Previously on the Best and Worst of WrestleMania 36: Bill Goldberg lost a tackles and body slams competition to Braun Strowman, John Morrison won a climbing match by falling, and AJ Styles was actually murdered by The Undertaker in the Bone Zone.

If you haven’t watched part two of this year’s WrestleMania yet, go do that now. Remember that With Spandex is on Twitter, so follow it. Follow us on Twitter and like us on Facebook. You can also follow me on Twitter. BUY THE SHIRT.

One more thing: Hit those share buttons! Spread the word about the column on Facebook, Twitter and whatever else you use. Be sure to leave us a comment in our comment section below as well. Feel free to peruse the WrestleMania 36 tag page if we missed anything.

Here’s a special, one-match breakdown edition of the Best and Worst of WWE WrestleMania 36 (1.5 of 2) for April 5, 2020.

Why Must Fireflies Die So Young?

I’m not sure how to say this, exactly, but the Firefly Fun House match on night two of WrestleMania 36 was art. I’m not saying that to be twee, or to do a hacky “actually pro wrestling is an art form you philistines” thing. I truly believe it was art, because unlike some of even the best professional wrestling matches, it challenged me. It required a second viewing, and a frame-by-frame breakdown to understand it on the level upon which I believe it was intended to be understood. It contains complex character work, introspection, and a deep history lesson from WWE, a company we (and especially I) don’t give credit to or expect to present ANY of those things in its product.

I’m going to try to break it down here and make sense of it, both for you and for myself. Keep in mind that I could be completely off on all of this, but hey, it wouldn’t be the first time. Stick with me until we get to the end.

