The easy cliché here would be to point out that Russ Bengtson has forgotten more about sneakers than most of us will ever know. The problem with this particular cliché is that when it comes to basketball sneakers specifically, I’m not sure he’s actually forgotten a thing.

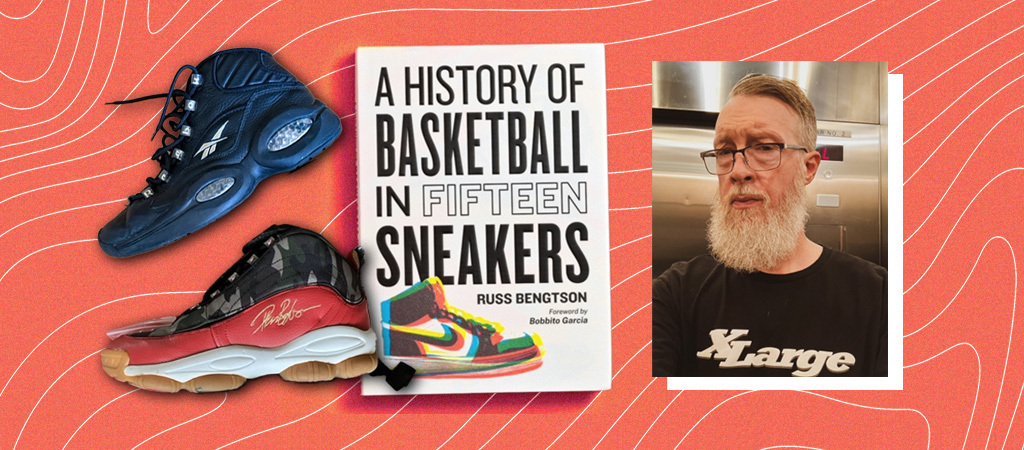

From his time as editor in chief at SLAM to stints with Complex and Mass Appeal, Bengtson has spent close to three decades professionally immersed in sneaker culture. That immersion goes back to childhood, and it’s inseparable from his love of basketball. His unparalleled insight on these parallel themes is on full display in his new book, A History of Basketball in Fifteen Sneakers (Hachette), which goes Marianas Trench-deep on how the game and its footwear have evolved from the no-tech days of Chucks and set shots to the colorful, high-tech products we wear and watch today. Extensively researched and loaded with interviews with players, designers, and industry insiders, it’s a goldmine for anyone who cares about hoops, kicks, and the colorful cultural spot where they intersect.

I caught up recently with Bengtson to talk about the book and his own history with basketball and sneakers. (Fullest possible disclosure: Russ is a friend, and the guy who hired me at SLAM back when he was EIC, so I can attest to his staggering knowledge of the subjects.)

I’m probably not the only one who said to you at some point that this is the book you were born to write, but in a way it really is. I think it’s fair to say that no one else has covered basketball and sneakers as long and as prominently as you have. Did you feel like you sort of had to do this?

To a degree. I would always go to Powell’s bookstore when I was in Portland, or go to the Strand (in New York City), and relentlessly go through their basketball books, looking for out-of-print stuff. I’ve really read all the basketball books I can find, and all the sneaker books I can find — some of which I contributed to — and there just was never enough crossover. There’d be a mention of some sneaker stuff in various basketball books, but it never really got that deep into it. And a lot of the sneaker ones would cover a ton of sneakers, but not really get as deep into basketball. And I go back to, when I first tried to get a job at SLAM, part of the reason was, I wanted those first series of Jordan re-issues that came out in like ’94 and ’95, and SLAM was pretty much the only publication that covered sneakers and basketball.

From the beginning, you were responding to the sneaker coverage as well as the basketball.

Yeah, but it goes back even further, and I talk about it in the introduction — I don’t really remember whether Jordan became my favorite player because of the shoes, or if the shoes came to my attention because of Jordan. The whole sneakers-basketball thing has been inseparable for me basically since I knew about either one. To me, it’s the separation that’s artificial. I think the real story to be told is them combined.

You and I are close to the same age, and looking back to that time, as a kid, I was a hoop fan much more than a sneakerhead — my sneaker ideal was like, the New Balance Worthys, because I was a huge Laker fan. So to me, you were an outlier back then, most kids didn’t really embrace the game and the sneakers that equally. Did you have that sense?

Maybe a little bit. I think a lot of people who were into sneakers back then were into the shoes just for the shoes. I was a big Jordan fan early on — I definitely had people write in my high school yearbook about Jordan.

