If you’re a big bock beer fan, you’ve probably noticed that at least a few cans you imbibe regularly are adorned with the image of a goat. Have you ever wondered why this is? The story of the goat goes all the way back to the 1400s in the northern German city of Einbeck. This is where bock beer began.

In the 1600s, the style made its way south to the Bavarian region and, because of a dialectical error, locals began referring to the beer as “Einbock” or “a goat” instead of Einbeck. That’s why today, some four-hundred or so years later we still find bottles and cans featuring a goat.

Why this beer style is great for spring imbibing is a different story altogether. Traditionally, monks brewed the malty, heavier bock style during the winter months to drink during their Lenten fasting.

Regardless of whether or not you noticed the goat mascot or you plan to fast during Lent, you can still probably understand the appeal of bock beer during the spring months. So can brewers. That’s why we asked a few of our favorite brewers, craft beer experts, and beer professionals to tell us their favorite bock beers to drink this season. Keep reading to see all of their picks.

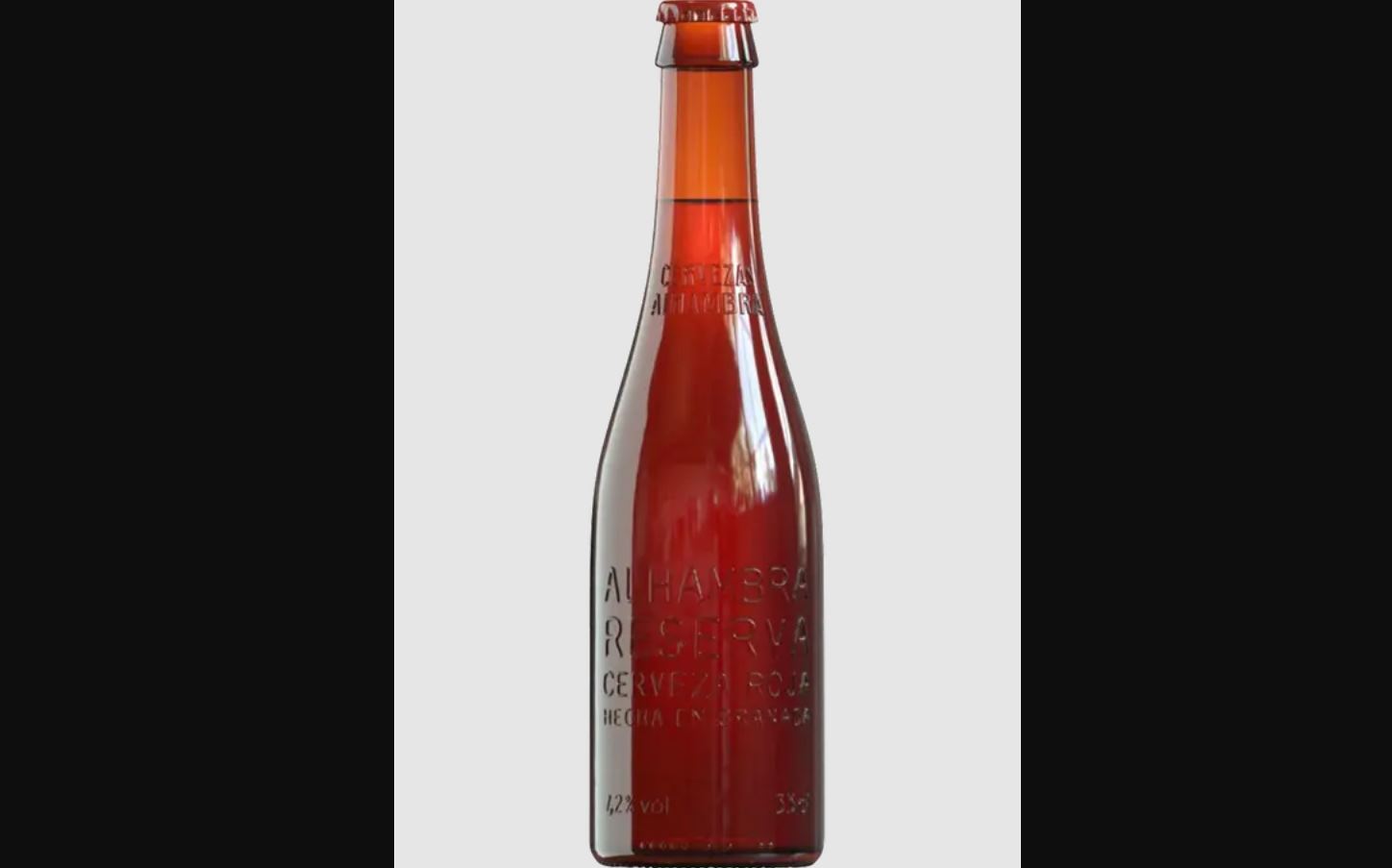

Alhambra Reserva Roja

Zach Fowle, head of marketing for Arizona Wilderness Brewing Co. in Phoenix

ABV: 7.2%

Average Price: $11 for a four-pack

The Beer:

Alhambra Reserva Roja. Normally, to encounter a bock this close to the style’s ideal you’d have to travel to Northern Germany. Granada, Spain (where Alhambra, a subsidiary of Madrid’s Mahou San Miguel since 2007, is located) is a slightly shorter trip, but thankfully this beer’s also distributed in the US.

Tasting Notes:

Take a sip and you get deeply toasted bread crust, moist raisin bread, and a hint of sassafras root; a thick, chewy body and balanced, medium-dry finish; and a mild but lingering tree-bark bitterness with just a nudge of alcohol warmth.

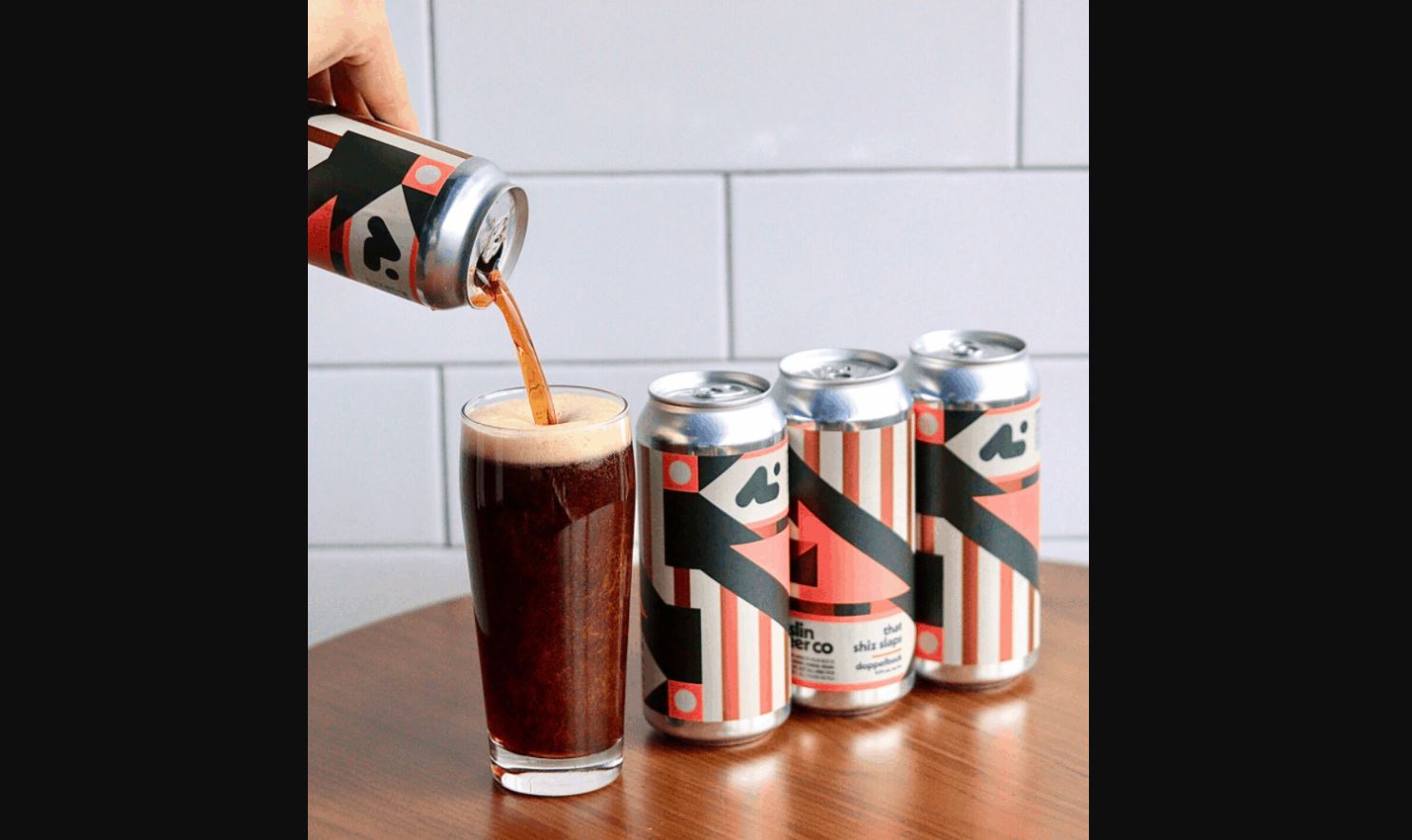

Aslin That Shiz Slaps!

