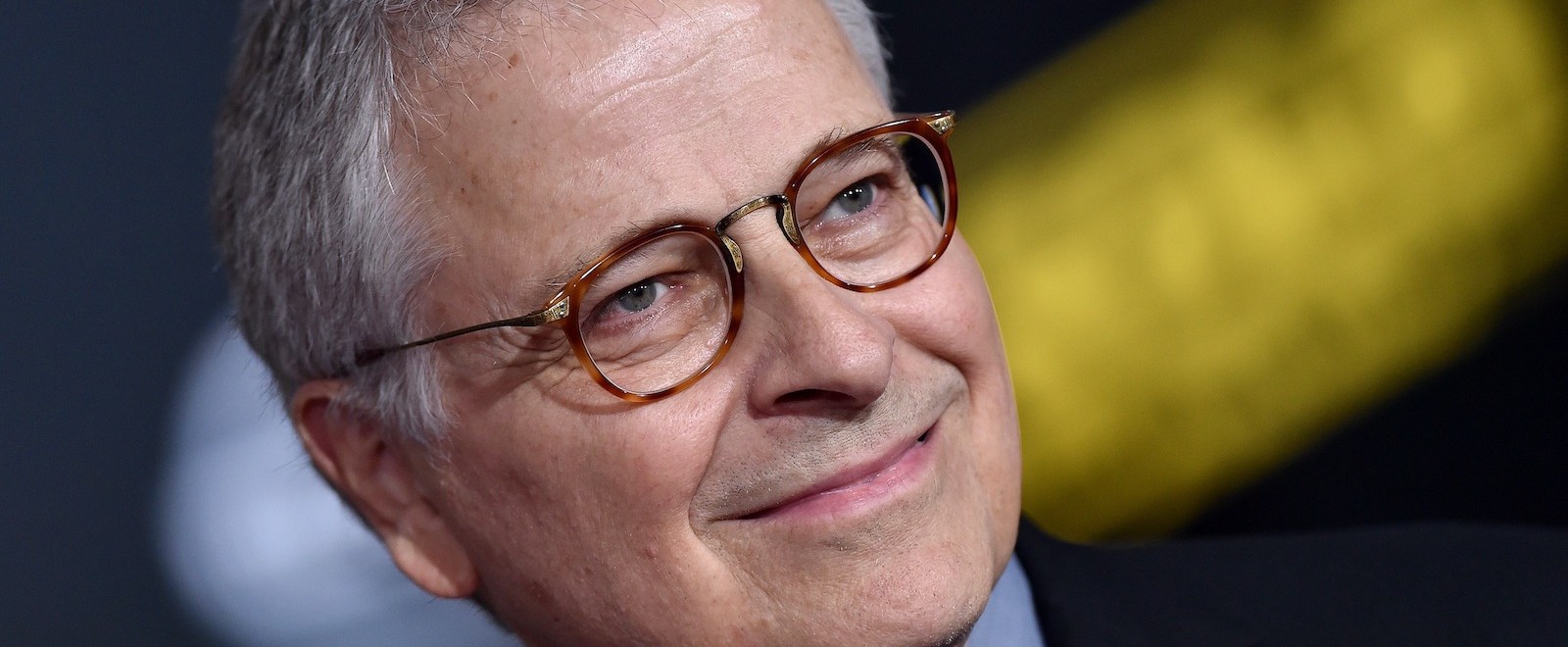

On the surface it makes sense that Lawrence Kasdan – you know, the guy who wrote Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi, The Force Awakens and Solo – would do a deep dive, six-part documentary on the history of the special effects team at Industrial Light and Magic. Before this interview, for research, I read an interview with Kasdan from 1981 in Starlog where he was talking about how he was fascinated with the effects in The Empire Strikes Back because it’s the part of the movie he had the least to do with. And then it kind of hit: right, that makes sense. Kasdan has never actually directed any of these movies for Lucasfilm. And when Kasdan does direct, they are more character studies, like Body Heat, The Big Chill, and The Accidental Tourist. Anyway, my hunch was right that a big reason Kasdan wanted to make this project was because he, too, wanted to learn what it is, exactly, that goes on at ILM.