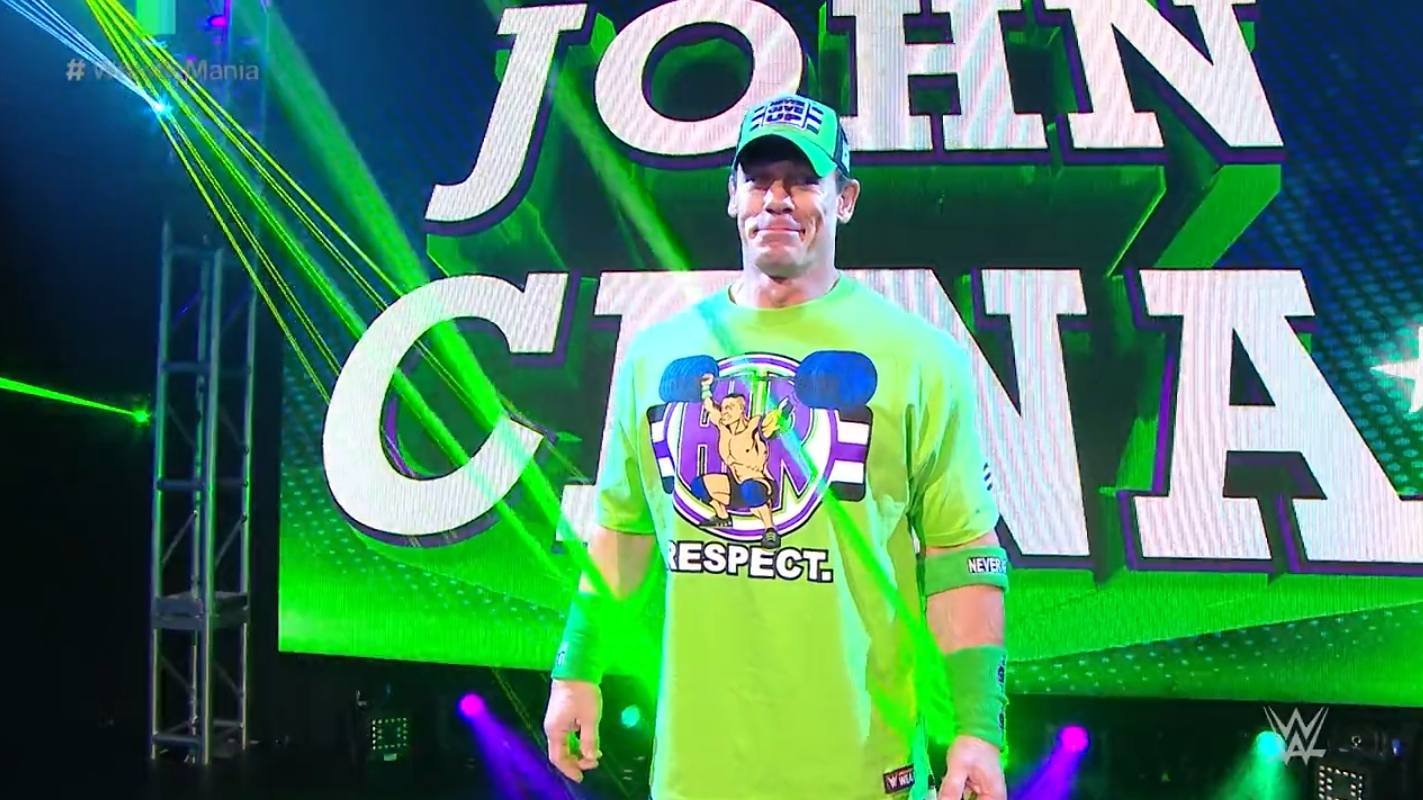

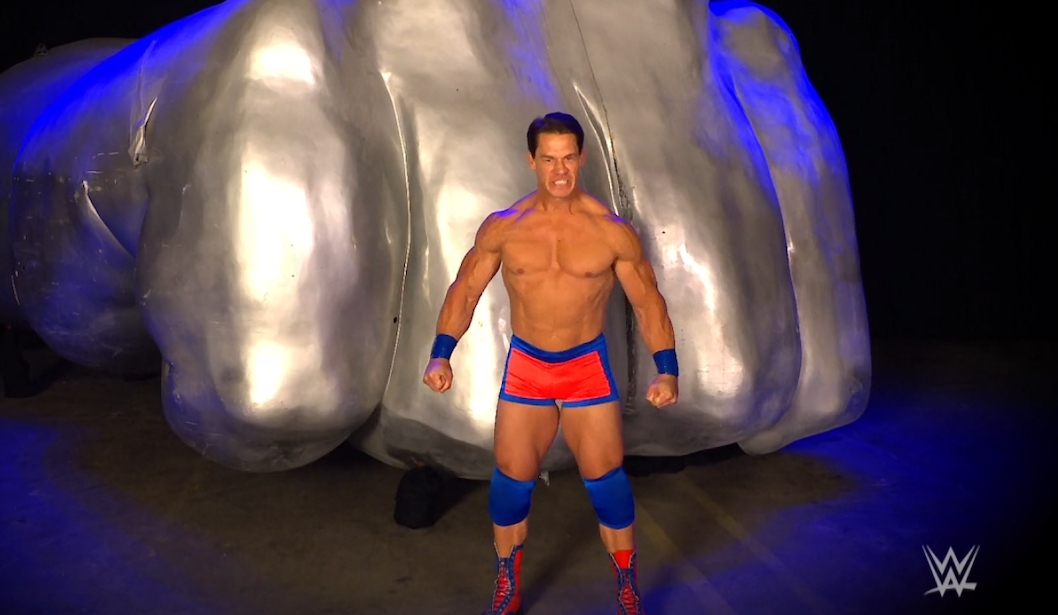

The match — short film, whatever — opens with John Cena entering into the weird, empty Performance Center. If you watched Smackdown, you know he’s more shaken by this than most. Characters that aren’t allowed to have “free will,” so to speak, just show up and do their entrance animations and still play to an empty crowd, because the people at home are watching and they want to put smiles on people’s faces. Cena, who has always walked a tightrope between being super serious and sarcastically self-aware, doesn’t know how to handle it. He left for Hollywood and came back to … this? What even is this?

On Smackdown, he realized his “talking to the camera man” bits were audible now. “Now they can hear us talking. Welcome everyone, to Smackdown … on FOX!” Here, he’s not just walking into an empty gym Smackdown … he’s entering into an empty gym WRESTLEMANIA. That’s got him shook already as a guy who has done WrestleMania entrances involving clone armies, gospel choirs, gangsters with Tommy Guns, Tokyo drifting sports cars, and marching bands. Plus, he’s going into something called a “Firefly Fun House Match,” only kayfabe 46-ish hours after being confronted by puppets and haunted by a teleporting guy running two concurrent monster gimmicks. Cena’s a good proxy for the audience here, because he doesn’t know what the shit’s going on either. He tries to do a sarcastic, “welcome to WrestleMania!” call — most famously attributed to Vince McMahon, which we’ll call back to later — and it’s immediately warped by Bray, in the Fun House.

This is where Bray finally sets the stage for what we’re about to see.

