The Rundown is a weekly column that highlights some of the biggest, weirdest, and most notable events of the week in entertainment. The number of items could vary, as could the subject matter. It will not always make a ton of sense. Some items might not even be about entertainment, to be honest, or from this week. The important thing is that it’s Friday, and we are here to have some fun.

ITEM NUMBER ONE — Show me my favorite characters as babies, see what I care

It looks like origin stories are here to stay. At least for a while. It’s a whole thing now, especially this week, with Emma Stone’s Cruella hitting theaters and streaming this weekend and Timothee Chalamet signing on for an upcoming one about Willy Wonka. But it’s been going on for a while now. There was a gritty Scrooge origin story on television not long ago. The X-Men franchise seems to re-tell its origin story every three or four movies. Again, it’s a whole thing. A Black Panther origin story series for Disney+ was just announced last night.

The temptation here is to get cranky about it, to decry the mining of intellectual property in such a blatant way, to raise your fist to the heavens and shout “Was it not enough? Were the reboots and sequels and extended universes not enough? How far does it go? Where does the madness end?” in the general direction of the movie gods. And I get that. I do. Not everything needs a full-length origin story. I kind of like the idea that Willy Wonka is just some fully-formed kooky candy man. I do not necessarily want to know what trauma caused him to become that way. It seems like something that will make me sad.

But shouting at the clouds won’t make them go away, even if you shout very loud. (I’ve tried.) And so, I have decided to just lean all the way in. Screw it. Give everyone an origin story. Give origin stories their own origin stories. Show me what Thanos was like as a teenager. Give me a very small John Wick flinging building blocks at people in a nursery school. Skip right over the Batman origin story and just show me how Thomas Wayne got so rich. Don’t even put supervillains in it. Just make it Billions but with Batman’s dad. I am barely joking.

The truth is, origin stories can be pretty cool when they’re done well. The Godfather Part II was basically an origin story, at least in De Niro’s half. Better Call Saul is an origin story and it rules, which is really wild when you think about it. They took the comic relief from Breaking Bad and gave him a huge dramatic backstory about sibling rivalries and inferiority complexes and all of it. There might be no better proof that these can work than that. I hope they keep going backwards. Do the next show about Lalo Salamanca’s rise to power. Now I am not joking at all.

The cynical ones aren’t as fun, sure. You know those when you see them. But there are uglier cash grabs out there, lots of them. At least origin stories attempt to add context to things, to show you why and how compelling characters became that way. And if the origin story trend keeps cooking and growing and it all ends up with me in a theater watching a toddler Dominic Toretto ripping around the parking lot of his daycare in a NoS-fueled Power Wheels in a Muppet Babies-inspired Fast & Furious movie, well, I guess there are worse ways to spend two hours.

ITEM NUMBER TWO — “I don’t read scripts, I smoke pot”

Background will help, I suppose, but only a little, because the quote in this heading is incredible and we can’t go around wasting time when there’s important business to like that get to. Here goes: Former O.C. star Rachel Bilson is now doing a podcast about the show, kind of a rewatch/behind-the-scenes thing, where she has former co-stars and notable figures swing by and chat the show that burned fast and bright across the early 2000s pop culture sky, like a meteor with a pastel popper collar on.

This week, the guest was Tate Donovan, who played noted fraud aficionado Jimmy Cooper on the show and later went on to direct a few episodes. That’s what we’re discussing here, his directing. And specifically, the time he tried to give Bilson a note about a scene. He prefaced it all with some kind words about how the teen actors on the show were all fried and ready to bail and everything was wearing thin, which was nice and fair of him to do. And then this happened.

“So, I just wanted to put something in your mind. And I said … ‘Just so you know, that was great. Just so know, you’ve just come from Seth’s room, and you’ve had a huge argument, in that thing, and you’re like, breaking up. And so, I want to see that argument in you … You know that right? You know that you had an argument with Seth?’” Donovan continued. “I didn’t want to step on toes. I didn’t want to insult you by reminding you of that.”

It was at that point that Bilson chimed in, “I think I know where this is going.”

As Donovan carried on, he revealed Bilson had an unusual reply — one he calls one of the “best quotes” he’s heard from an actress in his life.

“You go, ‘Tate, I don’t read scripts, I smoke pot,’” he said to laughs from the actresses and podcasters.

This is… the coolest thing I’ve ever heard? I don’t know. I don’t know. It’s definitely close. At the very least it is right up there near the top with the time someone asked Allen Iverson why he didn’t lift weight and he replied “That shit was too heavy.”

Iverson just said he didn’t lift weights when he played because “that shit was too heavy.”

