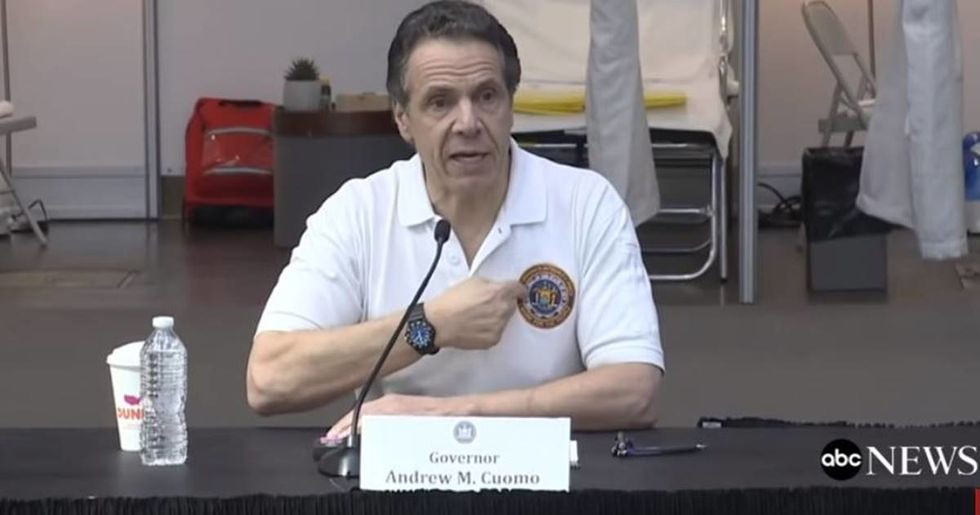

At a recent press conference, after his brother Chris was diagnosed with COVID-19, New York governor Andrew Cuomo kept reiterating two sentiments: “We’re all in this together,” and “This virus is the great equalizer.”

I understand the sentiment. I’ve said and written the “We’re all in this together” line several times myself over the past few weeks.

And in one sense—an important sense—it’s true. This pandemic is impacting the entire planet like nothing we’ve seen in our lifetimes. No one is untouched by it in some way. Anyone, rich or poor, can get sick and die from this virus. In that sense, it unites us as human beings, and I hope it will awaken us to our essential oneness.

But Cuomo was wrong on the second point. The fact that this is an equal opportunity virus doesn’t make it “the great equalizer.” The coronavirus pandemic doesn’t equalize anything. In fact, it merely highlights and magnifies our existing inequalities.

I’ve been thinking lately about the sinking of the Titanic. Those 2,240 passengers and crew members were on that boat together. Everyone was a part of the fear and the tragedy as it sank.

They were all in it together. No one escaped the terror. They were all touched by it.

But they were not touched by it equally.

Gov. Cuomo seized the historical moment with a rousing speech to the National Guard: This is a ‘rescue mission’

assets.rebelmouse.io

Passengers aboard the Titanic ranged from some of the wealthiest people on Earth to third-class steerage passengers, who were mainly working-class immigrants. And during the voyage, the third-class passengers had to stay in their designated area of the ship, which was gated off from the top three decks where the wealthier passengers hung out. Ship stewards could open the steerage gates in an emergency, but otherwise, they stayed closed.

In the chaos of the ship sinking, some of those gates never got opened, which prevented some third-class passengers from getting to the deck with the lifeboats. Those folks drowned trapped in their assigned place, the only place they could afford, without even a fighting chance of survival.

The fact that they were “all in it together” didn’t change the structures in place before the tragedy—structures that directly impacted their fate on that ship.

Of course, as we know, there weren’t enough lifeboats for all of the passengers anyway. Barely half, in fact. Having an adequate number of lifeboats would have made the first-class top deck look “cluttered,” which the wealthy ship owner didn’t want for his wealthy passengers. Besides, the ship was supposed to be “unsinkable.”

And so it was that the economic inequality clearly delineated in the ship’s voyage played out in its sinking as well.

Because they were already on the upper decks, wealthy passengers got to the lifeboats first. Some were lowered into the ocean and rowed away from the ship before their boats were even full.

Despite the standard “women and children first” rule of saving people at sea, 52 out of the 79 children from third-class died in the sinking—about the same percentage as first-class men.

Overall, 61% of first-class passengers, 42% of second-class passengers, and 24% of third-class passengers survived.

Some might say, “Well of course fewer third-class passengers survived—they were farther from the lifeboats,” and that’s exactly the point. The wealthier passengers had an advantage from the get go. The poorer passengers had farther to go, and some of them were cut off completely.

The Titanic passengers were all in that boat together, but that didn’t mean they were equally impacted by its sinking. And we will see the same impact of inequality play out in this pandemic as well.

It’s true that wealthy people aren’t immune from the virus, and some will die. But they still have an advantage from the start. Wealthy folks have access to the best medical care and the ability to afford it. For goodness knows what reason, the wealthy appear to be able to get tested for the virus even without showing symptoms, while the average American has a hard time getting a test unless they are ICU-level ill.

Poor people are starting at a disadvantage, as they are a) more likely to have underlying health conditions, b) less likely to seek medical help early over fears of not being able to afford it, and c) more likely to work in the vital-but-low-paying service industries we are now relying on to feed us, keep our grocery stores and hospitals clean, and transport our food and garbage, putting them at higher risk of exposure.

Wealthy nation offers concrete rectangles to people without homes during pandemic

Shaun King/Instagram

So yeah. We’re all in this together. But that doesn’t change the fact that our vast economic inequality means this pandemic will affect people differently. This will be true both here in the U.S.—where 1 in 9 Americans in our “booming” economy were living below the poverty line—and around the world, where 1 in 3 do.

We learned from the Titanic that disasters don’t play out equally, even if they impact everyone. We will learn the same thing with this crisis, and with every tragedy that follows until we make some fundamental changes in our economic systems.

If we want to claim that we’re all in this together, let’s make sure we have enough lifeboats for everyone and do something about the gates that keep people trapped in the lower decks before this ship sets sail again. Since we’ve clearly hit an iceberg and will need to rebuild the economy anyway, perhaps we can purposefully build it in a way that works for all, not just those on top.