He reminds us that the Firefly Fun House is a place where Gods, monsters, angels, and demons are neighbors, and that the Fun House exposes your darkest urges and shows you who you really are. Bray: “Who are we really, and why do we do the things we do?” Think of it like Westworld, by way of Pee-wee’s Playhouse. The Firefly Fun House match is going to be a look who John Cena “really is,” as he faces his “most dangerous opponent.” Himself. Adventures of Link style.

Bray leaves through the “abandon hope all ye who exit here” door, which we’ve seen him enter from numerous times. That’s where we’re having the “match.” In a matter of moments Cena’s been involuntarily teleported there, and follows after Bray on the instructions of a naive, immortal rabbit puppet. There’s been a lot of conversation about how each puppet represents part of Bray’s psyche, and I’m pretty sure Ramblin’ Rabbit is his love of pro wrestling. It’s the smallest puppet, always being victimized by the others, who marks out for all the wrestlers he talks to and can’t seem to die, no matter how many times people try to kill him. It makes sense that a pure love for what they do will be the connective tissue here.

From here on in, the match becomes a meditation on Cena’s entire wrestling career, from beginning to end.

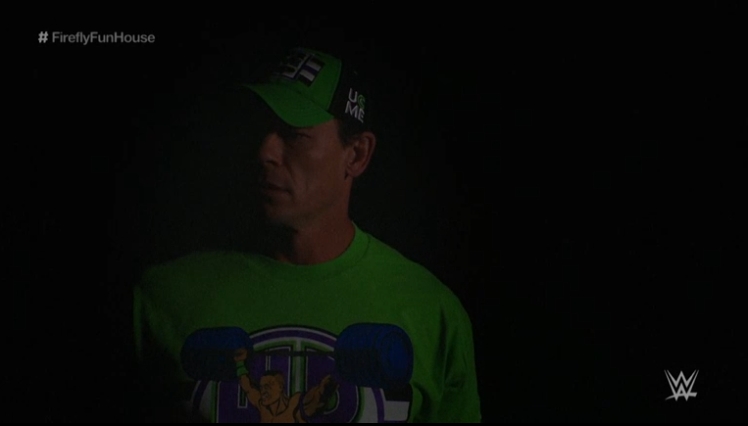

We begin with Cena’s creation. This is represented by Cena standing in a dark room, surrounded by nothingness, while a heart beats in the background. This is John before “John Cena.” His persona only exists in a dark void, waiting to be created. And who created him?