Garth E. Beyer, certified Cicerone® and owner and founder of Garth’s Brew Bar in Madison, Wisconsin

ABV: 9.5%

Average Price: $12 for a four-pack of 16-ounce cans

The Beer:

That Shiz Slaps! from Aslin is a doppelbock that’s well-suited for spring drinking. It’s a meal in a can. The ABV is a bit sneaky, so watch out.

Tasting Notes:

It really leans into the dark fruit notes of prunes and fig and raisin jam on toasted bread.

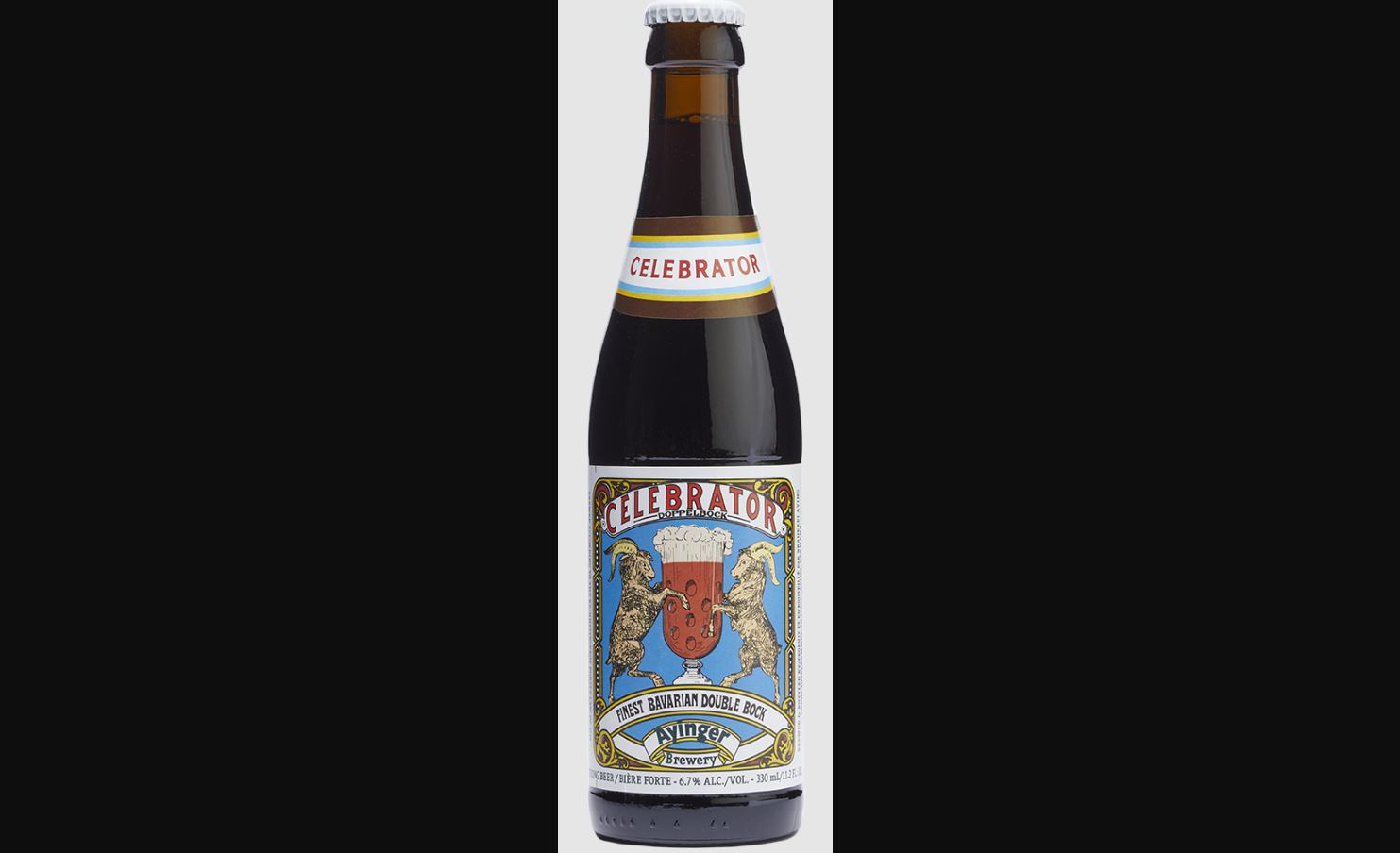

Ayinger Celebrator

Charlotte Herndon, taproom and events manager at Exhibit ‘A’ Brewing in Framingham, Massachusetts

ABV: 6.7%

Average Price: $13 for a four-pack of 16-ounce bottles

The Beer:

Celebrator by Ayinger Privatbrauerei, a 6.7% doppelbock, is a long-time classic. It’s an award-winning beer for good reason. It is a beer I can return to time and time again and still appreciate the profile it has to offer me. This beer has lasted a long time because it is one you don’t grow tired of.