— Derek Bodner (@DerekBodnerNBA) December 17, 2016

I mean, come on. “I don’t read scripts, I smoke pot.” I can already tell that this is one of those sentences that will live in my brain forever. I’ll be on my deathbed hopefully many decades from now and the only things left in my head will be this, the Iverson quote, and the thing where Liam Gallagher says he owns 2,000 tambourines. Have Iverson and Liam on the O.C. podcast next. I doubt very much that either of them have seen a single episode and I do not care at all.

ITEM NUMBER THREE — Eternals looks wild as hell

The tricky thing here is that I am bad at the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Always have been. I’ve pieced it together as I’ve gone along and I do find myself rewatching some of its individual movies quite a bit (Ragnarok and Black Panther, hello), but as far as knowing the lore and the chronology of events and remembering every lesser hero… not so much.

That doesn’t mean I don’t or can’t enjoy the whole thing. As we discussed just last week, I did not know who Kite Man was and how he related to the world of Batman before I started watching Harley Quinn, and now I worry about him constantly and want him to be happy. Point being: This is the trailer for the next film in the MCU, Eternals, directed by Nomadland’s Chloe Zhou. It looks super cool. Also, I do not know who anyone is or why they’re there or how it all ties into the events of Endgame, which I do not entirely remember.

Maybe I should read the description. Maybe that will help.

After an unexpected tragedy following the events of Avengers: Endgame, the Eternals — an immortal alien race created by the Celestials who have secretly lived on Earth for over 7,000 years — reunite to protect humanity from their evil counterparts, the Deviants.

Hmm. Nope. No dice.

I guess this is one of those Two Things Can Be True At Once situations. The first is that it appears I will never be able to keep all of the information in the MCU in my head. This is not a comment on the quality of the project. Lord knows I am not trying to say I’m above it. It’s just clear at this point that I’m going to be a little lost, and that’s okay.

The second thing is that Eternals looks cool as hell and it’s cool that Marvel keeps handing big projects — again, Ragnarok, Black Panther — over to smart directors who have things to say about the characters. I will see this movie. I’ll spend the first 30-40 minutes confused, I bet. But I can deal.

ITEM NUMBER FOUR — Let’s check in with Quincy Jones

Hey, let’s see what iconic producer and music legend Quincy Jones is up to these d-… aaaaaaand he’s giving a series of outrageous quotes to an interviewer. Again. Here, look at this, from The Hollywood Reporter.

Did you know Judy Garland at all?

I worked with her at Newport [Jazz Festival]. You kidding? I’d never forget that. We were playing the evening show with Duke Ellington, and she came out and the wind was in the mic, so Phil Ramone, the engineer, came out and put a condom on the microphone. To keep the wind away. And when Judy came out, she did like this. (Mouths swallowing the mic.) I never let her forget it.

Bless this man. He has eight decades of the greatest stories you’ve ever heard and he will be goddamned if he doesn’t share them with anyone who wants to know. The man simply cannot keep secrets. It’s great. I want him to start a podcast. Just call it “Quincy Talks His Shit” and have listeners write in with questions — or, hell, just the name of a famous person or event — and let him go until he is out of things to say. I would listen every week.

Now, I hear you. You’re saying, “I don’t know, Brian. This all seems like you reaching for an excuse to post his quote about the Beatles from that Vulture interview a few years back. Is that what is happening here?”

Hmm. Sure is!

That they were the worst musicians in the world. They were no-playing motherfuckers. Paul was the worst bass player I ever heard. And Ringo? Don’t even talk about it. I remember once we were in the studio with George Martin, and Ringo had taken three hours for a four-bar thing he was trying to fix on a song. He couldn’t get it. We said, “Mate, why don’t you get some lager and lime, some shepherd’s pie, and take an hour-and-a-half and relax a little bit.” So he did, and we called Ronnie Verrell, a jazz drummer. Ronnie came in for 15 minutes and tore it up. Ringo comes back and says, “George, can you play it back for me one more time?” So George did, and Ringo says, “That didn’t sound so bad.” And I said, “Yeah, motherfucker because it ain’t you.” Great guy, though.

“Great guy, though.” Makes me laugh every single time. Let’s keep Quincy talking straight through summer. The people deserve this.

ITEM NUMBER FIVE — Forget it, Jake, it’s Penguin Town

This is the trailer for an upcoming Netflix docuseries called Penguin Town. It is maybe the cutest shit I have ever seen in my entire life. Look at those freakin’ guys! They keep wobbling and stumbling! Look at them!

There is, I should report, more to this series than klutzy penguins, although I would absolutely watch a feature-length documentary titled Klutzy Penguins. It is narrated by Patton Oswalt and sounds kind of interesting. Per Netflix.