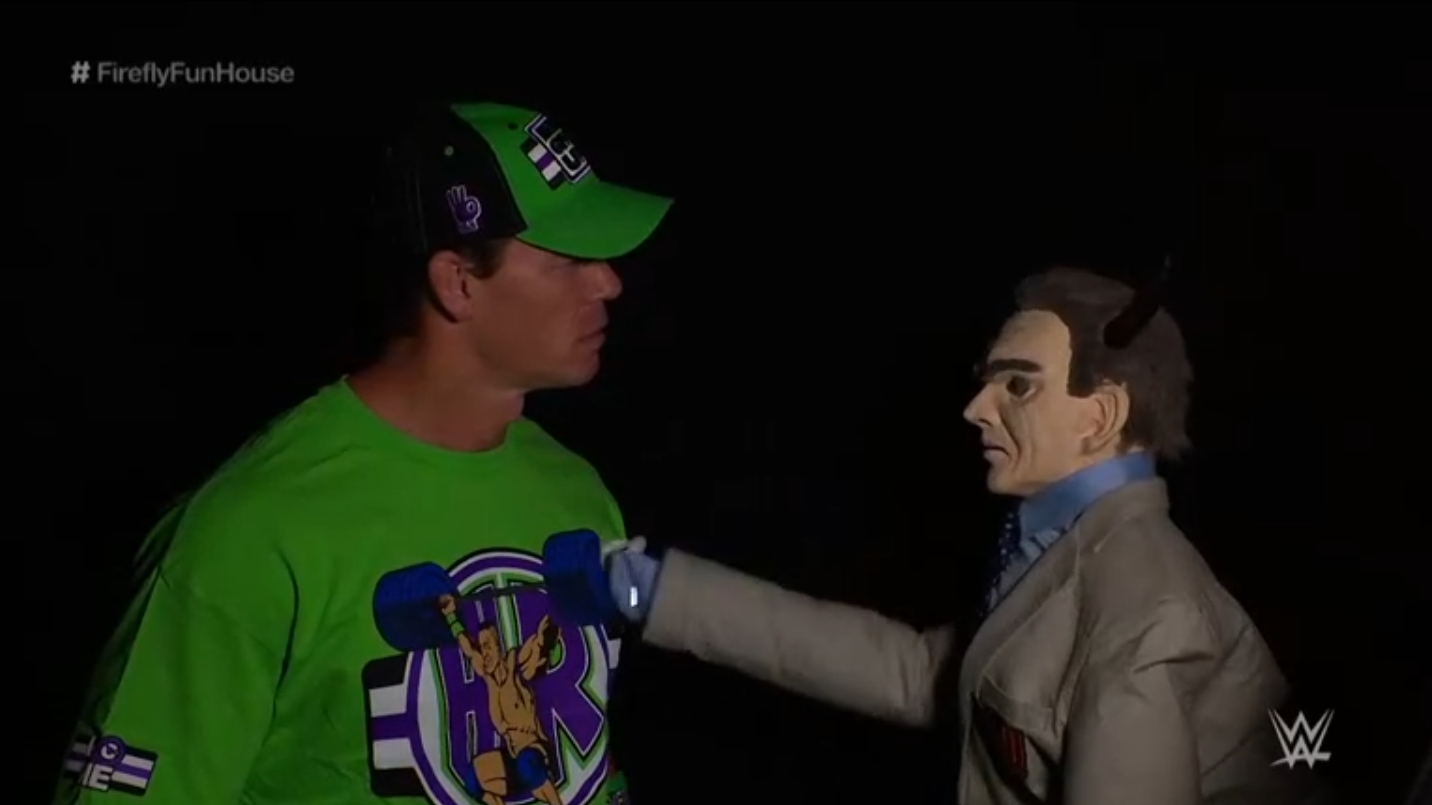

Vince McMahon, of course, represented not especially subtly by Wyatt’s money-eating “Boss” puppet. Puppet Vince launches into his declaration of “Ruthless Aggression” from the June 24, 2002, episode of Raw, where he overtly set the tone for the next 18 years of WWE’s top stars and heroes being defined by their willingness to be self-centered and violent to validate McMahon’s bizarre misunderstanding of and hapless attempts to recreate Stone Cold Steve Austin. Whoever steps up will have to give up themselves to become what Vince wants. “Do you have enough ruthless aggression to make the necessary sacrifices of mind, body, and soul, to be a success in this company? Show me, or you’re fired!”

Three days later, John Cena made his debut on Smackdown and declared that he, more than anyone, had Ruthless Aggression and was willing to do anything to prove it. He slapped an already legendary champion and Olympic gold medalist in the face to show it. He was everything Vince wanted, right out of the gate: handsome, stupid muscular, tall enough, heavy enough, inconsequentially aggressive and violent, and ready to pander to crowds with big declarative statements and hot pants he could change the color of to match their local sports teams. It didn’t work, though. In the Ruthless Aggression documentary series, he calls it the biggest mistake of his life.

In that same doc, Cena mentions that the character didn’t work and that WWE was already ready to just give up and let him go when his contract ran out in November. In the Firefly Fun House, this takes the form of Cena showing up in his rookie look, complete with the SMACKDOWN FIST that they’ve found and fished out of the archives. Cena does what he did back then; be hyped up, beautifully sculpted, and brutally confrontational despite not really knowing what to do yet, and not really having a character to speak of. He just keeps screaming “RUTHLESS AGGRESSION” and swinging wildly with missed slaps over and over, because that’s what he was told to do.

Bray rightfully asks him if this is what he wants to do with his life, and we get flashbacks of Cena as a little kid holding handmade belts to suggest that no, maybe it isn’t. He wanted to be a professional wrestler, you know? Not an awkward little action figure that Vince McMahon can use to punctuate his demands for unconscionable Alpha Male superiority and throw away when it doesn’t work like he wanted. But this is what he MUST do, because if he doesn’t make the “necessary sacrifices of mind, body, and soul” by completely losing himself in McMahon’s image of masculine perfection, he’ll lose his job. Which means that little kid who loved wrestling — John’s Ramblin’ Rabbit, so to speak — he’ll never even get the chance to live his dreams. This is the only game in town.

So wait, what IS McMahon’s image, exactly? For that, we have go back to the 1980s and Vince McMahon’s all-time shiniest show pony: Hulk Hogan.

As anyone who’s ever watched WWF or WWE programming knows, Vincent Kennedy McMahon has a predilection for enormous, abrasive, borderline immobile “body guys.” He wants you to look as good, sound as good, and DO as little as possible. Wyatt makes that differential clear. “That’s what being a stud is all about; having muscles, no matter what little talent you possess.”

