelicals against progressive causes far and wide, even on issues that didn’t seem to have much to do with God, Jesus, or the Bible. It was also rich with irony, considering Falwell’s Moral Majority was formed in 1979 expressly to get Jimmy Carter out of office, even though Carter was a born again Southern Baptist from Georgia and Reagan a Hollywood actor whose wife had a personal astrologer (not that pointing this out ever accomplished much).

The split only seemed to grow, through abortion, AIDS debates, and the satanic panic in the 80s and 90s, and on into the Bush/Ashcroft era, when being born-again was practically a prerequisite for a Republican candidacy. In return, the prevailing attitude among the moneyed liberal camp, which has long been closely associated with the creative class in the movie industry, was a Neil DeGrasse Tyson-esque kind of pedantic scorn, a teacherly identifying of holes in religious logic and flaws in the ideology. This seemed to peaked with the release of Bill Maher’s 2008 documentary Religulous and the publication of Richard Dawkin’s 2006 much-read book The God Delusion. Organized religion and erudite professional liberalism seemed permanently at odds.

Yet the “smug atheist” eventually turned into as much of a punchline as the 80s church ladies had been. Even in times of plenty, professional class liberalism failed to offer adherents much in the way of meaning. Sure, we could clown the born again and skewer their hypocrisy, but what did we get for being right? An Office Space existence of blandly comfortable corporate servitude? Like many a rural overachiever, I went from feeling hemmed in by the “Bible thumpers” I grew up surrounded by as an adolescent to begrudgingly envying their sense of community as an adult.

This idea of bland suburban living being its own kind of comfortable hell was rampant in late 90s cinema, from Fight Club (1999) to Donnie Darko (2001). 9/11 seemed to postpone that mass soul-searching, in those early days offering a sense that maybe this tragedy would sow the seeds of the kind of shared purpose that we assumed our WWII-generation grandparents had had (Dan Taberski’s 9/12 podcast brilliantly explores this phenomenon).

That hope quickly faded, and it was all but gone by the time we got bogged down in Iraq. In “Johnny Cakes,” perhaps my favorite episode of The Sopranos, released in Spring 2006, Patsy Parisi and Burt Gervasi try to shake down a Starbucks-esque coffee shop for protection money, under the guise of “The North Ward Merchants Protective Cooperative.” The manager patiently explains that “every bean has to be accounted for” and everything has to go through corporate. If they beat up this manager, the remote higher-ups will just replace him with another local stooge. A defeated Parisi exits the coffee shop, shaking his head sadly and grumbles, “It’s over for the little guy.”

It’s a hilarious sentiment coming from a professional extortionist, yet hard to argue with the inherent truth of it. It’s easy now to get nostalgic about the days when Starbucks, Jamba Juice, and Blockbuster (the latter of these also appear in “Johnny Cakes”) were the big villains of the day. But even in those times of relative prosperity that prosperity seemed crushingly bland.

Astute pedantry felt like a much more viable ideology when times were good. My generation entered adulthood being told that a decent work ethic and a good education promised at least a comfortable existence, if not necessarily a fulfilling one. The bloom came off that rose some time around 2008, when even the educated classes lost any guarantee of security.

In these days of fractured, expanded universe culture war, Donald Trump has somehow become the unifying champion of evangelicals. This despite being a queeny, twice-divorced New Yorker who, when asked his favorite Bible passage, famously responded: “two Corinthians, that’s the whole ballgame, right?”

It would be a very girl’s-dorm-art choice of scripture, even if he hadn’t bungled the title. He quite plainly has never been religious and probably even most of his evangelical supporters would admit this.

All of which is to say that the conditions were ripe for Hollywood to form a less adversarial relationship towards religion. There are signs that this is already happening, or at least that liberals want it to. Mostly overlooked in the debate over Adam McKay’s climate change satire, Don’t Look Up, was its treatment of religion. (Even I glossed over that aspect of it, it just didn’t fit into a review).