So back to the book. What did you learn in the process of writing this that even you were like, Damn, I didn’t know that?

A bunch of things. One of the funniest was talking to Marques Johnson, who had one of the coolest jerseys ever when he

played for the Bucks — it had his full name across the back — and he played Raymond in White Men Can’t Jump, one of the greatest roles in a basketball movie ever. Marques was one of the ten players to wear the adidas Top 10. And he hated the Top 10, which is hilarious. He started talking about it, and you could feel him kind of going back and realizing how much visceral hatred he had for this shoe. That’s something I did not see coming.

Some of it was stuff I knew, but just a matter of perspective. To go back through some of the Air Jordan stuff, to talk to David Falk and Sonny Vaccaro, and it’s funny, I feel like both of them feel like the other gets too much credit (for Michael Jordan signing with Nike). And in talking to them, I think they’re both right. I think they misinterpret the others’ role, if that makes sense. Falk, I think, feels Sonny is trying to take the credit for getting Jordan to sign with Nike. I think what Sonny was able to do was convince Nike to go with Jordan. And even Falk knows Jordan’s success wasn’t super guaranteed. That’s still one of my favorite things: Nike signed him to a five-year deal and had an out that if he didn’t sell like a million dollars’ worth of Jordan stuff in three seasons, they could dump him for the last two years of the deal. And he sold $126 million in the first year. No one thought he would be a failure, but no one thought he would be that much of a success.

Other things… when I had initially proposed the book, I proposed the adidas Pro Model and the Superstar for the same chapter. I was like, “Well, the Superstar is just the low-top Pro Model. I can’t talk about one without the other.” What Chris Severn put me onto, as the guy who developed those shoes, was that it was the other way around — the Pro Model was the high-top Superstar. The first adidas basketball shoe was meant to be a low top. And I didn’t realize that Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, despite having a signature model through adidas, that was kind of just a commercial thing — something to sell with his name and face on it. He apparently wore the Superstar until ’87. He wore the Superstar after Run DMC kind of brought it back.

You talked to a ton of guys for this. Who were some of the more memorable conversations?

Kobe was amazing. We talked in late December, 2019. I’d known him since high school, met him at the McDonald’s All-American Game. His memory of all the shoe stuff was still super, super specific — he was a guy, obviously, it wasn’t just his name on it. Kobe, because we had so many conversations over the years, I kind of knew that he’d be great.

One thing I included in the proposal was the Boston Celtics wearing black shoes because Red Auerbach insisted on getting them because they would stay clean, they wouldn’t show dirt. Jeff Twiss, a long-time Celtics PR guy, got me on the phone with Tommy Heinsohn. Again, Tommy has since passed, but talking to him on the phone was just an amazing thing, you realize the entire NBA was within living memory. And he confirmed, the Celtics would issue you two pairs of Chucks at the start of the season, and if you wanted more than that, you would buy your own. And he would make two pairs of Chuck Taylors last the entire season.

Rick Barry, who was in the ads for the adidas Top 10 as the “inventor” of the shoe — I remember that ad from like Boys Life magazine when I was in Boy Scouts. He comes off as kind of a prickly dude, he definitely feels his own era should be appreciated more, and he has a lot to say about the modern game. Called him up one day, nicest guy in the world.

Jalen Rose was great, too. I never really thought about it, but a lot of those guys were from the Detroit area, so they weren’t exactly Jordan fans, because they grew up when Isiah Thomas was the king of Detroit. They weren’t even super Nike heads like that. Off the court, Jalen was talking about wearing Pumas, because that was the more Detroit thing.

Huge question I know, but how do you assess where basketball sneaker culture is now?

In a way I feel a little Cassandra-ish about this. There was a period where I wrote a sneaker column for Mass Appeal, and I remember writing about how I thought the bubble was going to pop. And this was probably 15 years ago. And the thing is, I think I was right, but what I didn’t anticipate was what was still then pretty much a subculture becoming this mass-market thing. And I think there was a long time where most people were content to just wear whatever — to go to Dick’s Sporting Goods or Kohl’s and buy whatever, and this whole other aspect that people who were into “sneaker culture” knew about didn’t affect them. Now, everyone knows about everything.