If I’m putting this together right, I believe this is placed here to show that to succeed in WWE, Cena would have to emulate someone else. Vince McMahon’s assertion of Ruthless Aggression evokes an attempt at a new Stone Cold Steve Austin, a devil may care hell-raiser who kicks ass and lets God sort ’em out, but what he’s really asking for is another Hulk Hogan. Hogan was cruel. He was never a “good guy,” despite being a hero to children and crying fans. He was what Vince McMahon considered an Alpha Male. He was all about himself. He made himself look SO GOOD and be SO BIG and SO STRONG that even GIANTS couldn’t stop him. He was American exceptionalism. There’s a clear reason why Hogan’s notable enemies were either fat guys (King Kong Bundy, Andre, Akeem), foreign guys (Iron Sheik, Nikolai Volkoff), or arrogant smart guys who were nowhere as big or strong (Bobby Heenan, Randy Savage, Ric Flair).

To be this for Vince, Cena works out harder than anyone possibly could. He’s doing rapid-fire bicep curls and speaking in goofy 1980s promo lines to be literally anything other than himself, because the longer he’s doing this and the more of a product he becomes, the less he even knows what himself is. But he puts that emphasis on being a body guy until his arms give out and he “can’t do anything.” He tries to fight, but he can’t even lift his arms. I like to think this is symbolic of the prioritization of physical appearance and ego over skill and ability. Hogan could wrestle, but didn’t, because not wrestling worked. Cena got a reputation for “not being able to wrestle” because not wrestling worked better. He just did the five moves in a row and won. It worked in kayfabe, and it worked in ticket sales. People just wanna show up and clap at things they recognize. They don’t actually care how good at wrestling you are. “Wrestling isn’t wrestling,” right? It’s just a children’s show full of weird, screaming characters who keep hurting each other.

But I digress.

The other reason the “body guy” segment happens here, I believe, is because of how Cena’s always treated anyone who didn’t look as perfect as him like they were worthless. CM Punk wasn’t big and muscular enough. AJ Styles wasn’t big and muscular enough. Bray Wyatt, no matter how good of a wrestler and talker and character he is, gets lowered to the “overfed sex child of Wiz Khalifa and the WB frog.” You’re fat, and you look stupid. I’m muscular, and I look GREAT. Which makes me a HERO. I’m doing what’s RIGHT. I represent TRAINING and SAYING MY PRAYERS and EATING MY VITAMINS.

Bray, who might have not made this connection clear enough by showing up on Saturday Night’s Main Event behind the big blue cage and saying “brother” a bunch, brings all this home with the line: “Whatcha gonna do, brother, when you realize that Egomania has been running wild on you?”

Cena can’t stop, though. This is what he’s been told he’s supposed to do. But it’s October, and his contract’s up next month. He’s heard Rikishi and Rey Mysterio freestyling in the locker room, though, and he likes doing that, too. And there’s a Halloween episode of Smackdown coming up, so he decides to have a little fun and dress up like … well, he’s supposed to look like Vanilla Ice, but he looks more like Liberace. It catches on, and they decide to keep him on as a funny joke at the bottom of the card. The “Doctor of Thuganomics” is born.

Cena, unaware that Egomania has run wild on him, turns into a character that just says the meanest, most hateful, sexual, offensive shit to get a reaction. “If all I got is rapping, I’ll use it to my advantage.” He builds his legacy on insults, dick jokes, and ruthlessly aggressive gestures and move names (the “F-U,” a “fuck you” to Brock Lesnar; an STF called the “STFU,” as in “shut the fuck up;” the “Five Knuckle Shuffle,” a euphemism for masturbation, and so on) while slowly convincing himself that not only is he brilliant … he’s a hero. One of the most beautiful moments of this entire Firefly Fun House bit is stock sounds of children’s laughter responding to Cena making a boner joke they don’t get. That’s what the past 15 years of WWE was built on. Convincing kids that the best person was the one who could be the funniest, hurt you the most, and make you feel the worst.