You’ve never met penguins like these before. Forget ice and snow, this rowdy colony of African penguins are hitting the sun-drenched beaches and breaking all the rules. Filled with boisterous shenanigans and loads of adorable penguins, this eight-part series from Red Rock Films about the real lives of African penguins brings flipper-flapping fun and drama. Join the ride … this town is gonna get painted black and white!

So there’s that. Which is cool. I suppose you have to fill all the hours with something. But even if it just ends up being like multiple hours of this…

… I am extremely in. I’m not a complicated man. I like movies about assassins coming out of retirement to murder hundreds of their enemies in the most violent ways possible and I like cute penguins doing adorable stuff in slow motion. That’s all.

ITEM NUMBER SIX — PERD

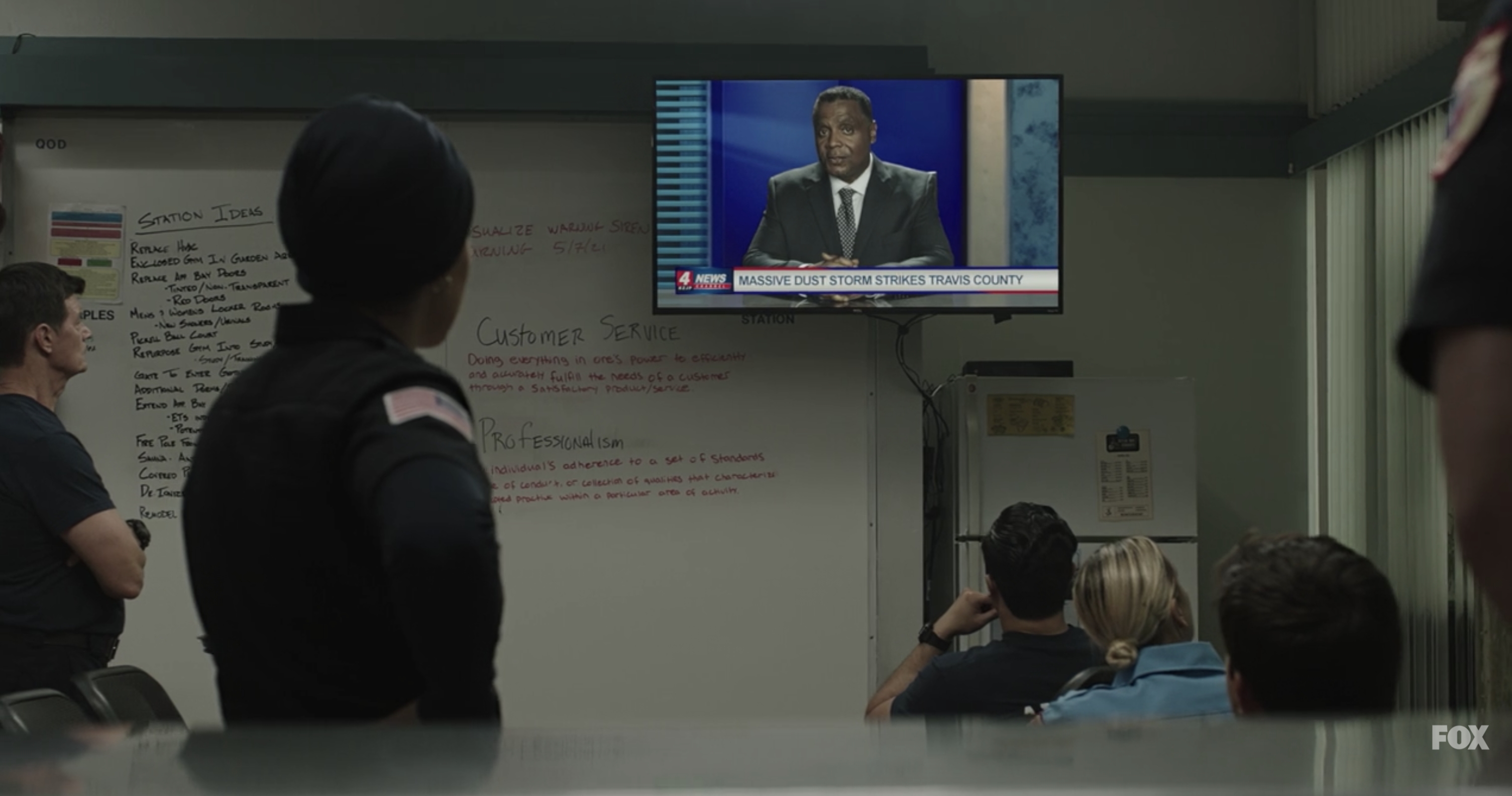

The season finale of 911 Lonestar aired this week. There was a huge dust storm and dramatic events and Texas was just generally in peril. It’s a lovely show. More importantly, look at that screencap. Look up in the corner. In the television. Do you see it?