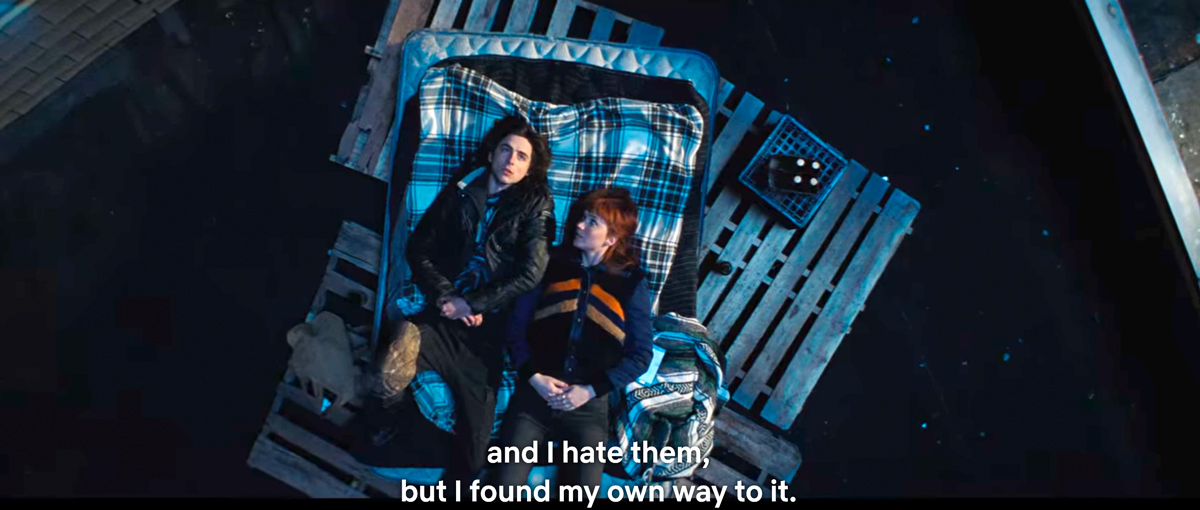

About halfway through the film, the hero, Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence), a doctoral student who discovers the planet-killing comet, meets a squinty little skater named Yule, (Timothee Chalamet). After hooking up on a pile of pallets behind a liquor store, Kate asks if he believes in God. “Yeah, I mean my parents raised me evangelical,” Yule answers. “And I hate them, but I found my own way to it eventually.”

He swears her to secrecy. “I won’t tell anybody,” she says “Actually, I think it’s kind of sweet.”

Later, after the billionaire tech magnate’s plan to mine the killer comet fails and it’s about to destroy the Earth, Kate and Yule get together with Dr. Mindy (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Dr. Teddy Oglethorpe (Rob Morgan) at Dr. Mindy’s house for one last family dinner. With little experience in the saying-grace process, the irreligious scientists turn to Yule, who closes his eyes and earnestly asks God for his love to soothe them through these dark times as they all join hands. “Wow, Yule’s got some church game,” Oglethorpe beams.

In a movie that was otherwise, and maybe crucially, lacking in sweet moments, this one lands. It’s hard to think of a more obvious symbolic olive branch between secular Hollywood and evangelicals than this scene — essentially a tacit admission that “science is real” (in the words of that obnoxious yard sign) is cold comfort when you’re actually facing extinction.

Sure, liberals have long had crystals and bee pollen and cold-pressed juices (their own forms of magical thinking), but Don’t Look Up invokes evangelism, specifically and by name.

The sequence preceding the dinner is equally loaded. Dr. Mindy receives a phone call from President Orlean (Meryl Streep) who informs him that Earth is about to be destroyed — but she has saved seats for his family on a spaceship built by the Jeff Bezos-esque tech magnate (Mark Rylance). Top figures in government and the tech industry plan to escape the ruined planet and freeze themselves until they find a new habitat. Dr. Mindy tells her thanks but no thanks, choosing instead to die with friends and family rather than potentially live with the rich and the powerful on some new unspoiled rock out in the galaxy.

I’m old enough to remember when the dominant rejoinder to evangelicals, at least among the artistic class, was something along the lines of “if Heaven is full of joyless assholes like you, I’ll take hell.”

It was a sentiment to which I probably would’ve subscribed myself at the time, and yet this scene turns it on its head with elegant symmetry. Dr. Mindy effectively skewers the new secular religion with a ruthlessness that would’ve made George Carlin proud: “If colonizing space and repopulating humanity means living forever among the alabaster princelings of the metaverse like Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg, I’ll die on Earth.”