On Smackdown, Cena made multiple jokes about how Bray Wyatt was a fat failure. Here, he raps that Bray is a, “slut for opportunity, blowing every chance,” and calls him Husky Harris — a chant that plagued Bray in the early days of his main roster character — to draw a direct line between the “real” Wyatt (a fat loser) and the characters he’s playing. It’s like when Cena called attention to the fact that Alberto Del Rio didn’t actually OWN all those cars, he just rented them, and wasn’t actually rich, this was just part of the show. Or when he made fun of people for working in other companies, didn’t make enough real-life money for the company, or even needing to write promo notes on their hands. Abject, popular cruelty. Cena seeks to hurt Wyatt personally for confronting him professionally, believing him to be entitled and ungrateful for the “chances he’s been given.” Because like anyone who struggled but then got rich and successful, Cena now believes HE succeeded ALL ON HIS OWN, and you’re weak if you can’t just do it too.

This is where things begin to turn. Wyatt points that he keeps working for opportunities and keeps having them taken away as John (the golden goose) gets unlimited, untouchable chances. He says what I and a lot of other people have been saying about John Cena’s character for more than a decade: “You’re not a hero, John. You’re a bully. You’re a horrible person. You take the weaknesses of others, and you turn them into jokes. You do anything for fame, John. Congratulations! You’re the man now, John! Poor lonely John Cena.”

In his career, Cena rode the popularity of his rapper to the point that it morphed into a troops loving, rah rah American hero who worked out, said his prayers, and ate his vitamins. He hated and destroyed everything that was a threat to his concepts of power, heroism, and self. They were also Vince McMahon’s, coincidentally. As Vince might say, “keep it up.” As time went on, the image of Cena’s character become more important and consequential than anything he was actually doing. Cena (the character, just to be clear) thought CM Punk was a fake hero of the people who was only in it for himself, because Cena was that. Punk told him he’d become a dynasty, the New York Yankees. Being hit with that sent Cena into a rage. Cena thought The Rock abandoned WWE to go make movies in Hollywood, because Cena wanted that. Rock told him he was a wannabe boot-licker, and Cena spent over a year trying to beat him up to prove him wrong. Cena went on a reality show and proposed to his girlfriend at WrestleMania because they’d be good PR beats, while he keeps getting older and older and realizing his entire personal life is interminably locked to his professional. His character doesn’t have any friends. He’s been mean to every friend he’s ever had. He’s buried a Boneyard full of people to protect his spot, and now he’s alone.

Or, as Bojack Horsemen might put it:

Wyatt, having been as honest and direct with Cena as a spooky kids show host whose body contains the spirit of a demonic shadow clown can be, tells Cena that this is his last chance to understand, and that the floor is his. It’s Cena’s “last chance” to get it, because if he doesn’t, they begin the endgame, and that’s where shit gets dark. Cena visibly considers what Bray’s saying, but only for a moment, before rejecting it. Instead of confronting himself psychologically and emotionally, John makes a deez nuts joke.

Because John Cena.

Enter: WrestleMania 30

At WrestleMania 30, Bray Wyatt was at the height of his career. He was wildly popular and critically acclaimed for the work he’d done in NXT and beyond. He was something special, rising up during a time when almost nothing felt special. “I was the color red in a world full of black and white,” he says. Pay attention, this comes back later.

John Cena had become everything he wanted. He was a dynasty. He proclaims to be a man of the people, but doesn’t listen when the people tell him they want something else. Look at the Nexus, for example. Look at him sauntering in to kill Rey Mysterio to win a WWE Championship moments after Rey’s already wrestled. Most importantly, look at WrestleMania 30, when Cena needed to put over this new character and make him, and just … didn’t. Cena just squashed the shit out of him. Most of us lost faith in Wyatt, and he spent the next few years in a weird downward spiral of unintelligible character work, bad matches, terrible ideas, a complete lack of confidence, and a number of angles aborted either because of circumstance, or because WWE just wanted out.

So here, Wyatt seeks to rewrite his own story by capitalizing on the recreation. He sets Cena up for Sister Abigal, but lets him free. “We both know that’s not enough to end it Superman. But this is.” At WrestleMania 30, there’s a moment where Cena has a chair, and Wyatt kneels in front of him with his arms out, begging him to “finish” him. Wyatt can’t beat Super Cena, so he’s going to go out swinging and at least affect some kind of permanent CHANGE in him. In real life, Cena just kept being Cena and won the match like it was nothing. He made some faces about it, but it didn’t register as any kind of sincere fear or effort, and the status quo was maintained. In the Fun House, Cena, out of hatred for all the truth he’s just had to sit through, chooses to rewrite this path and take the low road. He swings for the fences, but Wyatt disappears. Wyatt doesn’t need the pain. He needs to do what nobody else has been able to do before. He needs the satisfactions of that permanent change in John Cena.