Kasdan’s series, Light & Magic (which is streaming on Disney+ as you read this), plays as a love letter to what these crazy geniuses used to have to come up with to make a shot work. There’s respect for what ILM does today with CGI, but Kasdan’s doc shows there’s something clearly missing today. Before, there was something preposterous about the whole endeavor. They used to have painters, puppeteers and mechanics all working together for some crazy goal. Now it’s all done on a computer. One of the wild stories told in the doc is how ILM used actual maggots to make the Tauntaun fur in The Empire Strikes Back. (Something tells me maggots aren’t used very often these days at ILM.)

Ahead, Kasdan takes us through what he learned while researching ILM and takes us through his experience with them when he was helping to create some of the, still today, most popular movies of all time.

Before we start, during the worst part of the pandemic, I believe one night I tweeted at your son, Jon, “Could you pass along to your dad that we’re watching French Kiss and this movie rules?” Just in case you didn’t get that message.

[Laughs] That’s great. I’ve heard that a couple of times during the pandemic. It’s a pandemic movie, I guess.

You’ve heard that more than once?

It has a following, a devoted following.

Yeah, people really like that movie, but it’s not on streaming anywhere. We had to order the Blu-ray to watch it.

I think that must be due to the producing kind of thing. It was Polygram, and I don’t know why it’s not available.

You making this series on ILM is interesting. I read an interview with you in Starlog from 1981. You’re talking about The Empire Strikes Back and you’re complaining about how the arcs of C-3PO and Chewbacca were cut from your script, but you’re fascinated by the effects because that’s the thing you have the least to do with. So you’ve been part of this Lucasfilm family, but have never been directly involved with the effects. Now you’ve made a documentary about them. Does that make sense?

It makes absolute sense. I felt that way myself going in. I had this interest in visual effects and told them I’d like to do something about the history of visual effects. And then they suggested ILM because they already an arrangement with Lucasfilm. And I said, Oh, well that’s perfect. Because I felt like I was going back to a reunion. I knew a lot of these people, but not well, and I knew a little bit about the processes, but not much. But I’d always been fascinated that there was a place that housed all these geniuses. And I wanted to see, how did they get there? Who were they at? How do they get paid? What was it like between them, these brilliant people interacting all the time?

That Starlog interview is also interesting because it ends with you saying, “And that’s it for me with Star Wars. No more.” And they had to add an addendum with another interview from you going, “Oh, well that was wrong. I’m now writing Revenge of the Jedi.” I am curious when you wrote Jedi, were you more conscious of what ILM did? I know you had more time on that than you did Empire. Were you ever thinking, “Can they visualize what the stuff we’re putting down on paper?”

I never thought about what can they do, because the answer was “anything.” And you couldn’t know how they were going to do it, but they reached the point very early on in the life of the company where they could do anything. And the directors who were coming to them didn’t always know what they wanted, but they knew that this was the place they were going to get it. They had a vision, but it wasn’t necessarily terribly defined. But they knew that when they embraced ILM as a partner in the process, they were getting all this firepower. And they just loved it and they kept coming back. And that’s why they all wanted to be in the series and everything. There’s a real affection for ILM.

The ILM artists from that era, their enthusiasm is infectious. Harrison Ellenshaw, who paints Matte paintings, is hilarious talking about the painting he did under the tractor beam that Ben Kenobi has to turn off. “Why would that even be there on the other side of this thing where you could fall?” But who cares? It’s fun!

Absolutely. It’s something that people don’t give George Lucas enough credit for. But when I met George, when I took on the job of Raiders, and then when it suddenly got extended and he said, “Will you write the sequel to Star Wars?” He was a very … He’s fun. He was funny. He did all the voices. He was delighted. There would be a lot of tension and hard work to get A New Hope out, as you can see in the show, but he had actually achieved something he’d been working on for years. And he was in a good mood. And when we went to work on Empire, it was total fun. There wasn’t this pressure because there were people on payroll and stuff. I loved working with him. And Kershner would come in, he’d be an entirely different tone. And he had his own major gifts. And to see this very heavy Kershner meeting with George’s sensibility… George had studied with Kersh at USC. Kersh was very much this sort of the guru kind of guy.

I was lucky enough to interview Kershner right before he passed away. He’s fascinating.

He was a fascinating guy. And to see those two sensibilities meeting and they’re each turning to me and saying, “Well, how can we make that? What could you do? What could we write? How do we make that better?” It was really educational.

At one point in this doc, Lucas tells you, “Forget the story, forget the actors. It’s about movement.” In that interview in Starlog, you’re talking about Body Heat coming out soon and are kind of like, “Well, it’s a lot of talking.” Body Heat is incredible, but I’m curious what you think when he says that because your philosophy to filmmaking seems a little different than what he’s saying.