There’s a lot of “be careful what you wish for” in this. If you told me back in 1998 that I would be able to buy literally any Air Jordan from literally any era pretty much whenever I wanted, it would be like, “Wow, really? Sign me up.” But now, you look at the glory year Jordans, I to XIV, all of those became these iconic things. And people didn’t love all of them from the start, you know? Tinker (Hatfield, Jordan Brand designer) would talk about it — if people love it right from the start, you did something wrong. You need them to sort of grow to love it. And I think what retro did is make people impatient. If they don’t love something right away, they’ll just go buy the old thing, and a new release doesn’t really mean as much anymore. Before, you would buy the new Air Jordan because it was the new Air Jordan. You might have liked one prior to it more, but that one’s gone. And I think that’s true of pretty much anyone’s line now.

And from the basketball side — it’s funny, and I’m sure you notice this too: Back when we were going into locker rooms, we would pick what to wear to go to a game. If you could blow an NBA player’s mind with a pair of shoes, the streets didn’t have a chance. I distinctly remember, we would pass out issues of the magazine, and I would give one to, like, Tim Hardaway, and he would flip straight back to the sneakers before he looked at anything else. Tim Hardaway was on Nike! He had his own shoe! But he still wanted to see what was coming. So players back then were into it, but I think with the uniform rules and there not being as much of a viable selection of what to play in…

Right, it was pretty limited what color options the NBA would allow.

And now, everything’s wide open. And again, it’s kind of, be careful what you wish for. Formerly, the All-Star Game, people would wear crazy stuff. Finals, maybe, things would get a little more open. Now, it’s just like every game is an All-Star Game. There’s no rules anymore. I look at that Kobe Grinch shoe, which people were psyched on because Kobe wore it once on Christmas Day, and then I think last Christmas or two Christmases ago, it got retroed, and a bunch of guys wore it on Christmas. And I swear, at least one player has worn it in an NBA game pretty much every day since. I feel like that makes it less special. There’s something to the idea of a one-and-done, or a shoe being available for a season and going away and being replaced by something new.

I look at LaMelo, Jayson Tatum, even Steph to an extent. Luka, Giannis, Scoot. I feel like that stuff is kind of a light at the end of the retro tunnel. Retro’s only been a thing for like 25 years. If you look at kids, I think a lot of kids are wearing signature stuff from players they like. I look at some of those shoes, and I forget — and I’m sure other people our age forget — this stuff isn’t really for us. It should be what kids in high school like now. I don’t think people our age should be dictating what’s cool to kids who are 15. They don’t remember Michael Jordan as a player.

There are kids now who don’t realize Michael Jordan was a basketball player. It’s not even that they don’t remember him, they just think of him as a brand in the same way that Chuck Taylor is a brand. Which is insane to us, but…

Right. Part of the reason I wanted Bobbito (Garcia) to write the forward to this, I look at his book (Where’d You Get Those? New York City’s Sneaker Culture: 1960-1987) as being kind of a companion, almost. Obviously, his is through the filter of New York, and mine is through the filter of basketball as a whole. He looked at the Air Jordan I as being kind of the end. And for me that was the beginning, especially being in the suburbs. But over the years, I’ve come to see his perspective, where it’s like, if you’re someone who has to determine on their own what cool is, and all of a sudden you see a brand pushing something to be cool and people just accepting it, it’s like, wait a minute, that’s supposed to be our job. It’s kind of the same way I see it now, people need to take that power back from brands, instead of just chasing whatever the latest hyped retro is.

We went to a bunch of basketball courts in New York on the day the book was published to hand copies out, and me being me, I was like, “What do I wear?” I thought about it for a while beforehand, and I was like, actually, I need to put my money where my mouth is and wear a pair of current basketball shoes. I’ve been meaning to buy a pair of Tatums for a while now, or a pair of Ja Morants, and I ended up going to Dick’s Sporting Goods — that’s another thing with me, I don’t want to buy a new model that I’ve never tried on before. I ended up getting the black and gray Tatums, wore them all day.

So we hit all these courts, and on the way home, back on Long Island, I wanted to stop at Barnes & Noble and see if the book’s there, because I hadn’t seen it on a shelf yet. So I go in, and find it. Then I go over to the music side, and there’s this dude on the same aisle, he looks down and he goes, “Yo, those shoes are hard. What are those?” He thought they were Kyries, and I’m like, “Nah, they’re Tatums.” And that’s the thing, if you buy a new performance shoe or new signature shoe, you win twice. A, they’re readily available for the most part, and B, if you wear them, people probably aren’t going to know what they are. If you get the newest, craziest retro, spend like five grand on it, people are going to be like, “Oh my god you have those,” but they know what they are. Personally, I think it’s much cooler to buy some new stuff that you like and wear that instead.