John Cena did the unthinkable at WrestleMania 36. He turned heel. It was imaginary, so to speak, but he was presented with a clear argument suggesting he’s a terrible human being and instead of trying to fix those habits, he leaned into them. He wants to KILL Bray Wyatt for doing this. So to illustrate this, we go back to where it all began: Hulk Hogan.

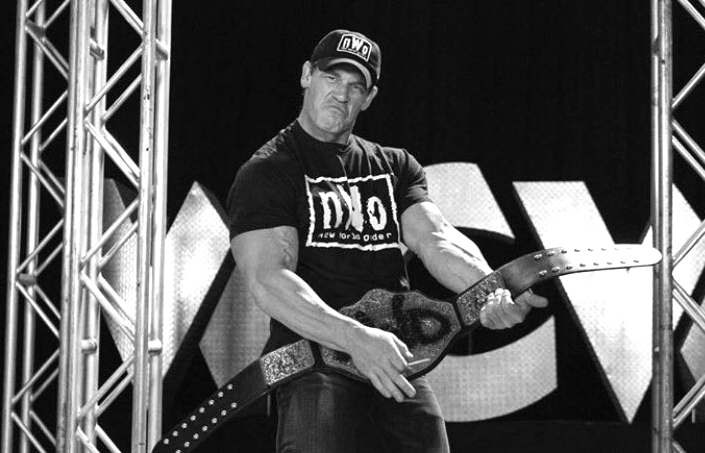

In 1996, Hulk Hogan shocked the wrestling world by betraying WCW and forming the New World Order. Hogan had been a “good guy” for the entirety of his WWF and WCW careers, and him being evil was, at least at the time, a complete impossibility. For the longest time, folks like me have been saying that a Cena heel turn, especially late in his career and after he’s gone through so much, would be just as good. It never happened, because again, nothing, not the hand of God itself, could make John Cena change. He hasn’t even changed his t-shirt in his past several appearances. He’s just this goddamn version of John Cena forever.

In the Fun House, we visit an alternate timeline where Cena turns heel. He does the worst thing you can do in WWE’s mind, still, somehow: go to WCW. So we’re suddenly on an episode of WCW Monday Nitro with John in an nWo t-shirt, with an nWo hat, and an nWo towel. He’s wearing Hollywood Black and White, to make the allegory clear. Wyatt, who is “red in a world of black and white,” is wearing a Wolfpac shirt. I LOVE that touch. Elseworlds nWo Cena, destroyed from the bottom up by his internalized corruption and delusion, listens to Wyatt lovingly introduce him in the style of Eric Bischoff and just ruthlessly, aggressively beats him to death anyway. The Vince McMahon puppet, watching from the announce table with a Macho Man version of Mercy the Buzzard, declares this, “good shit.” Shorthand, at least to “smart” fans on the Internet, for WWE’s worst ideas.

As Cena beats Wyatt to death, he’s confronted by his greatest failures in quick little cutaways. These are, in order:

- the “if Cena wins we riot” at ECW One Night Stand, which was the first recognized and most iconic expression of fan hatred for Cena’s character

- Edge cashing in Money in the Bank on Cena at New Years Revolution 2006

- the aftermath of his loss to Shawn Michaels in their legendary Raw match from April 23, 2007

- losing the WWE Championship to Batista at Elimination Chamber 2010

- losing to Miz at WrestleMania 27

- CM Punk’s “kiss goodbye” to Vince McMahon at Money in the Bank 2011, which once again suggests that Cena’s failures are Vince’s

- Cena being mopey on the ramp after his WrestleMania 28 loss to The Rock

- losing the title unification match to Randy Orton at TLC 2013

- getting murdered in spectacular fashion by Brock Lesnar at SummerSlam 2014

- leaving his arm band in ring after losing to AJ Styles at SummerSlam 2016, which was when Cena started taking more and more time off for Hollywood obligations

- putting over Roman Reigns at No Mercy 2017

- losing to Undertaker in minutes at WrestleMania 34 after spending weeks goading him on

Cena turns back into himself, realizes he’s not a fictional heel — he’s the actual heel — as evidenced by him brutally assaulting Huskus the Pig Boy, the most childish and innocent representation of Bray’s psyche. The part of Bray that still represents “Husky Harris,” and being a young up-and-comer who doesn’t fit the WWE mold … being put in place by the personification of what Vince McMahon wants.