When anyone says that, I think, “Oh yeah, that’s a part of this.” That was not my area of concentration, but the things that hooked me on movies when I was 10 years old were that: they were action, they were movement. They were heroic characters who maybe had to be forced to do the right thing. But once they did the right thing, they were the best there were. And I think I have concentrated on interpersonal relationships, but always with an enormous affection for the action.

Silverado comes to mind as a movie of yours that does have action, but I’ve always wondered, you wrote Raiders, Empire, Return the Jedi, Solo, The Force Awakens, but you didn’t direct any of those. The movies you direct, you seem to eschew that and want to do other things. You direct movies like The Accidental Tourist. Is that by design?

I know. An opportunity finally arrived for me to do it in 1991 with Costner (The Bodyguard), but I had just started working on Grand Canyon with my wife. I made a commitment to do that movie and that movie turned out to be very satisfying, and I got to take part in the fun of The Bodyguard‘s success. To this day, there are road shows all over the country, all over the world. It’s a theater situation. It’s a musical and it never stops.

We rewatched it recently. That movie is incredible.

Yeah. The story just has a lot of appeal.

So, is it just circumstance that you’ve not really directed a movie that would need ILM?

Well, I made one and it was a disaster, so I don’t really think I’m good at it.

The doc gets into how after the first Star Wars, ILM had nothing to do. One of their only offers was a pornographic movie called Flesh Gordon.

Yeah. And they had no idea that this would go on forever. You know? And they were just sort of winging it. And no one had an idea at that moment, that 40 years later it would still be an institution.

The situation with John Dykstra is interesting. He’s running ILM, wins an Oscar for Star Wars, but when the company moves to San Fransisco, George Lucas does not invite him to come. He seems to still have trouble talking about that.

Well, I love that you pick up on that because that’s an important story. And when we started out, I’d say, Well, I’ve heard rumblings about this the whole time. I’ve never understood what happened. And I want this show to explain what happened and to the extent that we can get the naked testimony of the people involved, that’s great. And it turned out that everybody was willing to open up and talk about it.

Obviously, people who work on effects today are still extremely innovative. They’re the best at what they do, but it almost feels like there’s a preposterousness that’s missing today how they came up with ideas for things. Is something missing because that preposterousness is not there? I don’t know if that’s the right word or not…

No, there’s no question that … It’s like a lot of things that have passed. I liked it better when you’d go downtown, you could walk from store to store, there were no malls. That kind of thing. It was a different world. It was a more innocent world. And you could run into people on the street. That doesn’t happen when you pull into a parking lot with 4,000 spots. And this is comparable to that. It was handmade. It was a handmade industry. And the people that were thrown together in the beginning didn’t really know much about movies and that wasn’t really their primary interest. A lot of them were mechanics or sculptors or painters. And they all got thrown together for this brand new enterprise, something that didn’t really exist before that. There had never been this job in this generation. Oh, we take a group of a motley crew and put them together and they all have special skills.

Something you did, you’re talking to Kim Smith from ILM and she’s talking about ILM then versus ILM now with computer effects. And she just says, “Well, so be it.” But then you linger on her face and she doesn’t look very happy. And you leave it there for a bit. I mean, you can tell she’s thinking about the old times and how much crazy stuff they did.

Although what you just said is the highest compliment for the show because you got right to the heart of what I wanted it to be. And right from the get-go, I said, “This is not about the technology. This is about the people.” I had never gotten an idea of what the people were like. What did they feel when they were there? And as the thing went through various phases and how alienated did they get? How much did they want to hang on? Or how many much did they say, “Well, this is just not for me anymore.”?

Like I said, the people who do effects today, they’re the best at what they do today, but I really doubt today they’re using actual maggots to make Tauntaun fur. I had never heard that before. That is truly crazy.

That is maybe my favorite story in the whole show. I love it. And the more we understand, what he’s saying is outrageous and funny! And yet they were just concentrated on this problem. And that was the solution. I love that they took that kind of ad hoc solution to things. You don’t get that feeling today. You get the feeling like, “Oh, we got to write another program.” You got to do a hair-in-water program. You know? That’s not what was going on then.

‘Light & Magix’ is streaming now via Disney+. You can contact Mike Ryan directly on Twitter.