In a movie that doesn’t always work, with satire that occasionally feels dated, Don’t Look Up‘s final few scenes feel both cathartic and prescient.

While Don’t Look Up is a movie with new ideas about the role of religion in the present, another film attempts a fresh look at the past. To that end comes The Eyes Of Tammy Faye, a biopic of Tammy Faye Bakker directed by Michael Showalter, originally released in September but which just hit HBO Max this month.

When I was growing up, I remembered Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker as, basically, weird freaks, consciously or subconsciously folded into the “greedy pastor/sex hypocrite” file along with so many other demagogues. “Crying TV evangelist” was its own kind of cliché. And again, this wasn’t without justification, given Jim Bakker’s conviction for fraud, the rape allegations against him by Jessica Hahn, his possible homosexuality, etc. The Righteous Gemstones is a winningly absurd portrayal of basically the same milieu.

The Eyes Of Tammy Faye, written by Abe Sylvia, based on the 2000 documentary of the same name, urges us to consider a more sympathetic view. It largely sidesteps the thorniness of Jim’s legacy by focusing on Tammy Faye, who at least has a modicum of plausible deniability for her husband’s antics. In Showalter and Sylvia’s hands, Tammy Faye becomes the painted face of what evangelical Christianity could look like, unshackled to political conservatism as it has become. The centerpiece of the film is Tammy Faye’s 1985 interview with a gay pastor named Steve Pieters, who was battling AIDS at the time.

Through tears, Tammy Faye (Jessica Chastain, in easily her best role) asks Pieters (Randy Havens) about coming out to his parents. “I think it’s very important that we as mom and dads love through anything,” Tammy Faye crackles, her face shining with both tears and garish makeup. “And that’s the way with Jesus, you know? Jesus loves us through anything.”

“Jesus loves me,” Pieters replies, earnestly. “Jesus loves the way I love.”

Whatever else the movie glosses over about Tammy Faye (I’m sure it’s plenty), it’s hard to argue the bravery of interviewing a gay Christian with AIDS on Christian TV at the height of the AIDS scare. (The way the movie tells it, Jerry Falwell, a man in part responsible for evangelism’s association with modern conservatism, was just off-camera, trying to pull the plug the whole time). The obvious question the whole scene raises is, why is it so hard to imagine an evangelical preacher preaching this kind of acceptance today when it already actually happened almost 40 years ago?

Is the movie a case of Hollywood trying to retcon evangelical Christianity in its own image? Certainly, to some extent, it is, but there seems to be sufficient justification. That Pieters, who was diagnosed with both full-blown AIDS and terminal cancer in 1985, is still alive today seems miraculous, even to the secular.

Tammy Faye also makes for a refreshing kind of hero. Jessica Chastain plays her as someone who mostly seems like a nightmare to be around — the “too loud” girl in the choir in every situation — but paradoxically the kind of person society could probably use more of. In the age of uncompromising, win-at-all-costs boy and girl boss protagonists (which is to say, most of Aaron Sorkin’s output and most of Chastain’s filmography), a terminal oddball with superpowered empathy is a nice twist. She wins not because she’s calculating or worldly than anyone else, but simply because she’s nice.

I’m not naive. I know this isn’t the first time Hollywood has dabbled in humanizing evangelicalism. Nor do I imagine that this is the first chapter in some glorious future where evangelical Christians and secular artists walk hand in hand toward an edifying, less judgmental conception of God. It feels more like what we’re witnessing is simply mass culture starting to acknowledge the limits of the “smarter management” brand of liberalism. That maybe the way to win an argument with someone who appeals to baser emotions isn’t to fact check them.

It’s hard to be optimistic about much these days, but I feel at least slightly hopeful about the signs that, after years of back and forth lib and MAGA ownership, maybe we’re starting to realize that these aren’t appreciable assets. Or maybe billionaire, utopian tech lords and divisive opportunists just make better villains than your average dope trying to find meaning in their existence.

Vince Mancini is on Twitter. You can access his archive of reviews here.