Wyatt played to Cena’s remaining humanity (now that he’s separated himself from the wrestling business and no longer serves a purpose in his role as Superman enforcer of the status quo), and manages to actually, finally, MAYBE affect true realization and change upon the John Cena character by convincing Cena that he’s a bad person, and all the things Wyatt said about him were true. Cena instantly loses the nWo shirt and the fantasy, and is just back to being 2020, normal John Cena again. He stares down at his hands, because shit, Bray was right. He really was. We all were. Cena started off with good intentions, lost himself somewhere along the way, got everything he ever asked for, and ended up here. Everybody loves him, but nobody likes him. Imagine only realizing who you really are when you’re 42 years old, at the end of the career you sacrificed your mind, body, and soul for. All you have is ruthless aggression. That’s your one trait.

You’re the heel.

This is when The Fiend is finally able to be “let in.” Cena is broken. The Fiend “squashes” him with no effort, and we realize that Cena’s declaration that he was going to put a stop the most over hyped, over privileged, and overrated talent in WWE wasn’t about Bray Wyatt. It was about John Cena. Bray Wyatt counts the pin for The Fiend, and John Cena literally disappears, his image and perception shattered. At the end of John’s career, you can’t see him.

Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains.

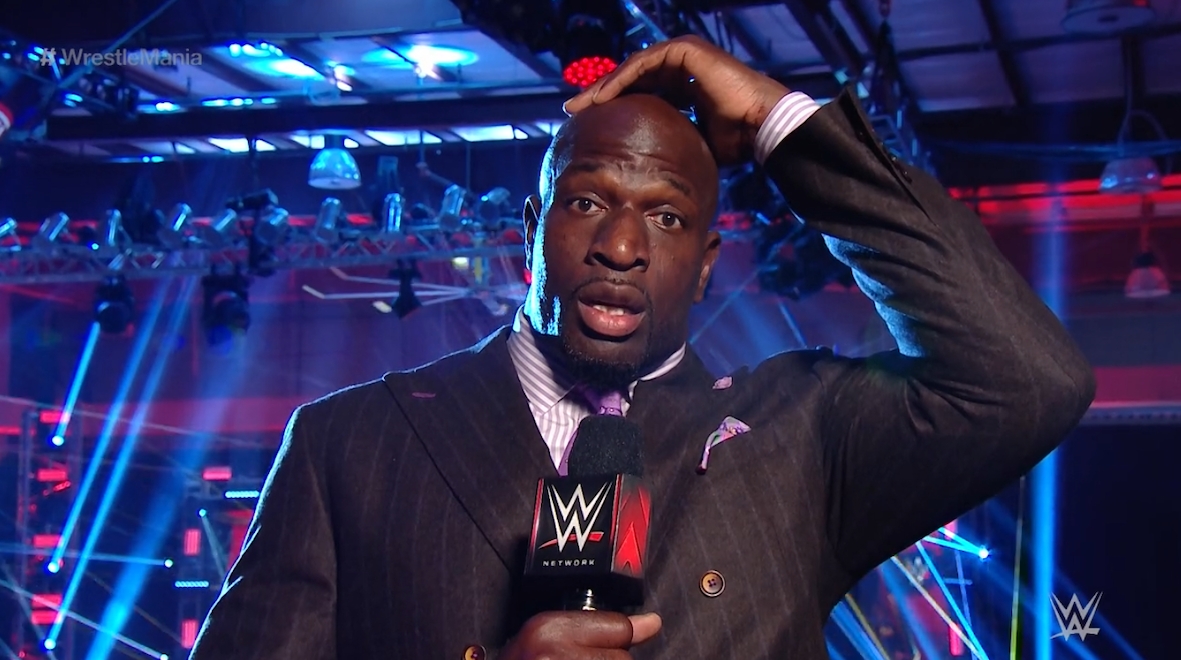

The next thing we see is Titus O’Neil, making this face.

The Boneyard Match on night one of WrestleMania was a really enjoyable, cornball combination of WWE and action movie concepts, but the Firefly Fun House was, as advertised, unlike anything WWE has ever done. It was deliberate, and thoughtful, and meditative. It took a look at itself, not with glorification or snide parody, but with sincere, open eyes. It said something about the characters involved beyond how good or bad they are, and it might have just given a real, honest purpose to 18 years of John Cena. I didn’t even cover all the references, like the Bella Twins nod, and there’s still probably so much left to find and contextualize.

It wasn’t a “good match,” but it was essential to our understanding of the medium, and the promotion that anchors it.

That’s good shit, pal.