Tasting Notes:

It has the rich malt profile I search for in a bock without too much heaviness in its body. It delivers a rich malt with just a touch of sweetness on the finish to cut the coffee tones on the backend.

Andechs Doppelbock Dunkel

Ryan Pachmayer, head brewer at Yak & Yeti Brewpub and Restaurant in Arvada, Colorado

ABV: 7.1%

Average Price: $4 for a 16.9-ounce bottle

The Beer:

When visiting Germany last year, a fresh liter of Doppelbock Dunkel in the beer garden at the hilltop monastery Klosterbrauerei Andechs was quite special. It wasn’t quite winter bock season in Franconia, but I enjoyed a very good one from Fassla in Bamberg as well.

Tasting Notes:

Classic flavors like brown bread, toasted malts, dried fruits, caramel, toffee, and lightly herbal, floral hops make for an exceptional beer to drink this season (and any season).

Huber Bock

Ryan Schmiege, brew master at Cascade Lakes Brewing Company in Redmond, Oregon

ABV: 5.5%

Average Price: $12 for a twelve-pack

The Beer:

Huber Bock from Minhas is my pick because it brings me great memories of my college years. It’s a classic, clean, no-frills bock beer for any occasion. It’s a smooth, crushable, classic.

Tasting Notes:

Huber Bock is an easy-drinking lager featuring very light coffee elements and roast character with an appropriately balanced hop presence.

Schneider Weisse Hopfenweisse

Parker Penley, lead innovation brewer at Widmer Brothers in Portland, Oregon

ABV: 8.2%

Average Price: $6 for a 16.9-ounce bottle

The Beer:

Schneider Weisse makes a great Weizenbock called Hopfenweisse. It’s never totally fresh in the States in the bottle so I can only recommend you have it fresh at the brewery in Munich. It goes down so easily and is absolutely delicious.

Tasting Notes:

A great choice for spring drinking, this Weizenbock shines with flavors like banana, clove, dried fruits, and floral Noble hops.

Grieskirchner OsterBock

Dominique Trolliet, brewer at Wynwood Brewing Co. in Miami

ABV: 7.1%

Average Price: Limited Availability

The Beer:

Well, on the way to Munich last year via Vienna, I had a bock by Grieskirchner that was perfect. I suspect it is the result of years of brewing, the water source that must be just right. Centuries of brewing deliver the perfect glass of beer.

Tasting Notes:

The malt, the roast, the balance of malt and hop, the smoothness of the beer, and the impressive foam retention.

Sierra Nevada Beer Camp Weizenbock

Josh Bartlett, founder of Learning to Homebrew in Tuscaloosa, Alabama

ABV: 7.9%

Average Price: Limited Availability

The Beer:

Dating back to Medieval Germany, bocks are steeped in history and encompass a wide variety of substyles such as the Helles Bock or the Doppelbock. One of my favorite styles is the only non-lager bock in the family, the Weizenbock. One of the best is Sierra Nevada Weizenbock, released in its Beer Camp series.

Tasting Notes:

Tricky to find in a bottle, Sierra Nevada’s Weizenbock includes flavors of malty vanilla custard, banana, and clove along with a rich, creamy mouthfeel.

Paulaner Salvator

George Hummel, grain master of My Local Brew Works in Philadelphia

ABV: 7.9%

Average Price: $11 for a six-pack

The Beer:

When it comes to a classic European style, I think it’s always best to take it back to the roots. Let’s face it Salvator by Paulaner in Munich, is the beer all those other bock beers want to be. Truly the liquid bread of German monks.

Tasting Notes:

It’s thick and sweet. With notes of caramel, milk chocolate, and honey. A glass of Salvator alongside a sandwich of Westphalian ham, Bruder basil cheese, and mustard on pumpernickel. Yum.

Schilling Brücius

Frederic Yarm, USBG bartender in Boston

ABV: 6.9%

Average Price: $8 for a 16-ounce can

The Beer:

Schilling’s Brücius is a delicious doppelbock with a complex offering of burnt sugar, nutty, milk chocolate, toasted bread, and grassy notes.

Tasting Notes:

Its richness and body are quite satisfying in the colder months and into Spring.

: Live on the NBA App

: Live on the NBA App