Enhance.

ENHANCE.

PERD.

Yes, there is Jay Jackson, best known for playing Perd Hapley on Parks and Recreation, appearing as a news reporter and/or anchor, yet again. I know I just wrote about him a few weeks ago when he popped up in the background of Without Remorse. I do not care. This is like my favorite thing now. I am going to point it out every time I see it. It could be a lot. The man is a treasure.

READER MAIL

If you have questions about television, movies, food, local news, weather, or whatever you want, shoot them to me on Twitter or at [email protected] (put “RUNDOWN” in the subject line). I am the first writer to ever answer reader mail in a column. Do not look up this last part.

From Kate:

I just read in a magazine that Guy Fieri and Matthew McConaughey are friends, and this is amazing. Like, what an iconic friendship. I think they should host a cooking show together— they could call it “Matthew McConaughey’s Meals” or something and Guy could abbreviate it “Triple M” like he does with Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives. I mean, Guy could make a meatball sandwich or something and then Matthew McConaughey would be like “Alright, alright, alright.” So, my question for you is if you could have any celebrity or pair of celebrities host a cooking show, what would it be called? What would be their specialty dish?

See, this is a good email, for a bunch of reasons. It states a fun fact, that Matthew McConaughey and Guy Fieri are friends. It allows me to link to this Forbes report about Guy’s new Food Network deal being for $80 million over three years, which is somehow both more and less than I expected it to be. And it gives me an excuse to remind you that Matthew McConaughey gave a speech at Guy Fieri’s Walk of Fame ceremony when he got his star. Look at these two jokers.

And best of all, it sets me up to give a completely unhinged answer to a fun question. Who WOULDN’T I want to see host a cooking show, Kate? There are so many options. And I don’t even have to make-up “Snoop Dogg and Martha Stewart” because that sucker already exists, somehow.

Let’s see, let’s see. Hmm. I could go a lot of ways here. I’m tempted to go for pure chaos and just say I want a Tracy Morgan cooking show, but that feels like cheating because the Guy/Matt pairing includes one legit food-related personality. We need to ground this in reality, at least a little.

But this is a blessing in disguise, really, because now I get to type this collection of words: A cooking show hosted by Tracy Morgan and Barefoot Contessa Ina Garten. It would be called Getting The Oven Pregnant, in honor of Tracy, and their signature dish would be… oh, let’s go with shark stew. Also in honor of Tracy. Because of this, one of the greatest television lines in history.

This was a good email. The only downside is that now I really want to see this show.

AND NOW, THE NEWS

To Wisconsin!

An alligator is missing in Shawano County.

It’s from Doc’s Zoo at Doc’s Harley Davidson along Highway 29 in Bonduel.

Just to be clear here, because I think that’s important: What we have so far is an alligator escaping from a zoo in Wisconsin that appears to be either inside or adjacent to a Harley Davidson dealership owned by a man named Doc. Please do not correct me if any of this is wrong. I need this.

“We came out to feed the gators today and one of them was missing,” said Hopkins. “There was no sign of the enclosure being breached in any way or the gator digging underneath or anything. It’s just very strange. This has never happened before.”

I mean, if you can’t trust the security measures of a zoo located on the same plot of land as an establishment that sells motorcycles…

So this is all quite fun, really. But there’s still an alligator on the loose. There’s an element of danger involved. Because alligators are predators and without a source of food, this one could get hungry and become a danger to children and pets in the area. Unless…

“The old gator is very unathletic and quite overweight,” said Hopkins. “He can barely open his jaws. He has terrible arthritis in his jaws. If he can open up his jaw an inch and a half, it’s a lot….The most he could do is probably slap you with his tail and that is only if you get close and upset him.”

Well, guess what: I love this guy. I love this gator. I hope he told all the other animals in the motorcycle zoo that he was gonna bust out and I hope all of them were like “Pfft, you’re not going anyway, Dave,” and then I hope they all woke up the next day like, “Wow, Dave really did it.” If there’s any justice in this world, my dude is sipping umbrella drinks on a beach somewhere, happy, free. Good for him.

JUDAS

JUDAS

(@lunaenbyjazan)

(@lunaenbyjazan)

(@kingdj_5297)

(@kingdj_5297)  (@dominiquemoon_)

(@dominiquemoon_)

(@KevinlyFather)

(@KevinlyFather)